Korean artist Ik-Joong Kang on the art of being Zen – interview

Posted on 02/05/2014 by Art Radar

Christine Lee

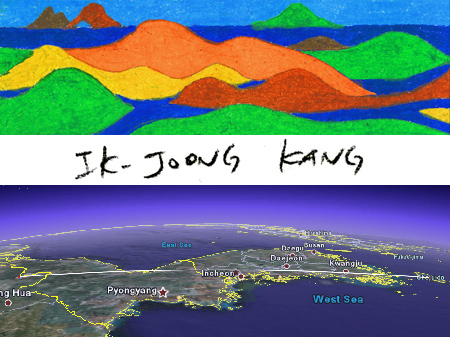

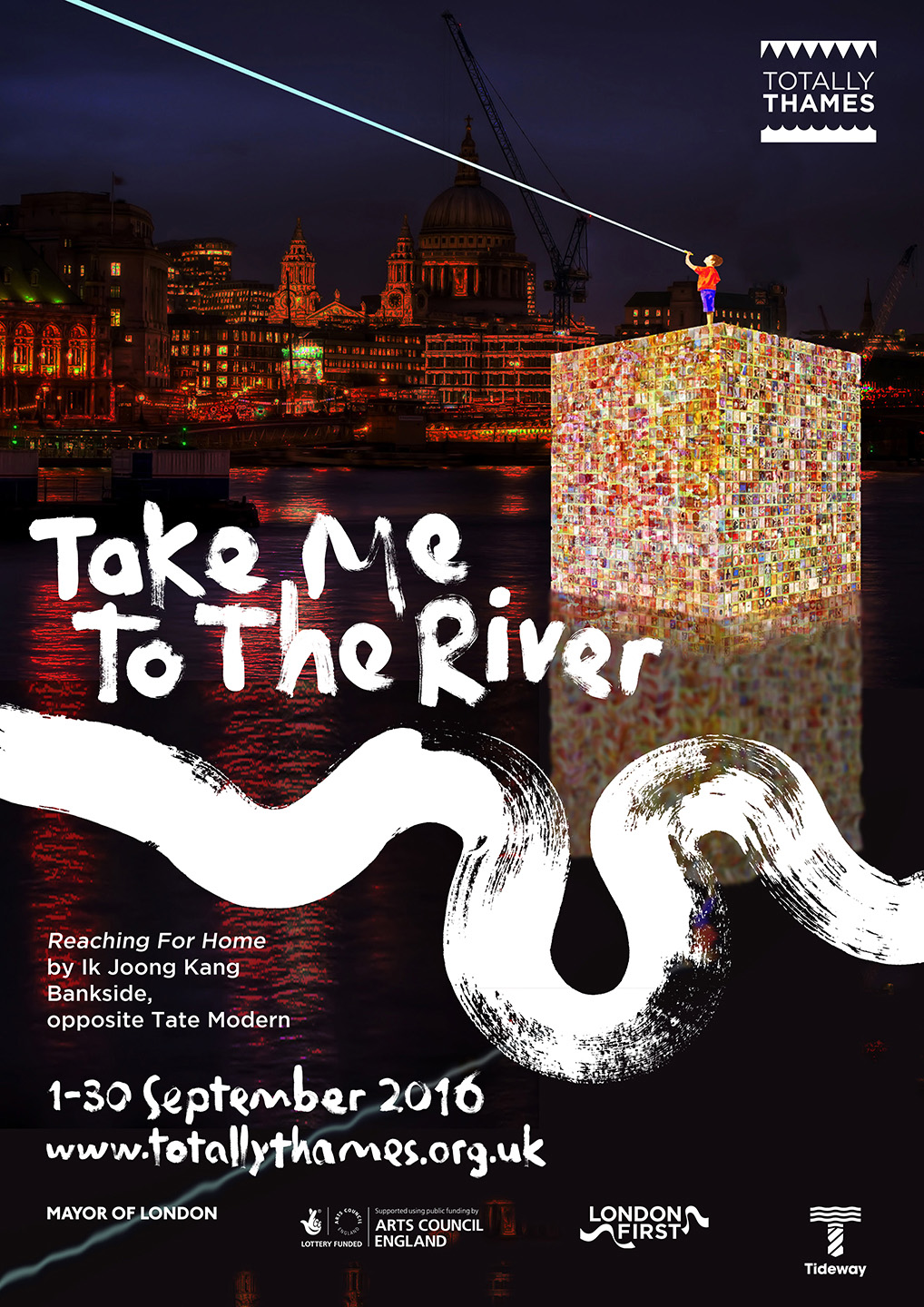

Korea’s Ik-Joong Kang speaks to Art Radar about his artistic influences, his hope for reunification of the two Koreas and why people are the most exciting artistic medium of all.

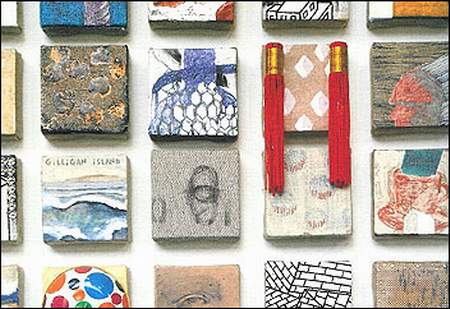

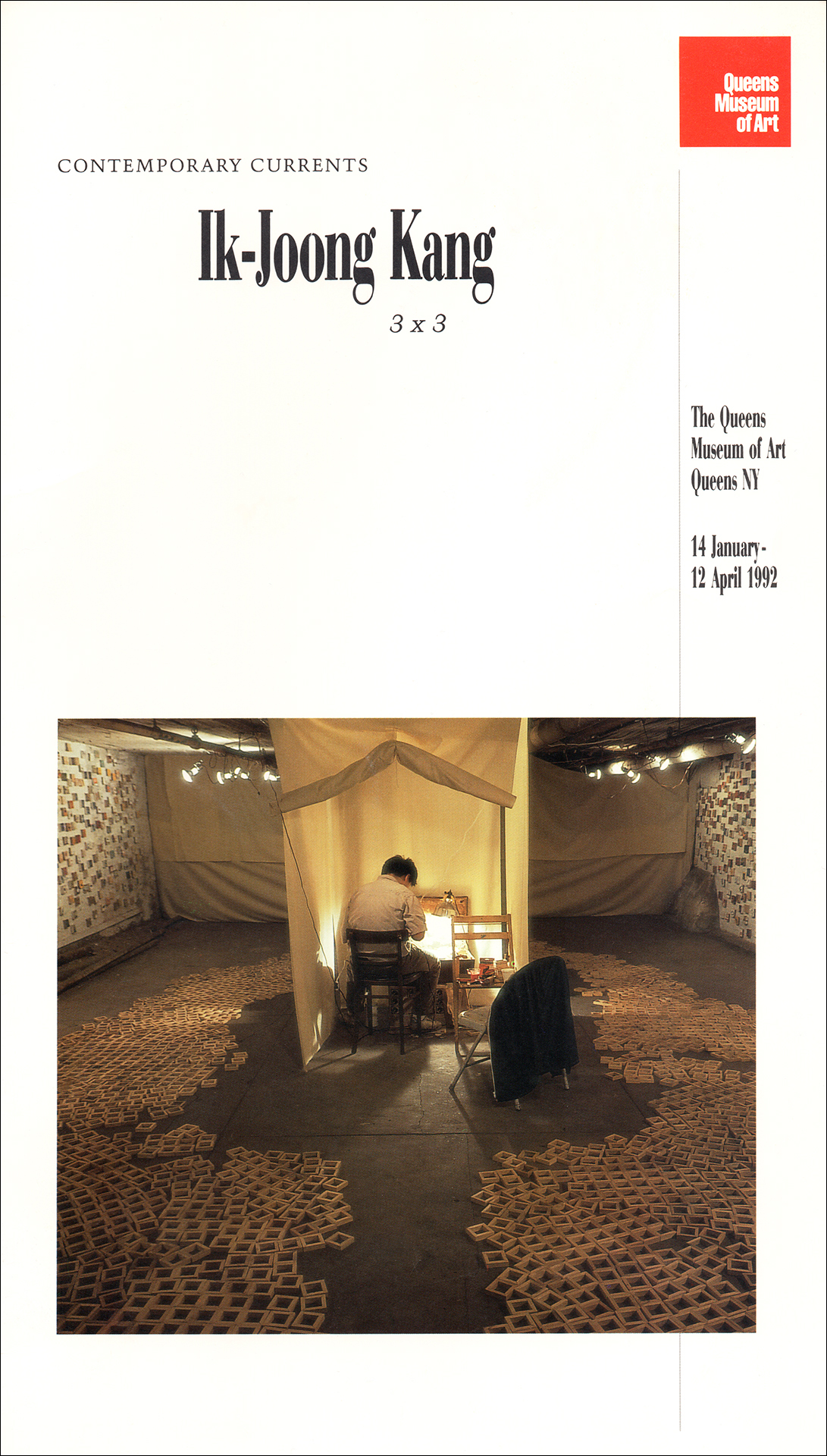

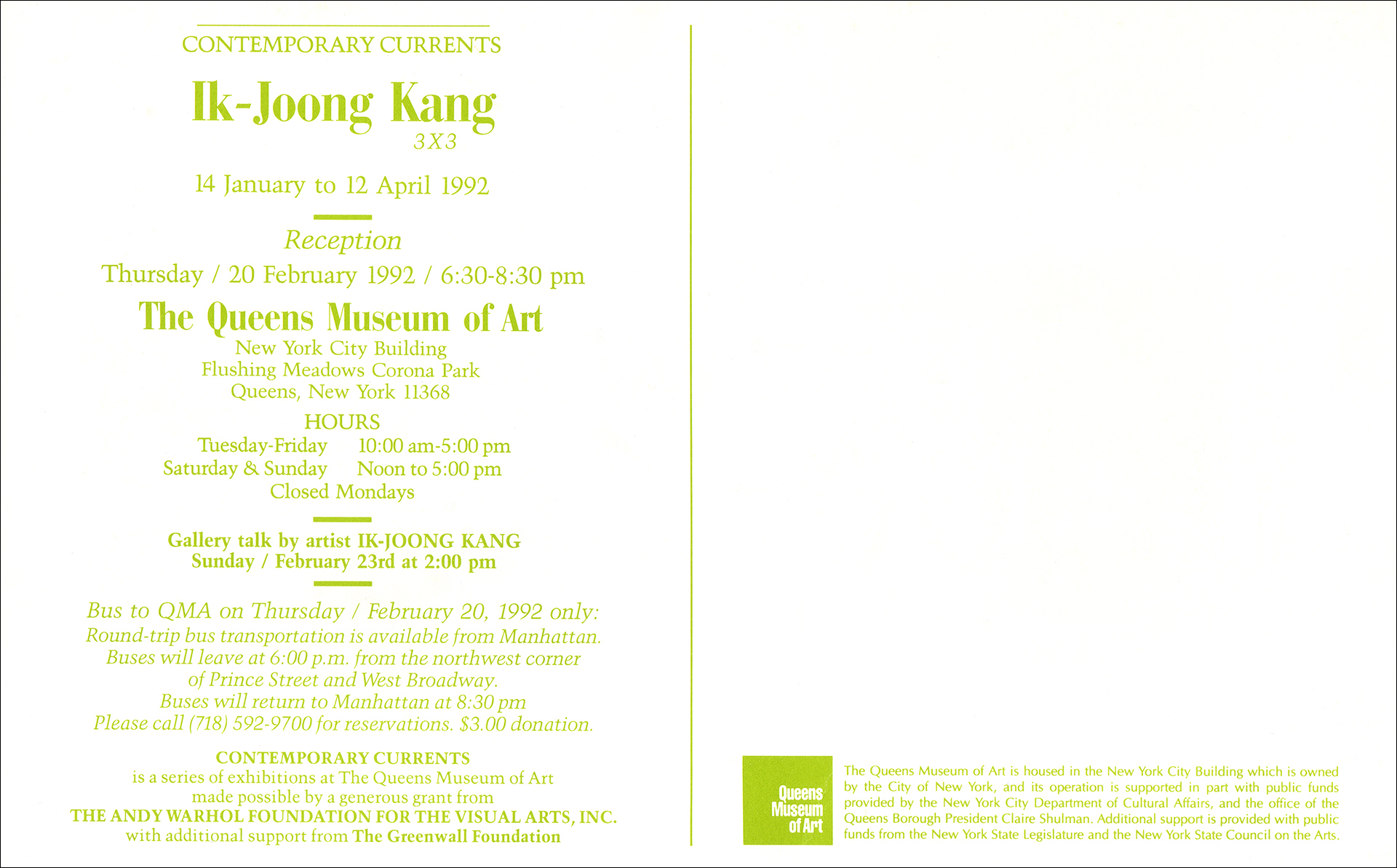

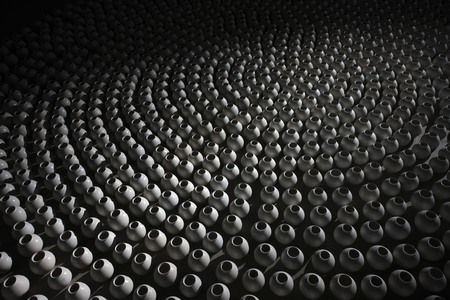

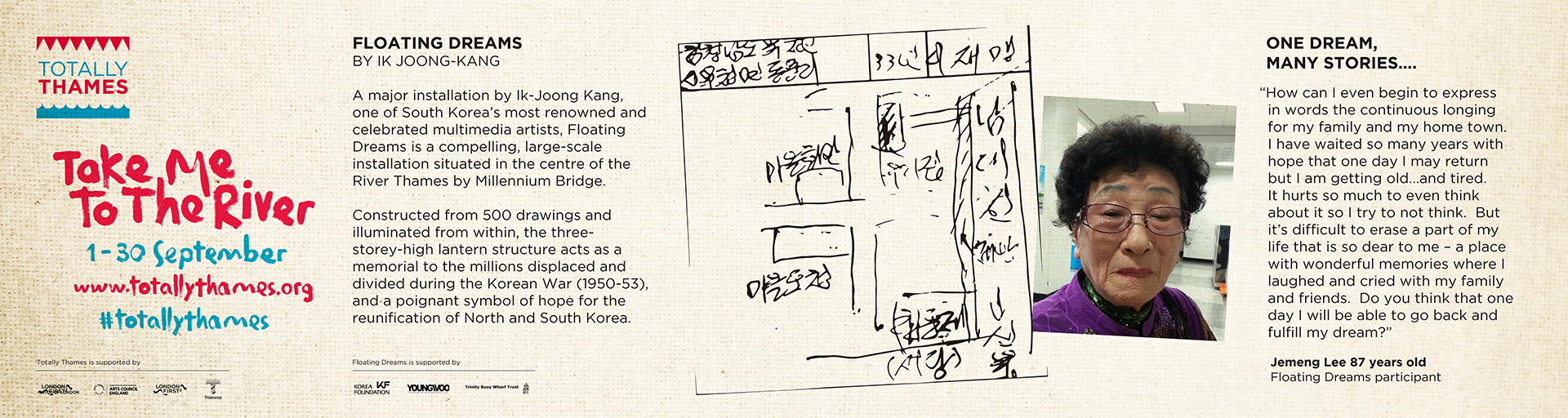

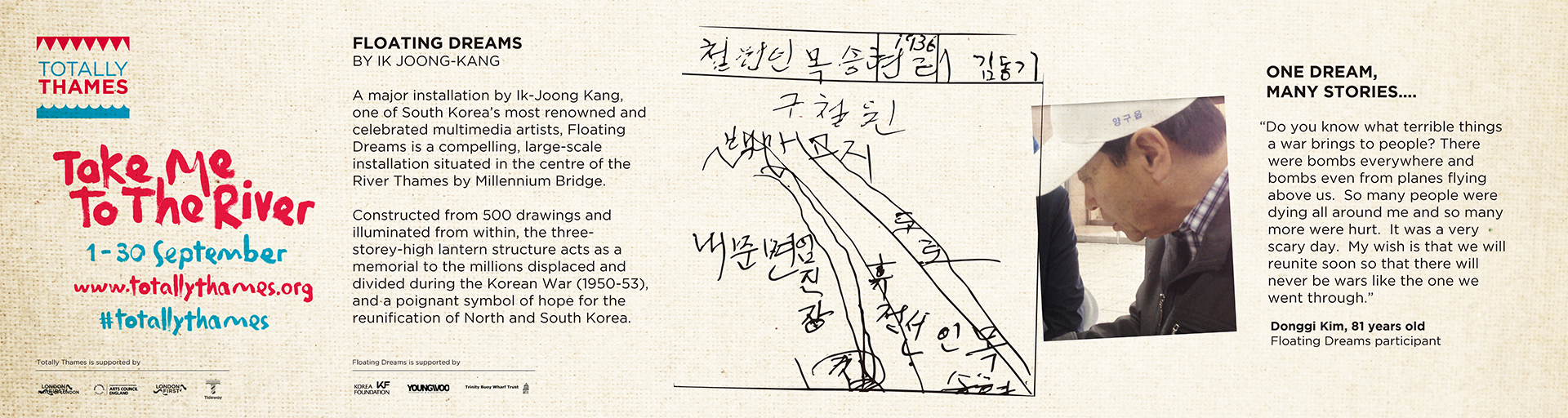

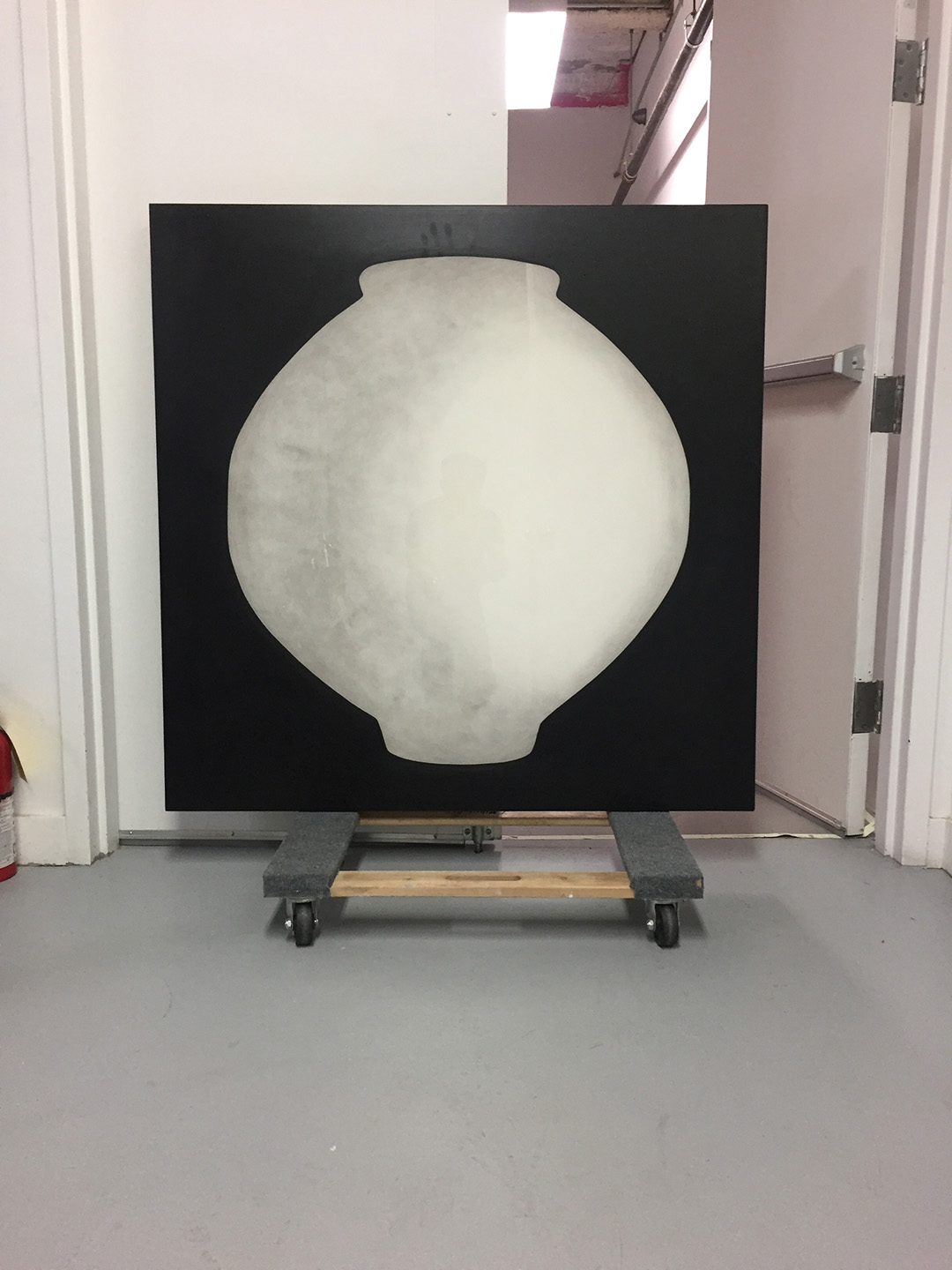

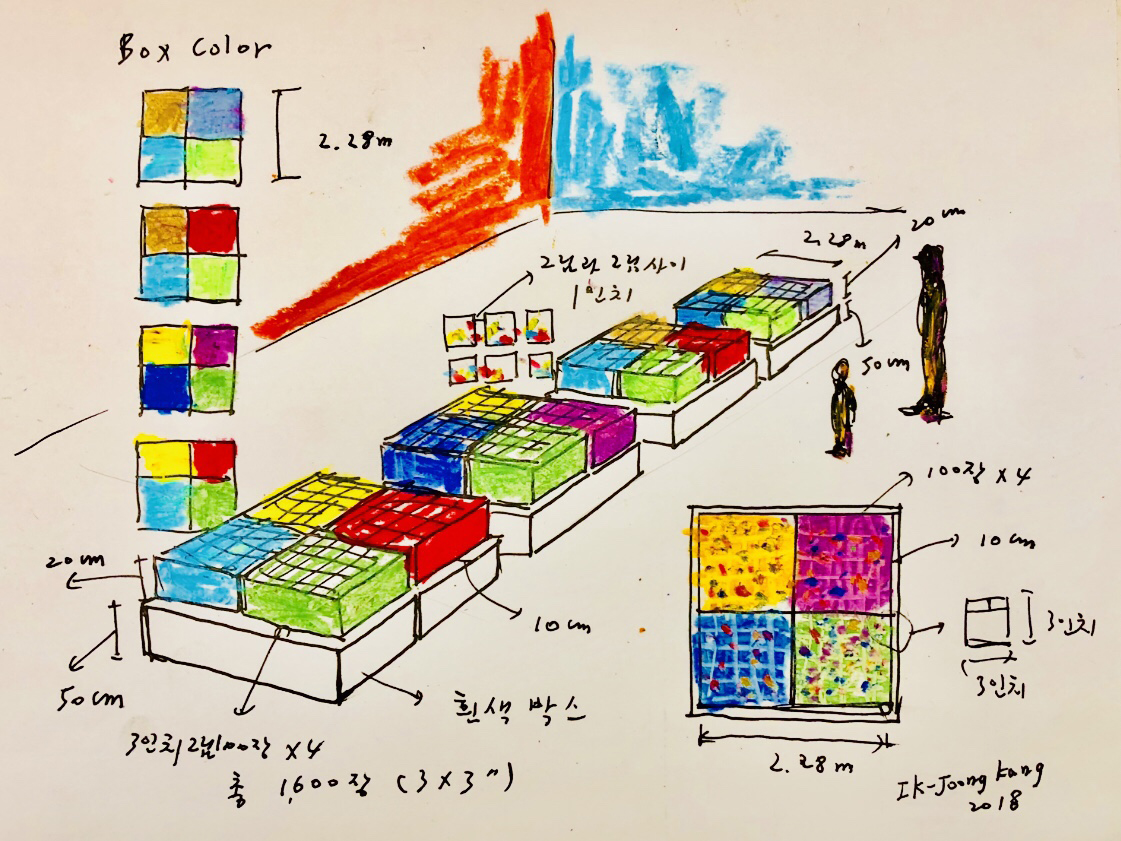

Ik-Joong Kang, who early on in his career was awarded the Venice Biennale Special Merit prize in 1997, is among Korea’s foremost contemporary artists. He is known for his moon jars and 3 by 3 inch canvases, which over the past three decades have multiplied to create larger narratives through monumental installations.

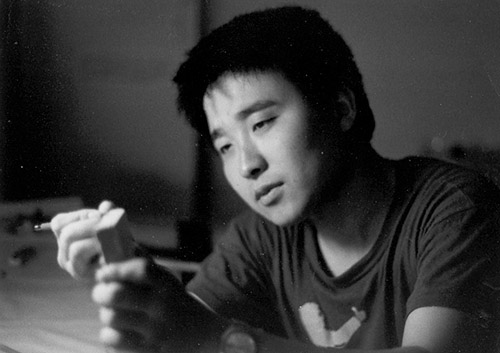

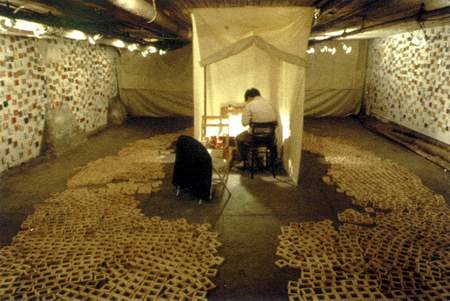

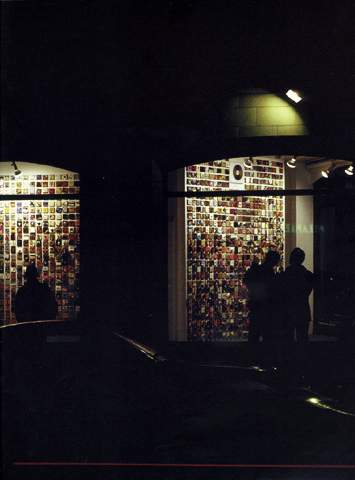

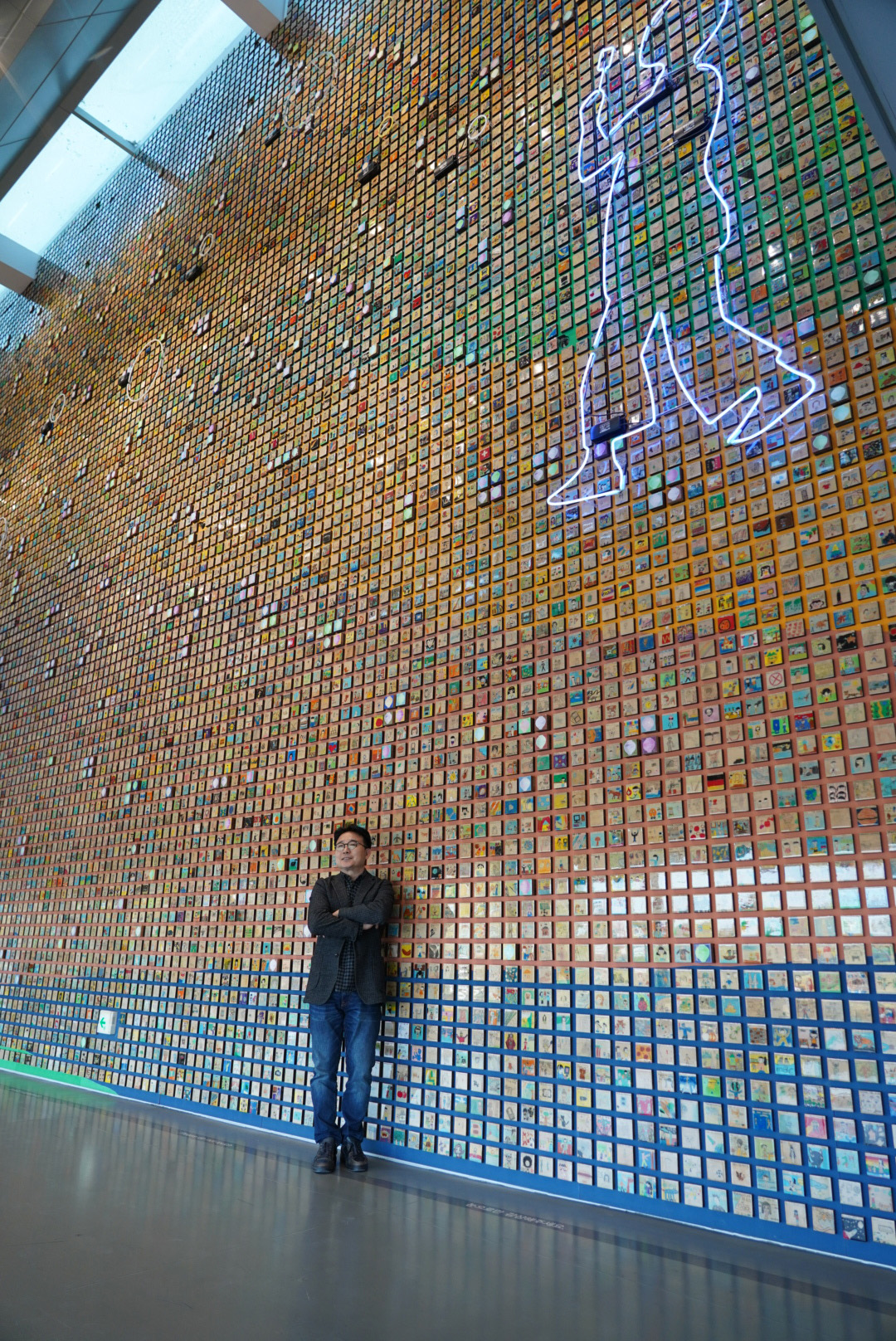

Ik Joong Kang in his studio, 2014. Photo by Christine Lee.

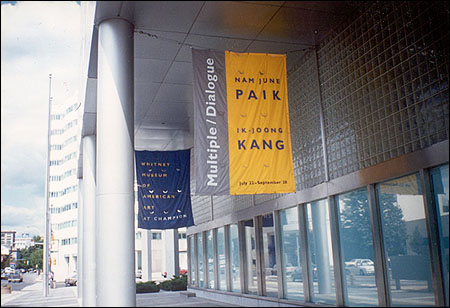

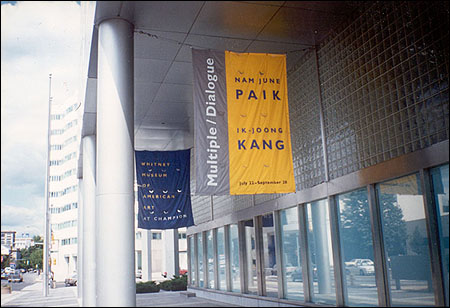

Ik-Joong Kang was born in Cheongju, Korea, in 1960 and received his BFA from Hong-Ik University in Seoul, Korea, in 1984. He moved to New York in 1984 to study at Pratt Institute where he received his MFA in 1988. He has exhibited widely, including a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris, New York (1996); a two-person show with Nam June Paik at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Champion, Connecticut (1994); and group exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1996); 47th Venice Biennale (1997), Ludwig Museum, Cologne (2000), National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul (2010) and the Korean Pavilion for the Shanghai Expo (2010).

Art Radar talked to Kang about his artistic inspirations, and the importance of community and humanity in his works.

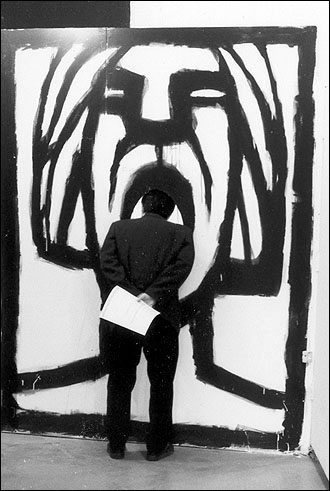

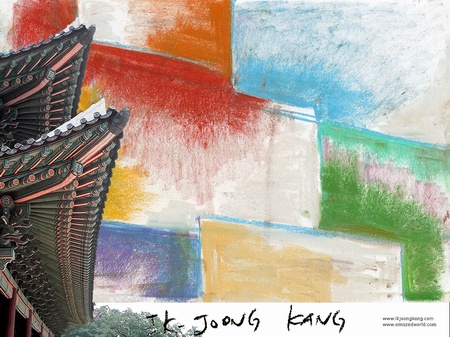

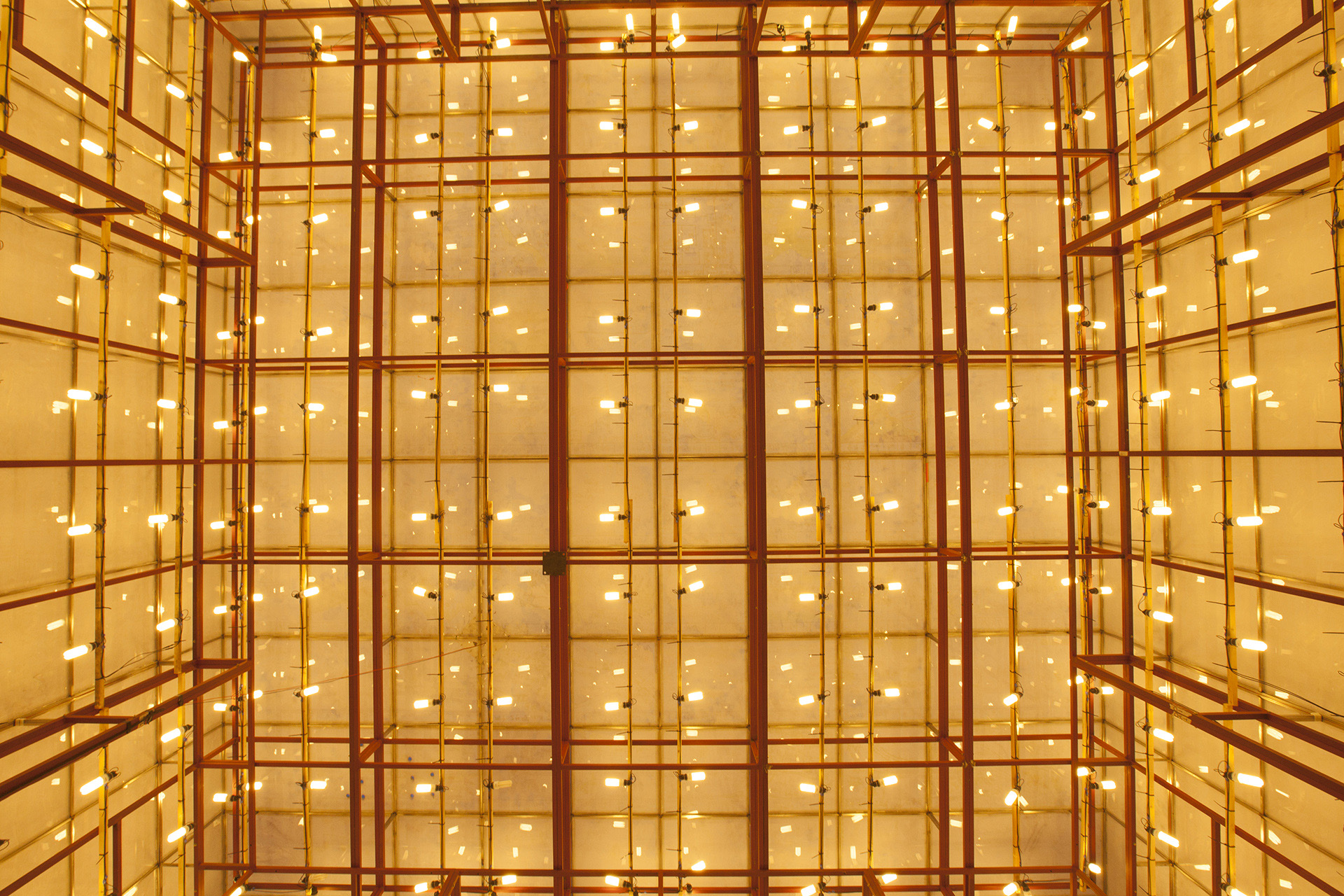

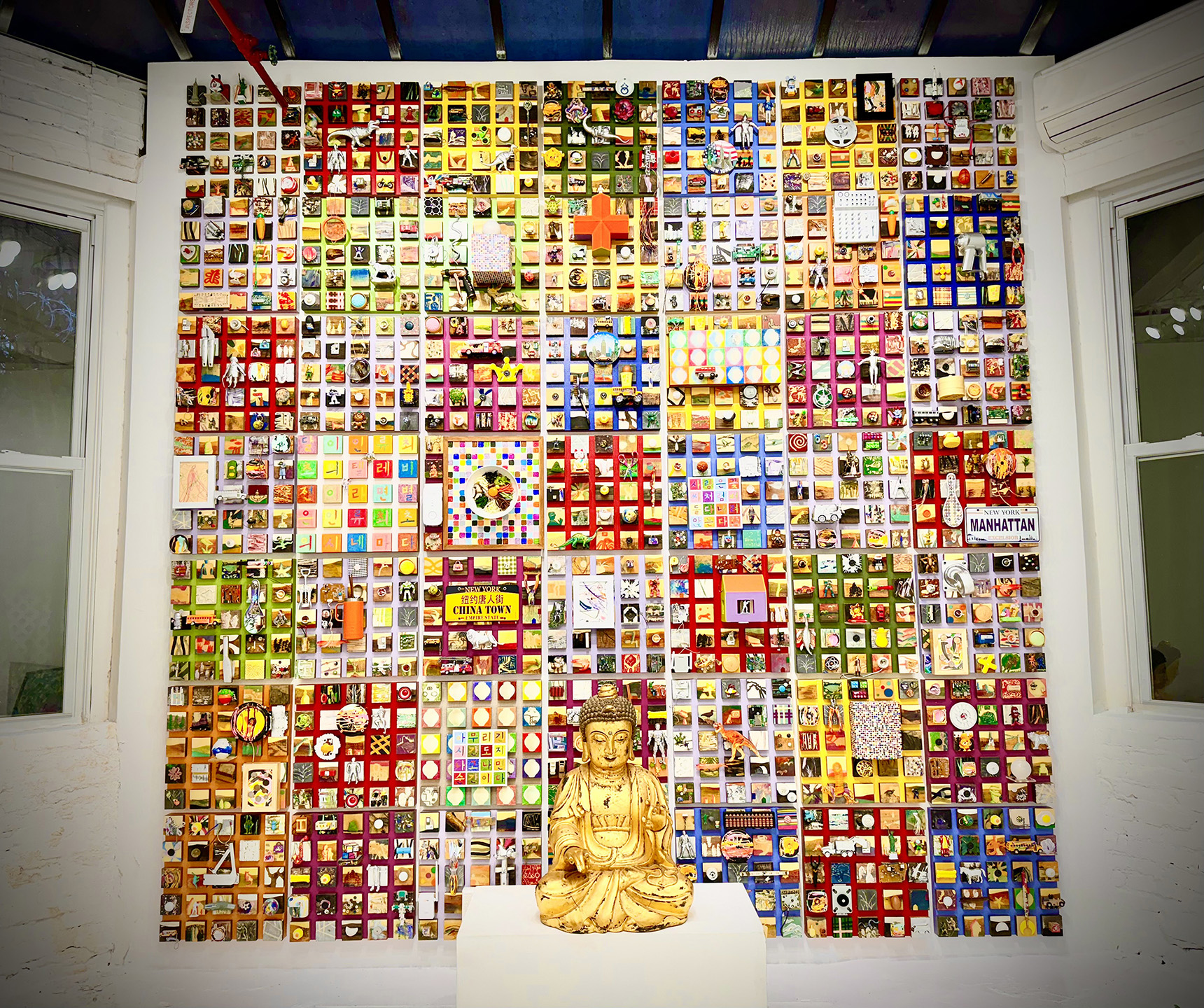

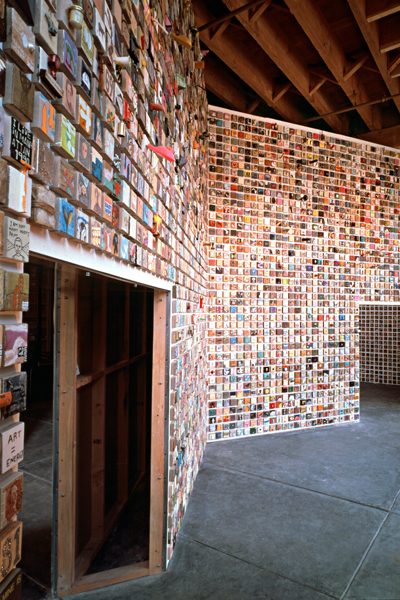

Ik-Joong Kang’s studio 2014. Photo by Christine Lee.

You were born in South Korea and moved to New York in 1984 to attend the MFA programme at Pratt Institute. Could you describe your background and why you became an artist?

I was born in Cheongju, about 100 km south of Seoul, and grew up in the Itaewon district of Seoul during the sixties and seventies. At that time, Itaewon was like an island within the city where many foreigners lived, especially US military personnel and their families. Many Koreans who lived there had jobs related to the US military base nearby. My family chose the area because it had affordable housing. Upon my arrival in New York, I experienced less cultural shock than most of my Korean friends, because I already felt comfortable in the American culture.

My interest in becoming an artist could maybe be traced back to a day when I was six or seven. I drew a sketch of my grandmother’s passport portrait and showed it to my uncle. I remember he literally jumped up and down exclaiming that I must be the reincarnation of one of our great grandfathers. Our family was poor but we were proud to be descendants of many famous artists and scholars. My uncle’s jump changed my life.

Ever since that day, I became quite a diligent artist all throughout high school. But after enrolling in one of the most prestigious art schools in Korea, Hong-Ik University in Seoul, somehow my interest in becoming an artist suddenly faded away. I sensed that something was missing and I soon realised art school was not the best choice for me. I was yearning for something to fill a personal void, somewhere to find the answer and perhaps, most importantly, somewhere to escape. In 1984, I arrived in New York with not much money and the knowledge to survive. But as I think upon it now, New York was the right place for me. With its artistic pulse, New York City was the place where my uncle’s Confucian belief in the power and continuity of my ancestry would best be realised after all.

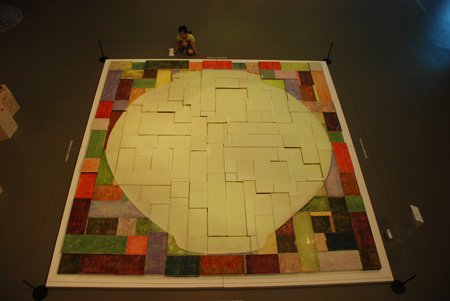

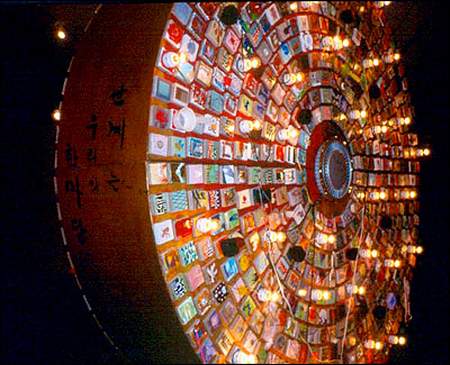

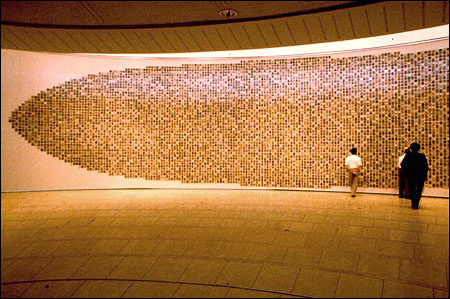

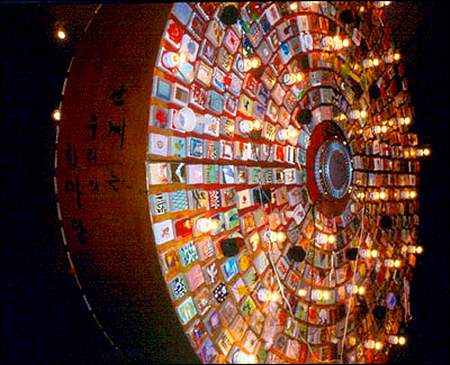

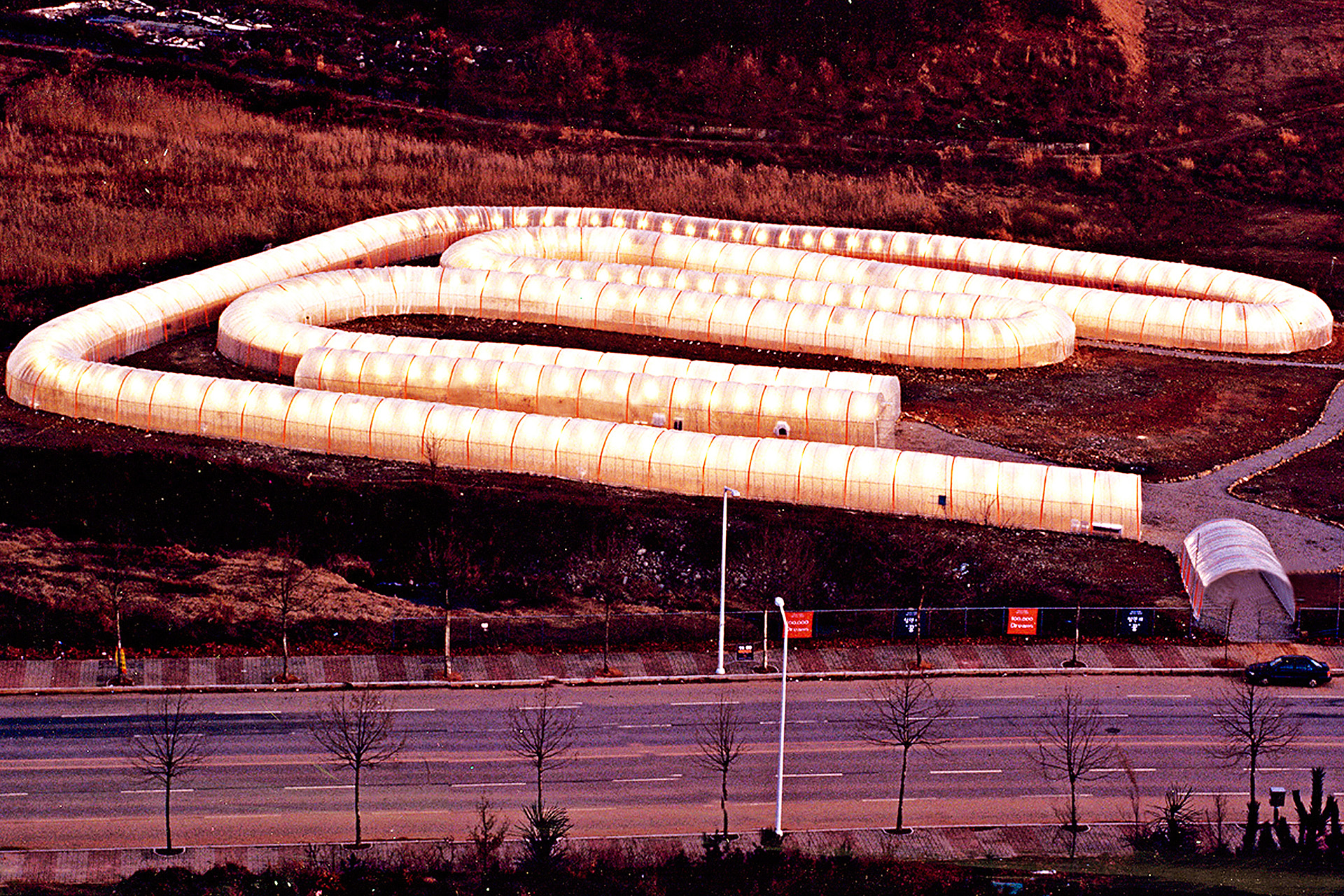

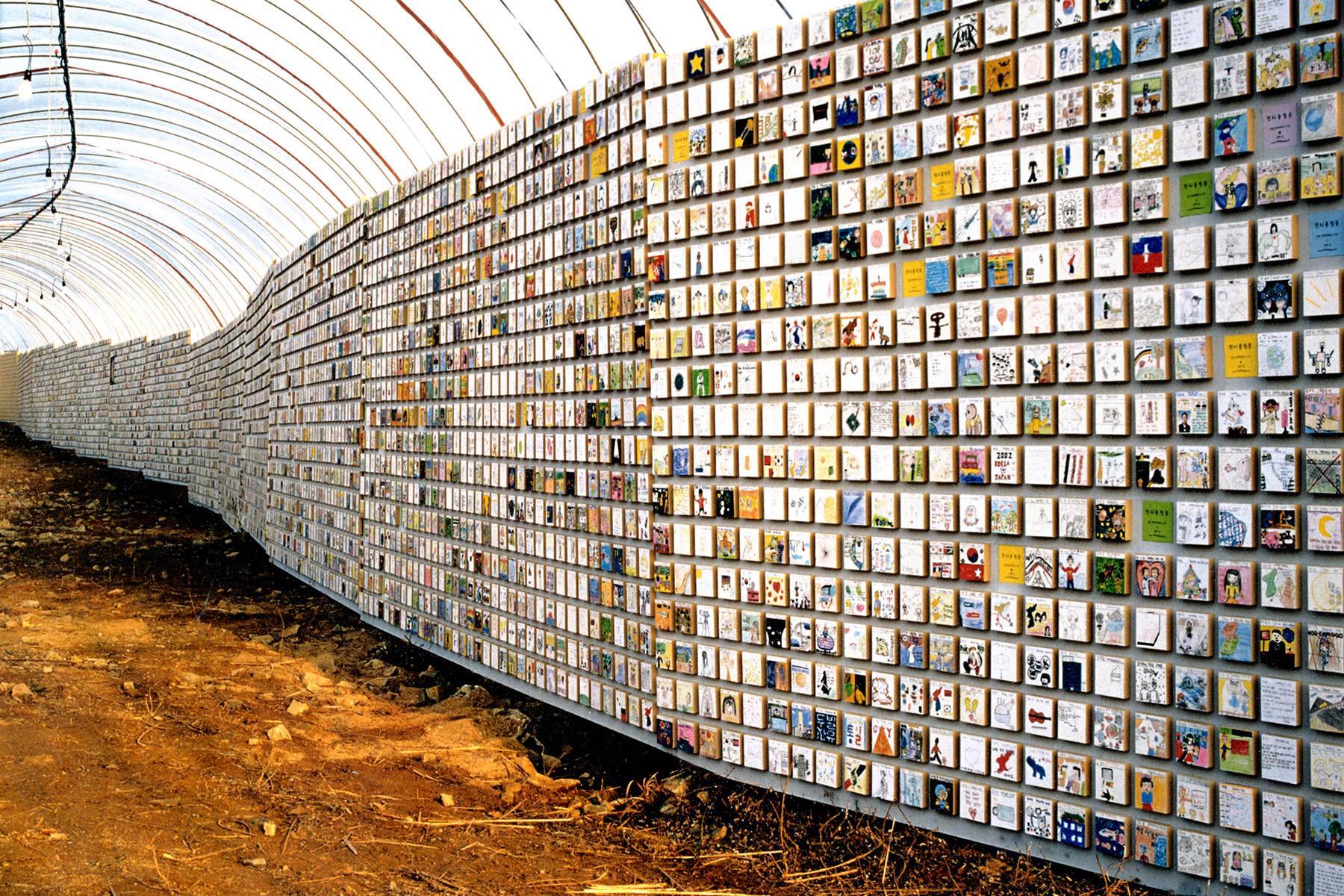

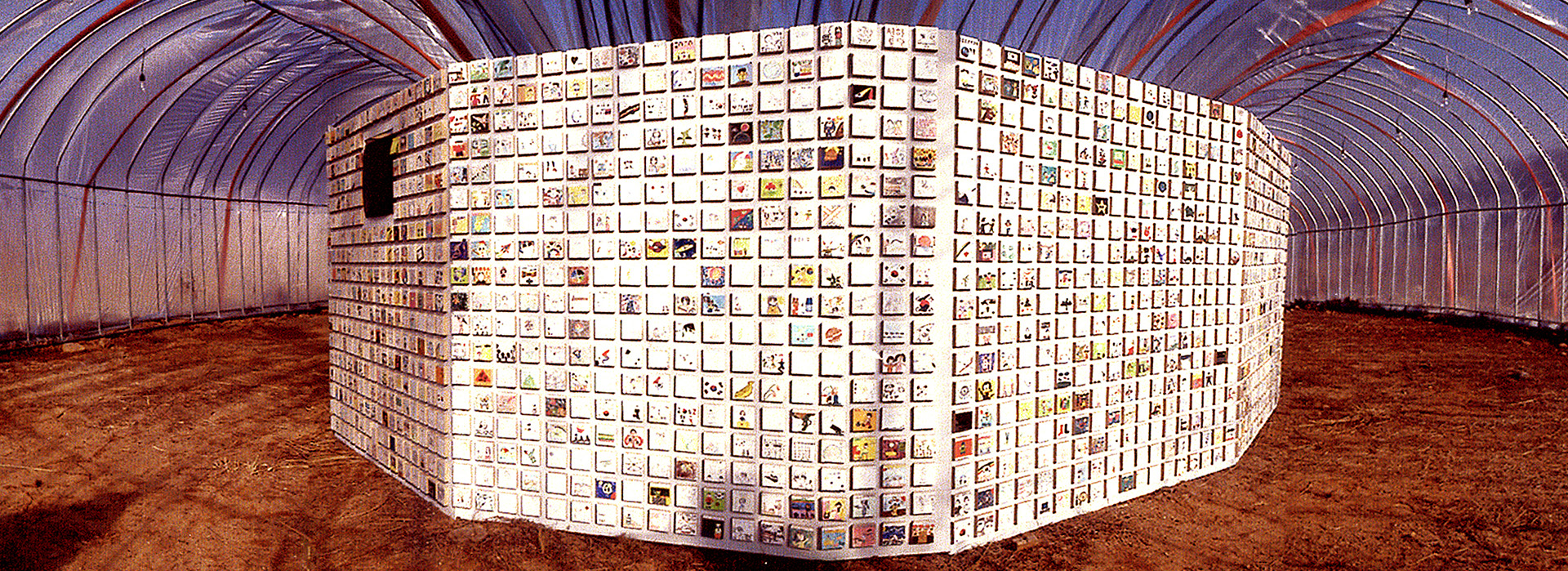

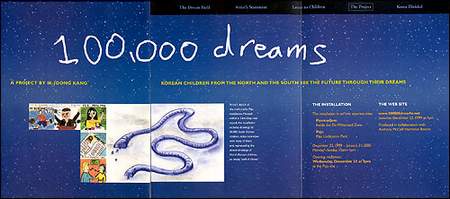

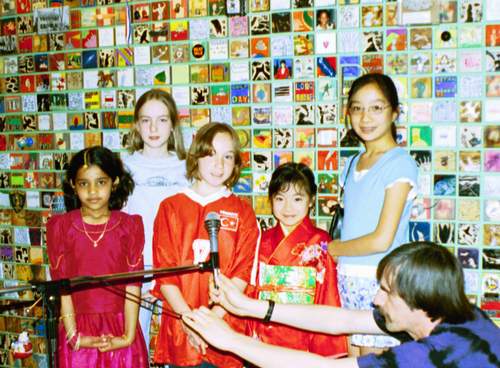

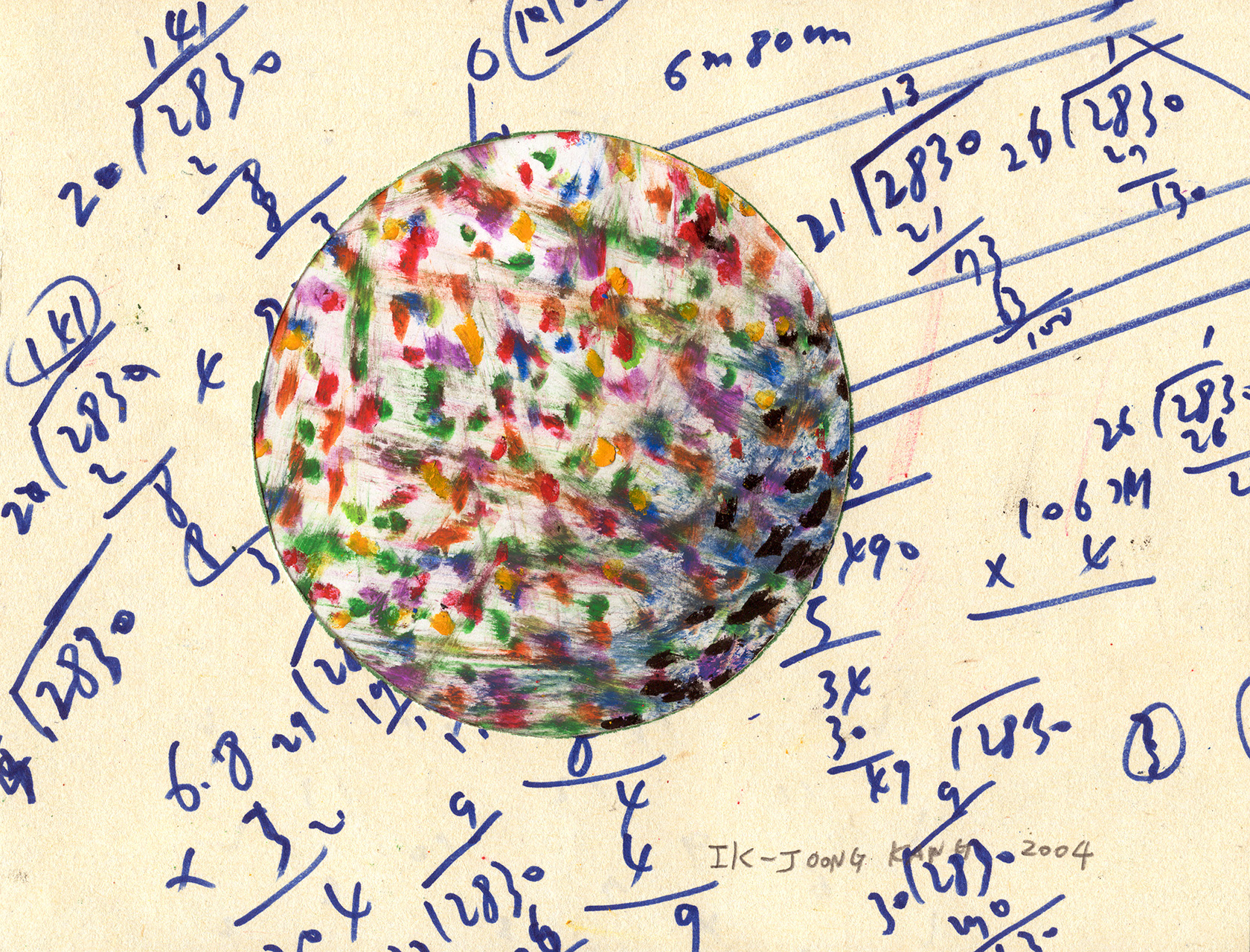

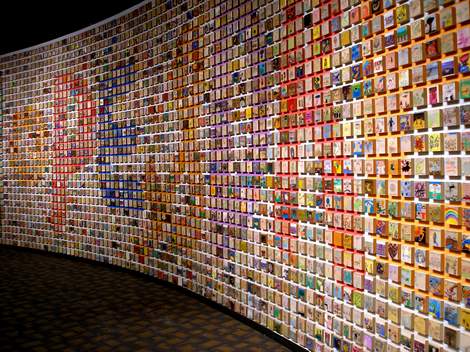

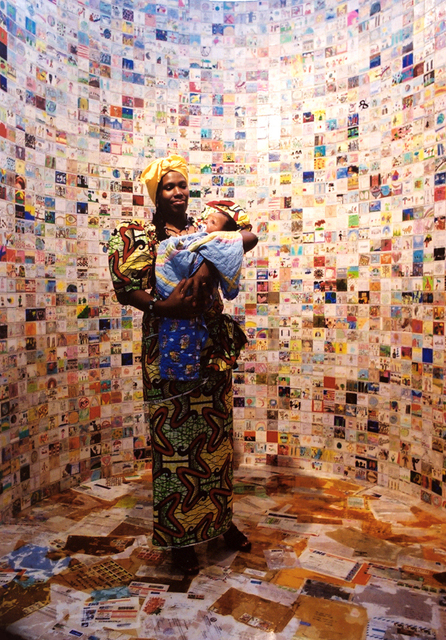

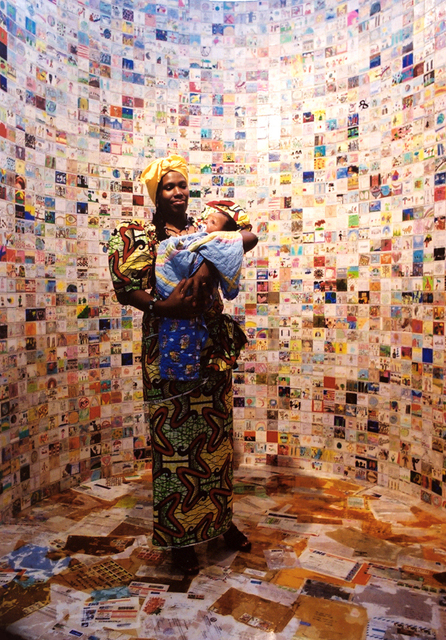

Ik-Joong Kang, ’100,000 Dreams’, 1999-2000, 60,000 children’s drawings, Paju, Korea. Image courtesy the artist.

Storing dreams in moon jars

What are your major artistic influences and how do they relate to your work? Has it changed over time? What inspires you as an artist today?

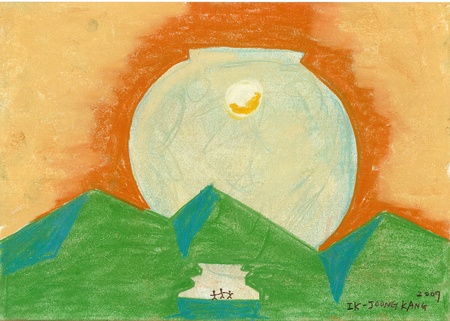

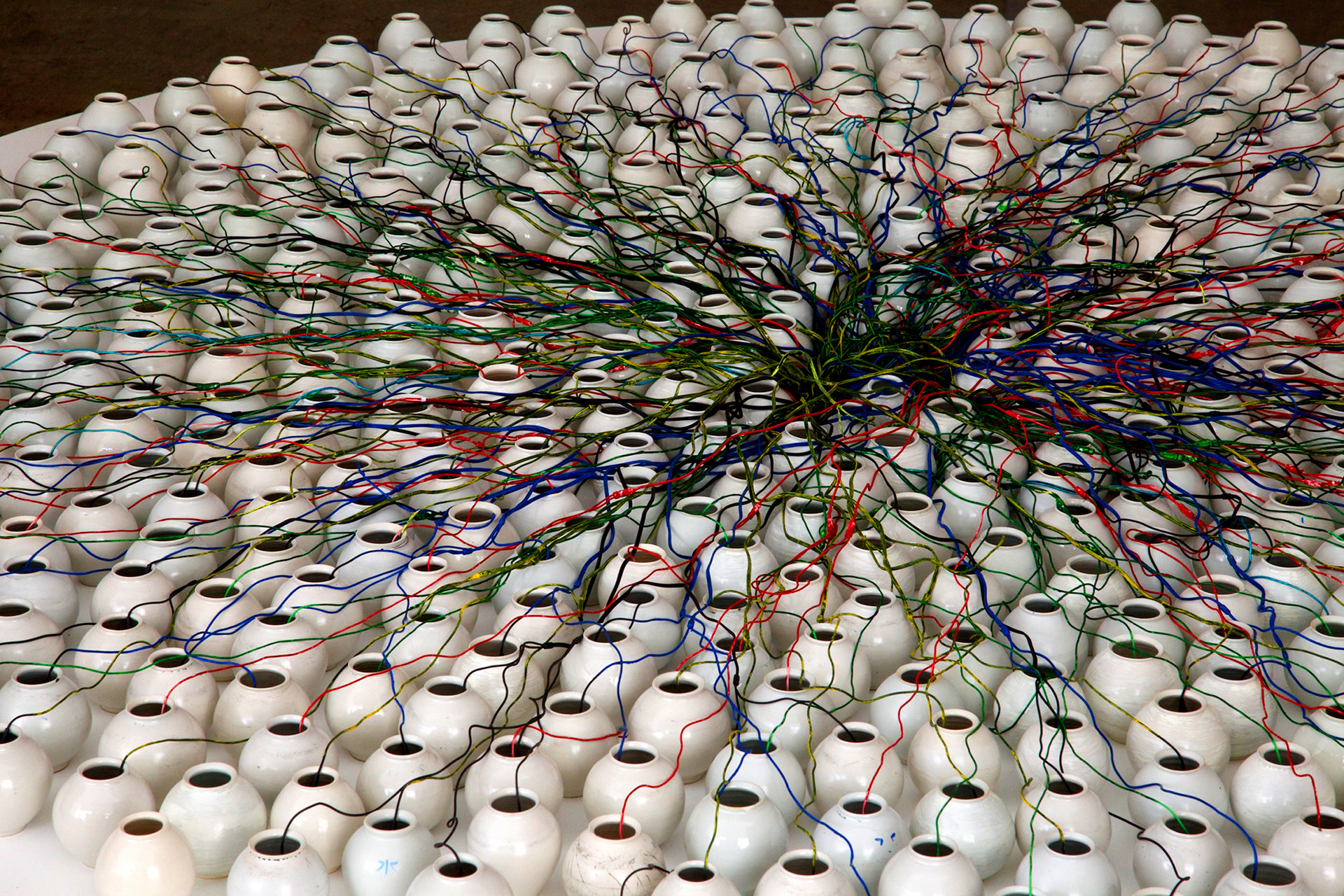

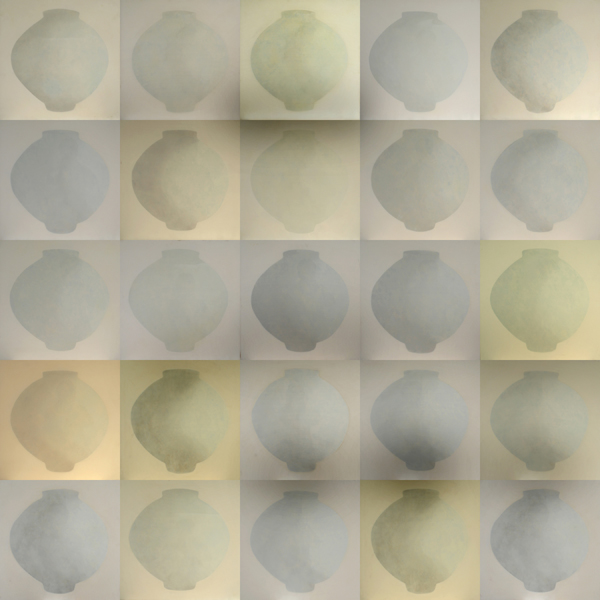

The moon jar is probably my main influence. I believe the moon jar is like a human being, filled with air and spirit. The traditional moon jar, made during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1911), is a simple and plain jar, deep white [in colour] with the shape of a moon. The surface of the moon jar dimly glows just like the moon and its imperfections are admirable. Because a potter used particularly extra soft clay, he had to first make the bottom half — separate from the top half — then connecting the two semi-spheres: two parts into the kiln to become one.

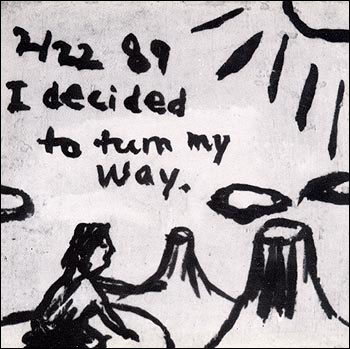

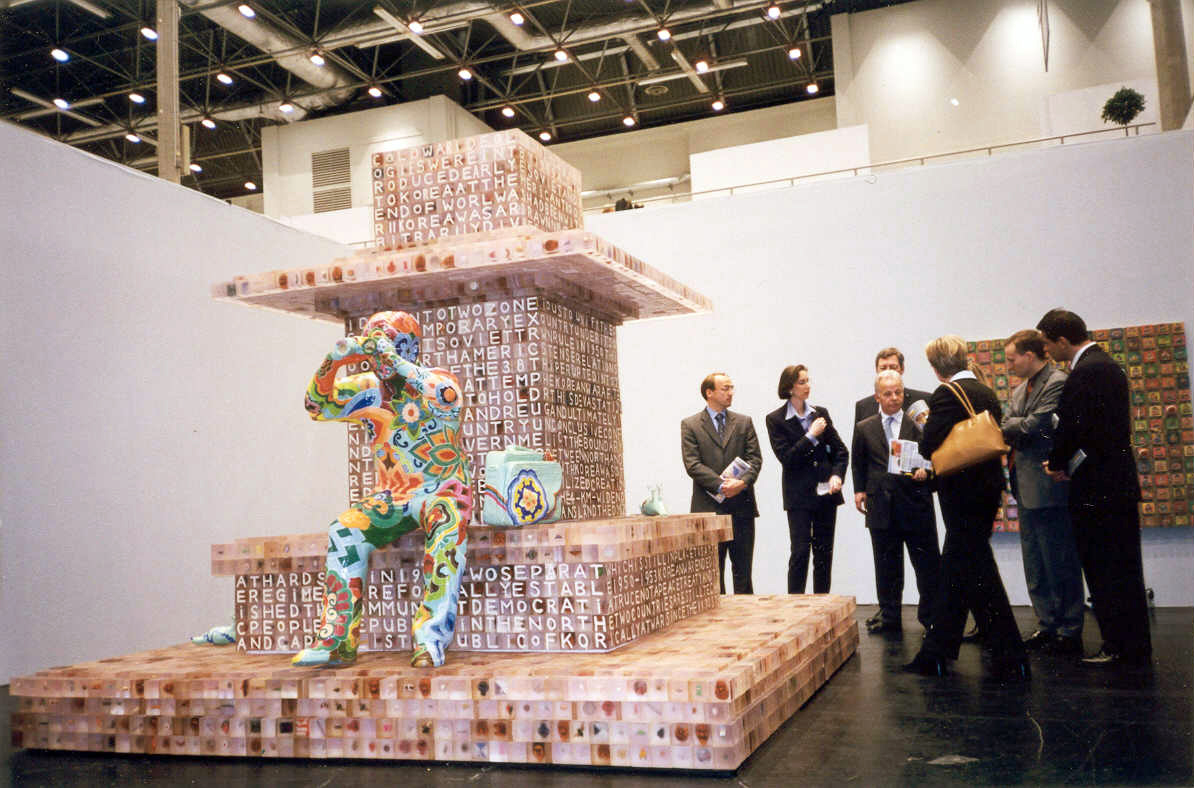

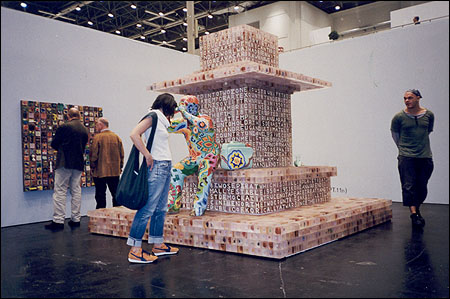

10,000 Dreams (1999-2000), my first outdoor installation reflective of the idea of connecting the two Koreas, was based upon the process of making the moon jar. It becomes a moon through this transformation. A notable fable goes that the Chinese poet Li Bai (701-762) drowned when, sitting drunk in a boat, he tried to seize the moon’s reflection in the water. The moon was the place of immortality and a connecting station to the other world, a place where people store their dreams.

The sky is blue before the full moon night and it wears the bright new dress on the morning of New Year’s Day. Right before the storm the sky is mild green. And it seems layered before winter blizzard comes. – Li Bai

I also found a similar inspiration in the way one makes Bibimbap (a traditional Korean dish). Bibimbap is usually made from mixed rice with bits of meat, fish, vegetables and seasoning. Although simple, the numbers of variations to this dish are infinite and vary with individual circumstances and preference, the underlying constant always being the rice. So long as there is a bowl of rice with a scoop of Gochoojang (Korean chili-paste), one can make Bibimbap, simply by throwing everything together and adding the remaining touches. Just like making a moon jar, it holds flexibility and embraces everything within a given structure.

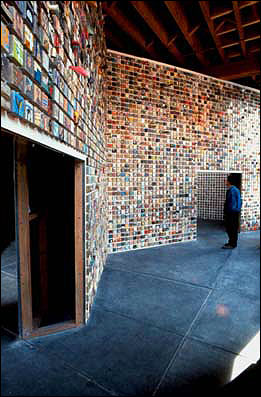

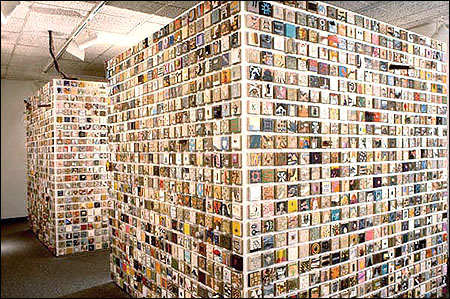

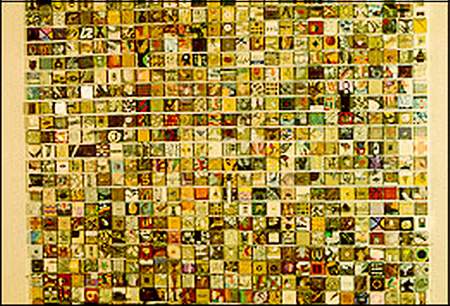

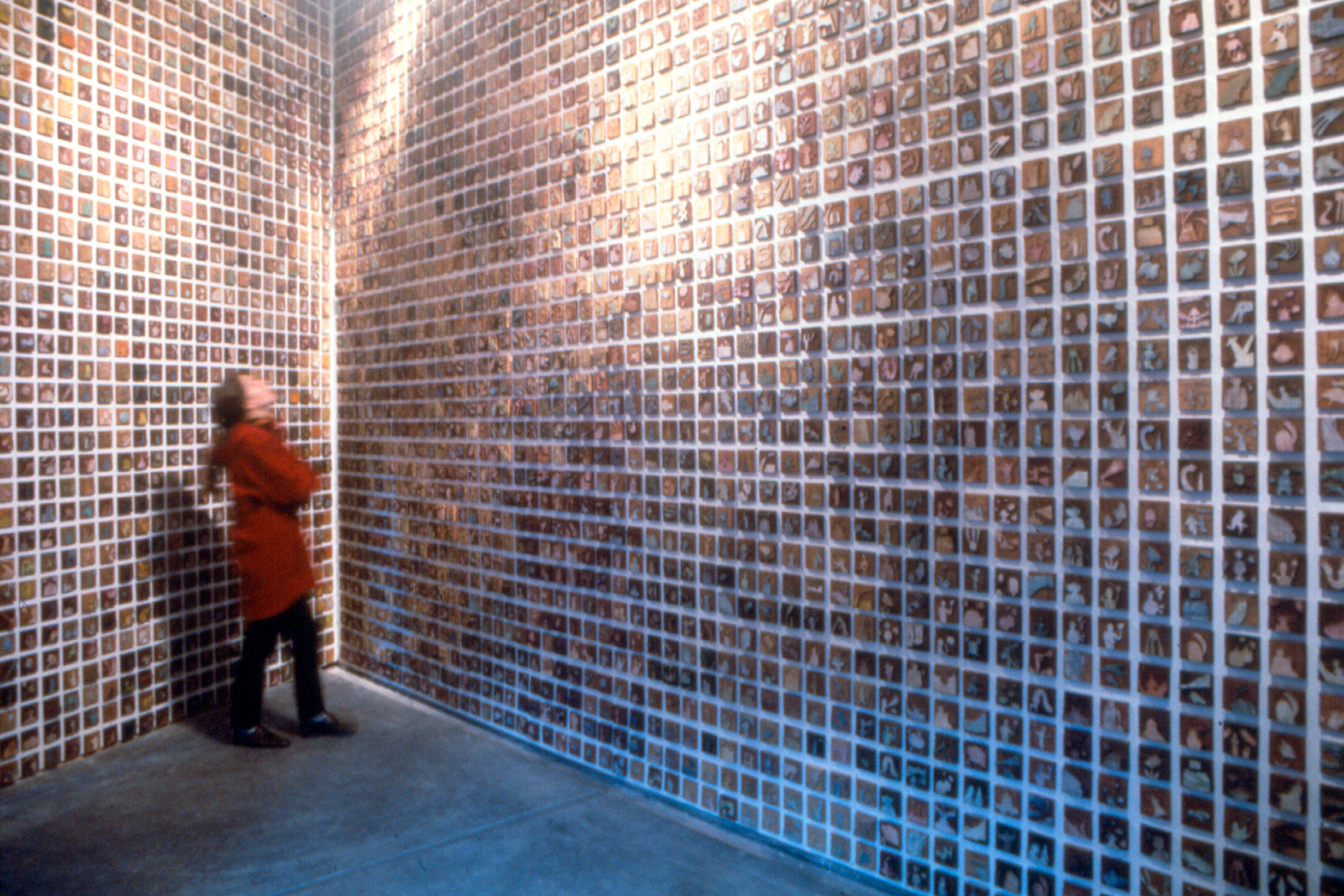

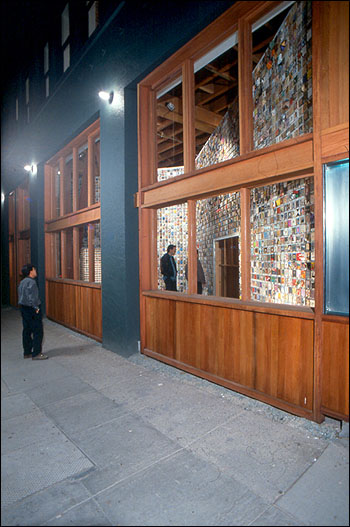

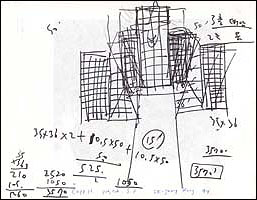

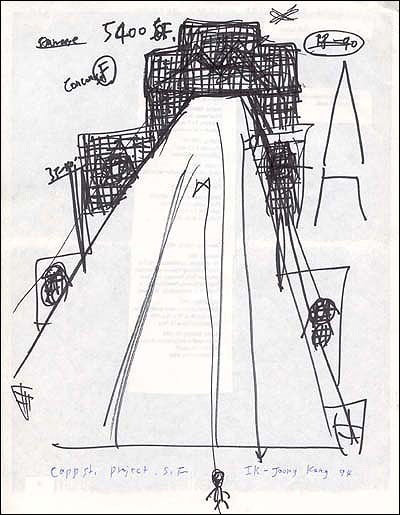

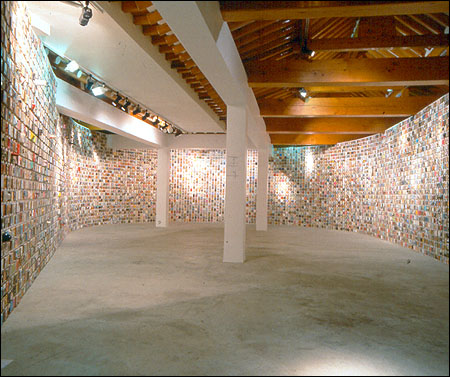

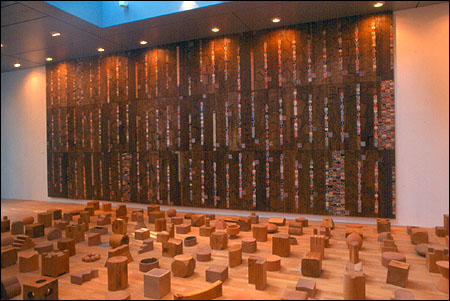

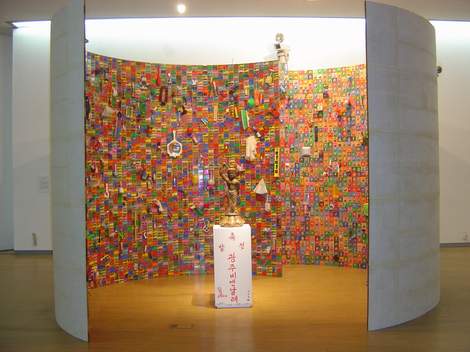

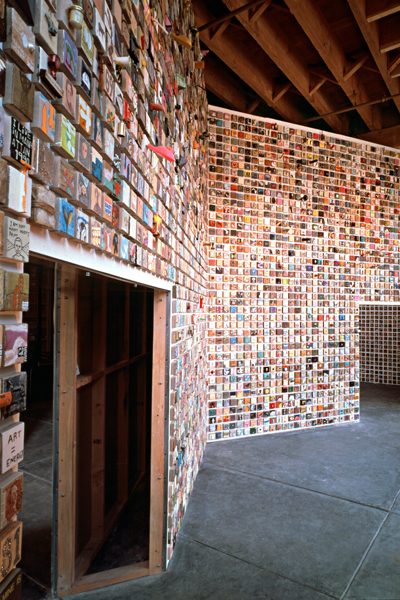

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Everything Together and Add’, 1994, Capp Street Project in San Francisco. Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art. Image courtesy the artist.

The title of the installation Throw Everything Together and Add at the Capp Street Project in San Francisco in 1994 came from the idea of making Bibimbap.

I believe the moon jar contains unlimited potential for connection to the outside world through the spirit of sharing and openness. My moon jar cannot be the moon jar from the Chosun dynasty. It might share the spirit of Chilsung Mudang [the shaman/priestess – Mudang – who worships the spirits of the seven stars – Chilsung] in Cheju Island in Korea, who worshiped the seven-star gods and simply performed her ritual dance before only the Seven Star Cider. She was able to do her performance without formal preparation. She knows how to connect with outside forces and doesn’t need a formal process or protocol. Similar to the master who created the moon jar, Chilsung Mudang’s performance was not focused on the appearance and rule so much, but more on her state of mind.

Breaking down walls through collaboration

Could you talk about some of the works or exhibitions that are or were most meaningful to you?

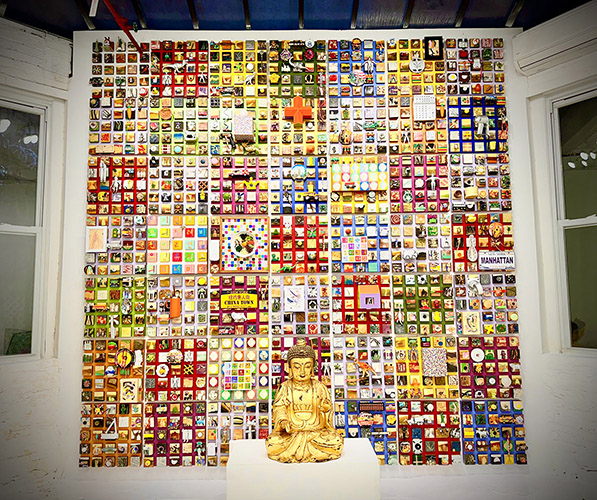

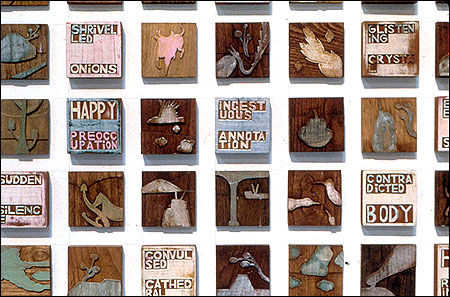

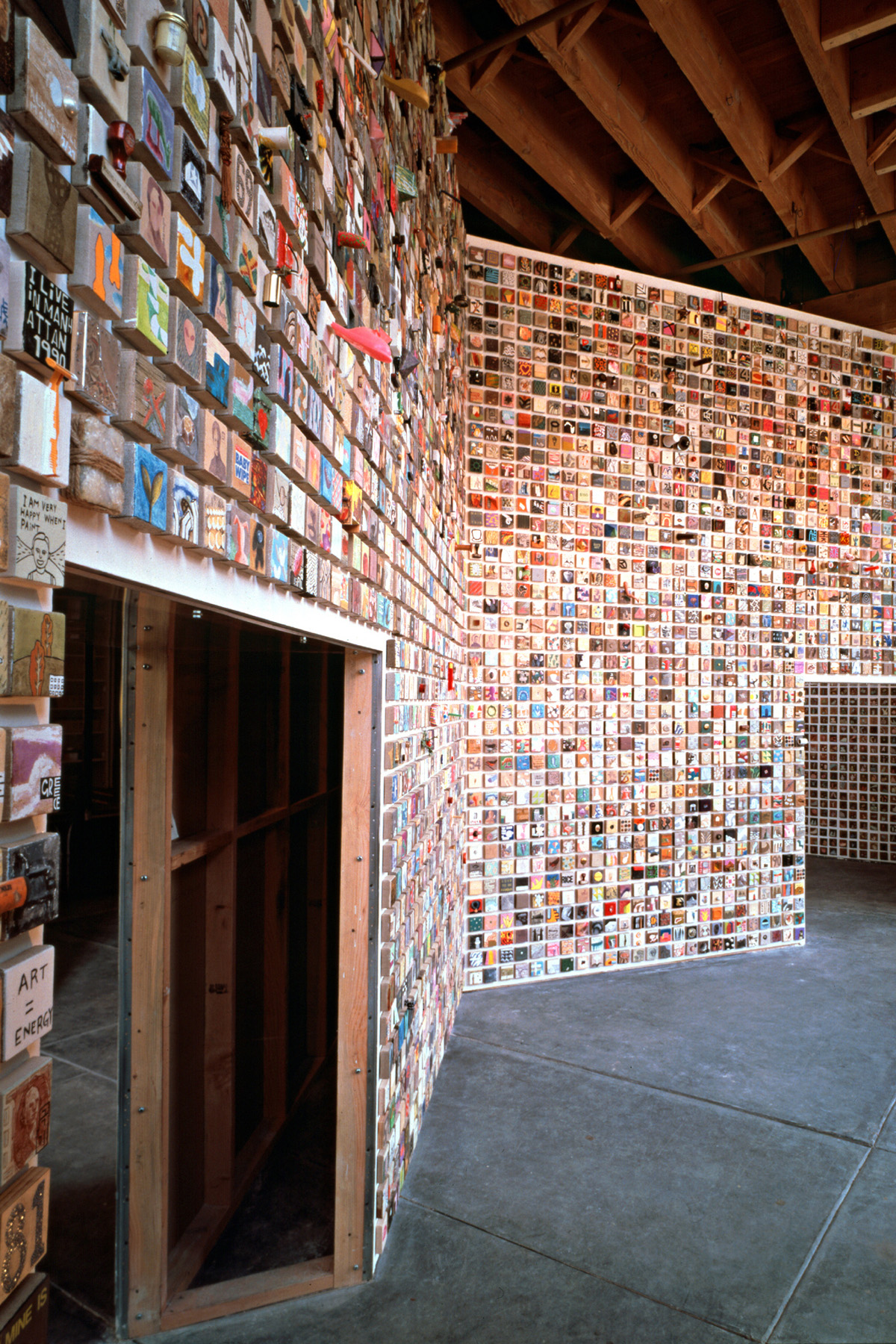

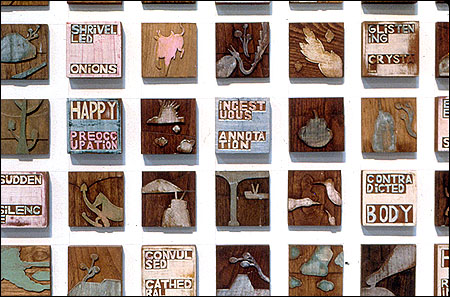

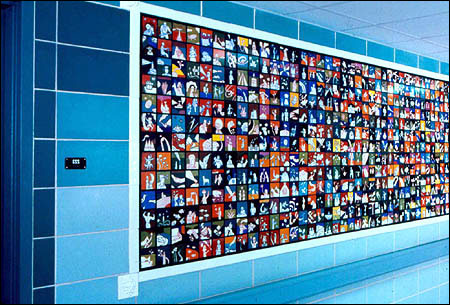

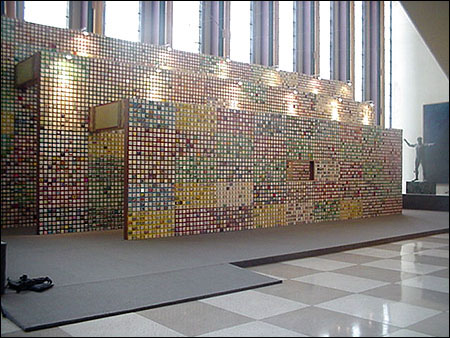

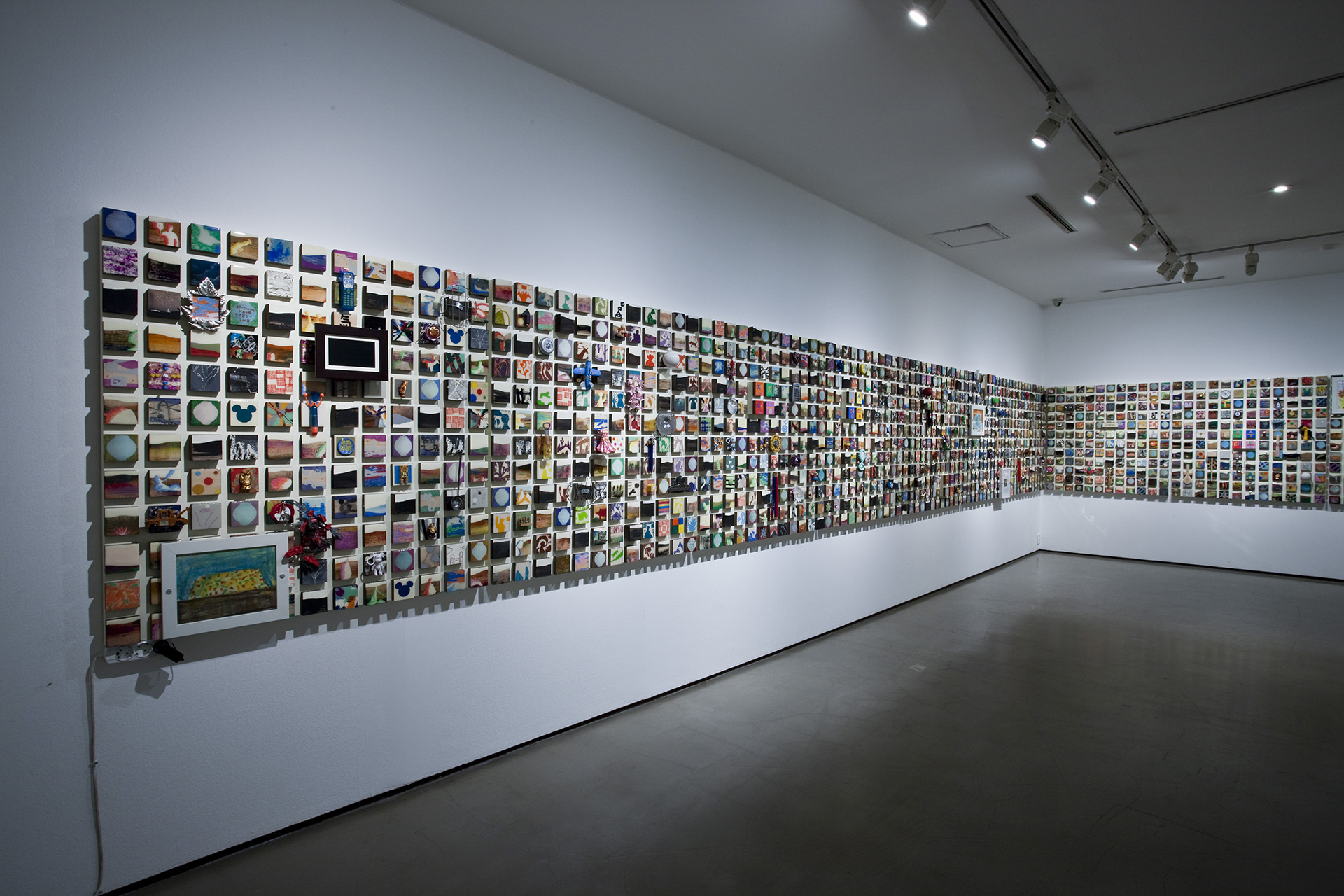

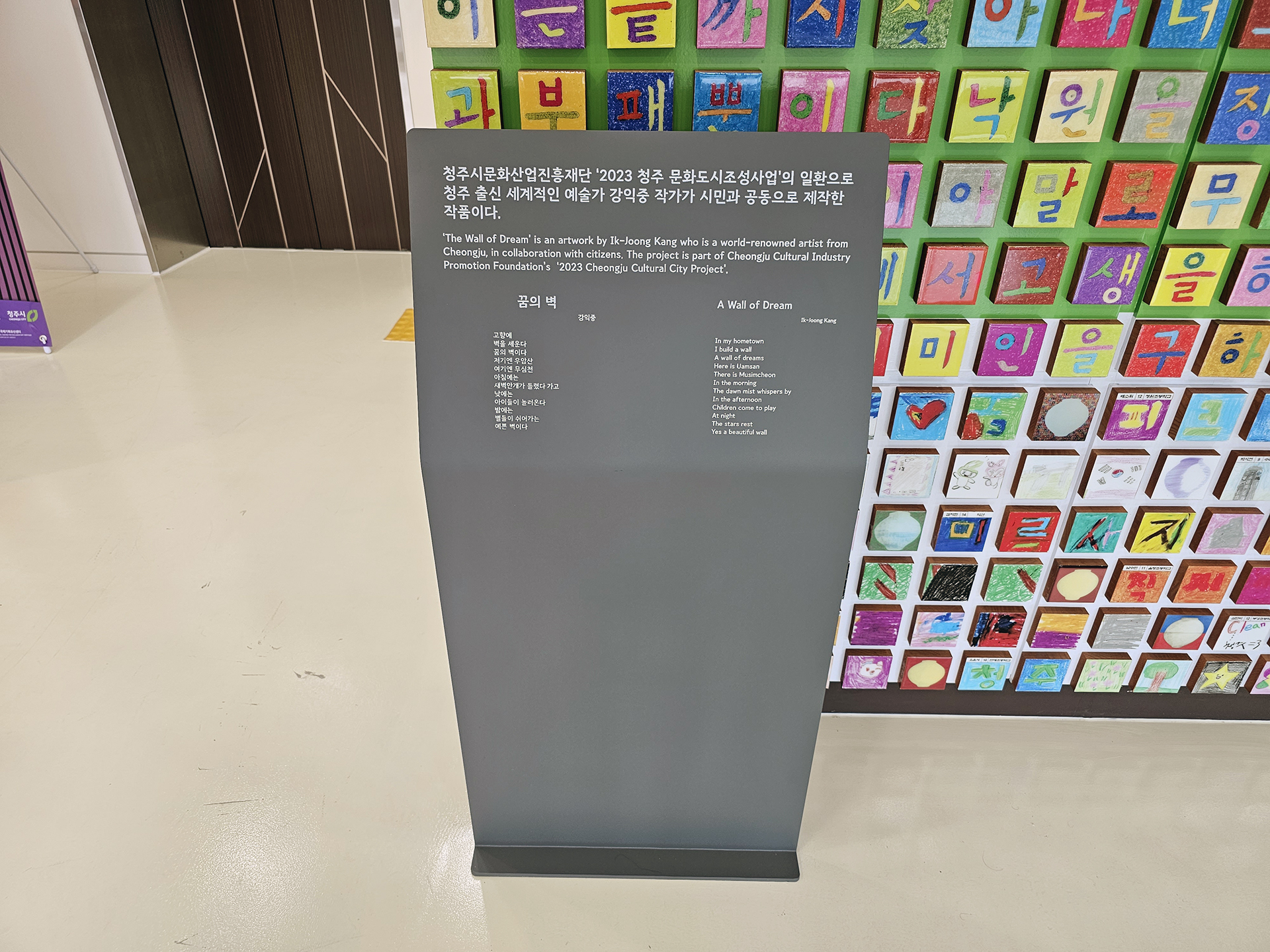

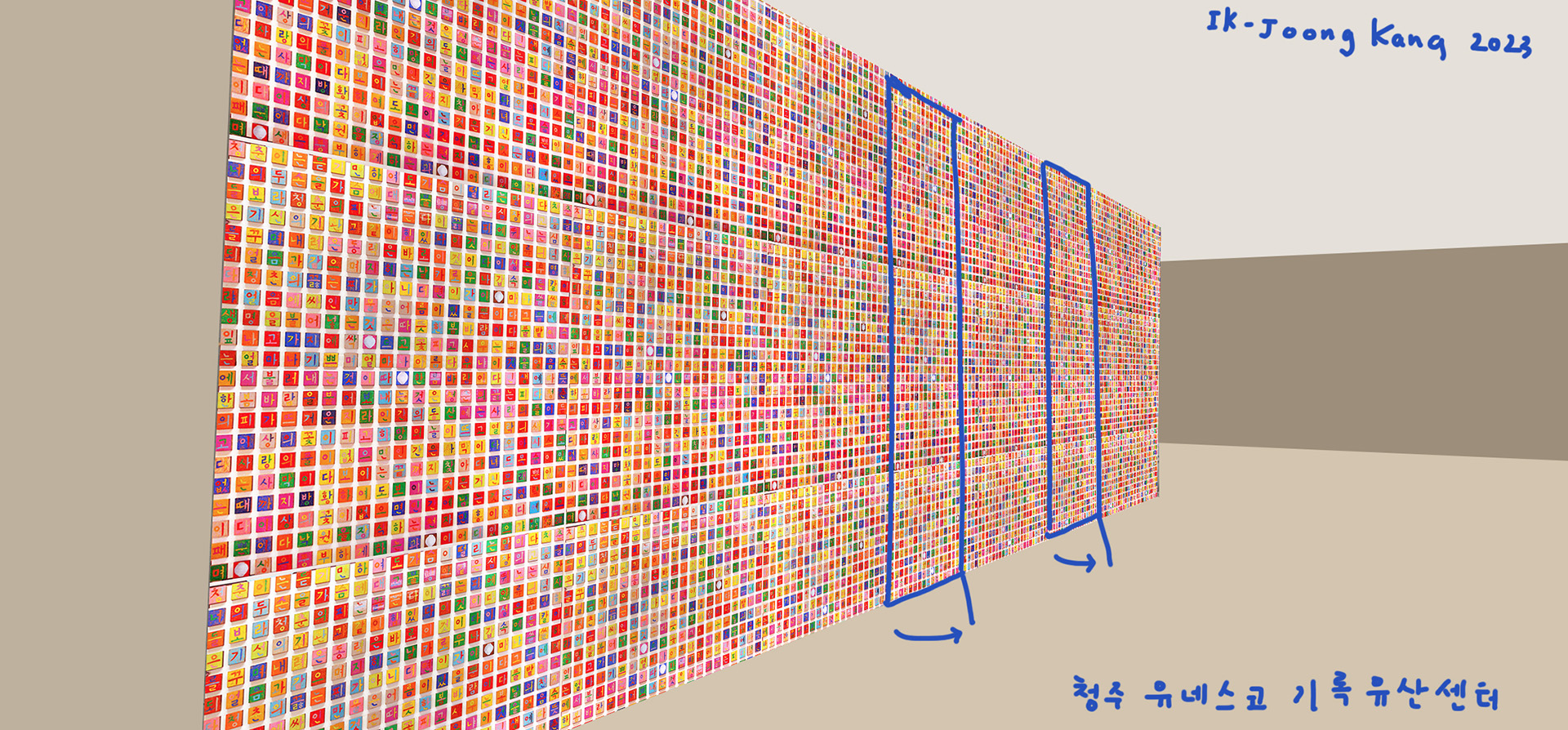

Happy World (2005) was a public project at the Princeton Public Library, New Jersey. It was more like a collaboration between the artist and community. The mural featured thousands of objects, most of which were donated by local residents who brought historical mementos, poetry, trinkets, trivia, toys, sculptures and even their babies’ first foot prints. Each item was catalogued, considered, and 1,000 of them were inserted and incorporated into a wall of three-by-three inch paintings and carved blocks by me. Happy World has since become a singular destination and, I think, the pride of the many local Princetonians who helped to create it. Working for the community along with their participation and contribution was the main idea of Happy World, and I learned that by making a wall of art we could break down the walls separating each other.

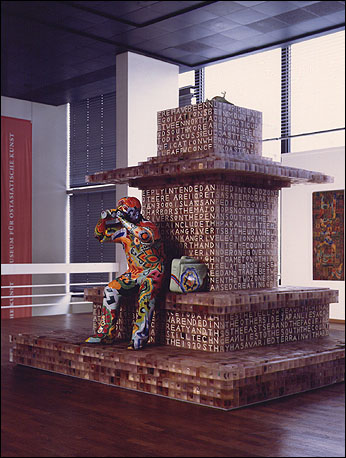

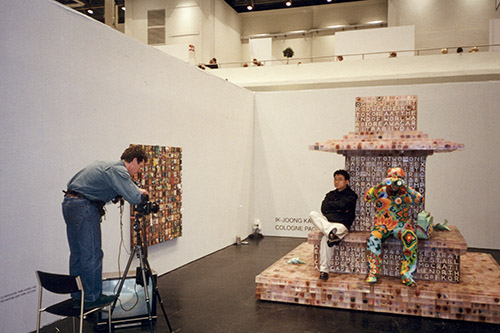

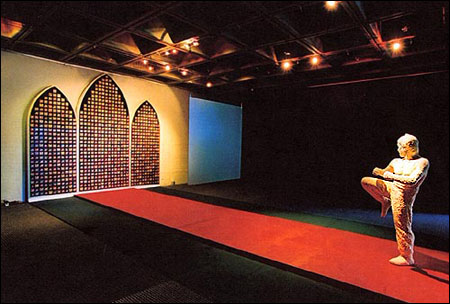

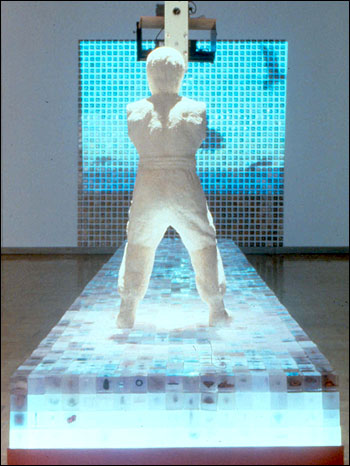

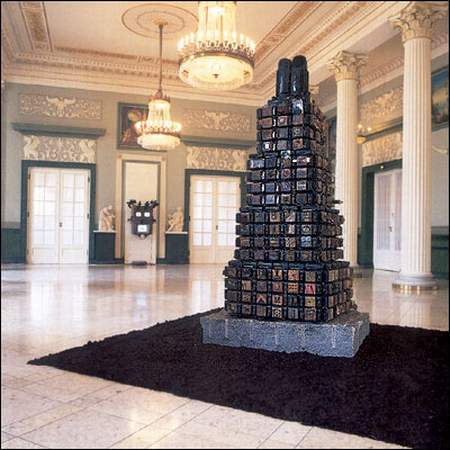

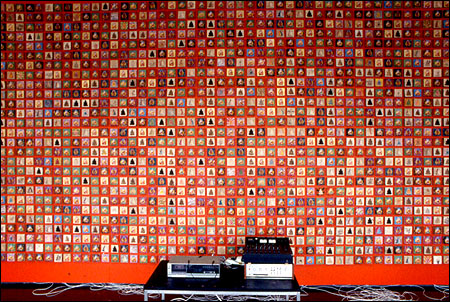

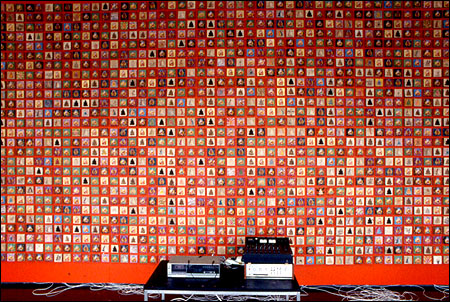

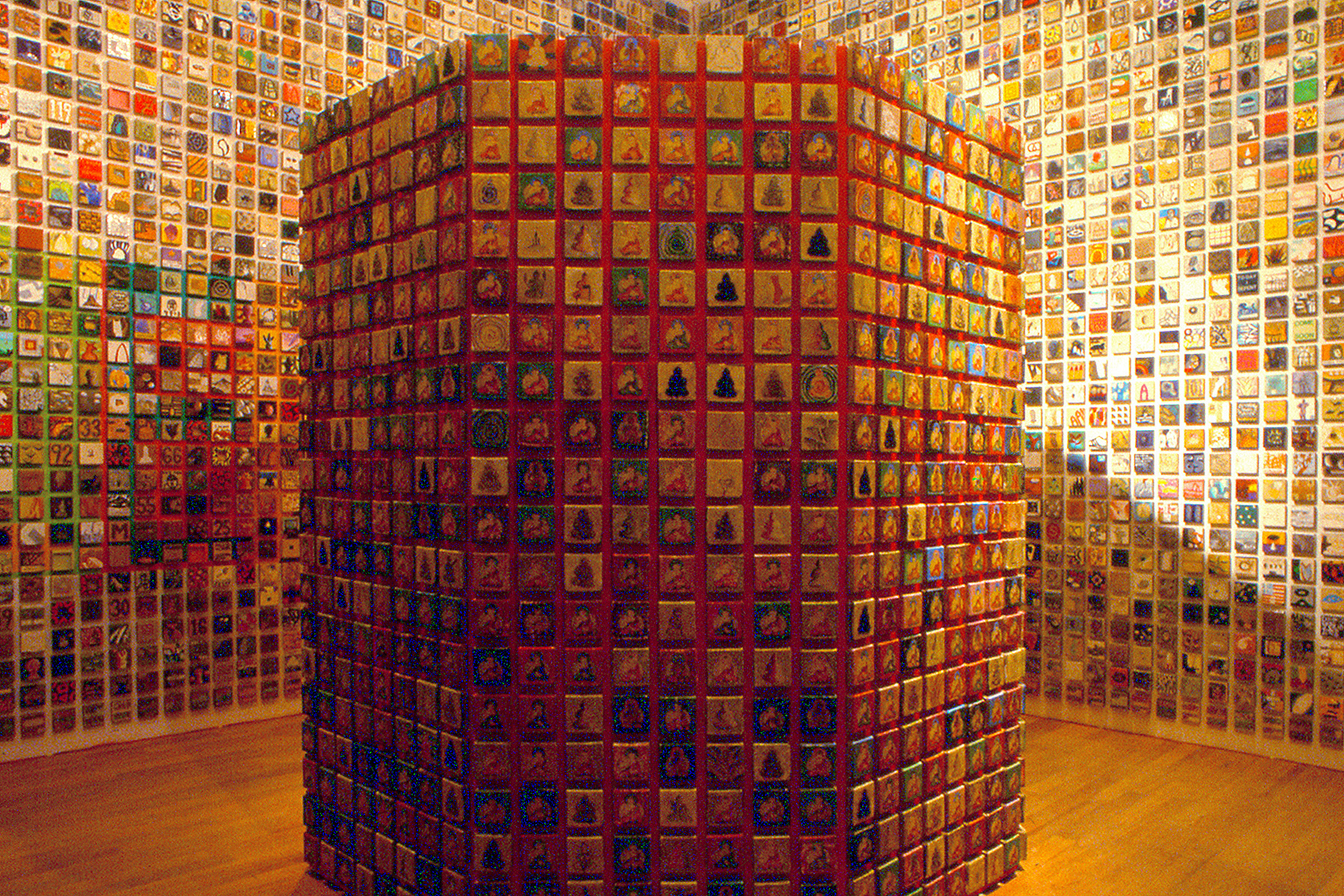

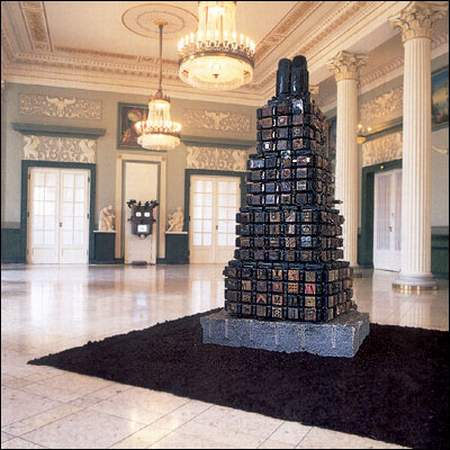

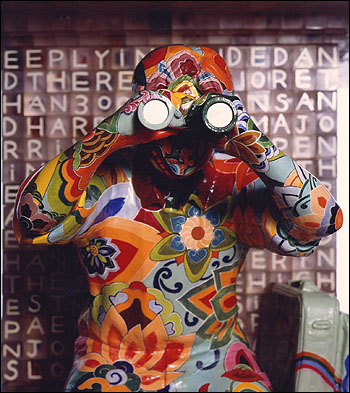

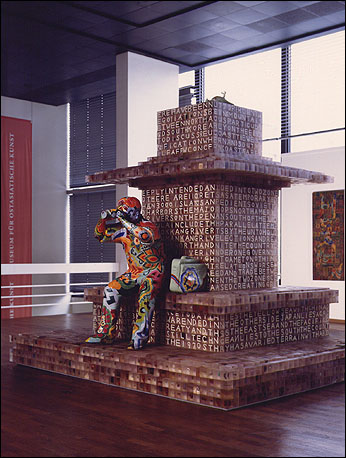

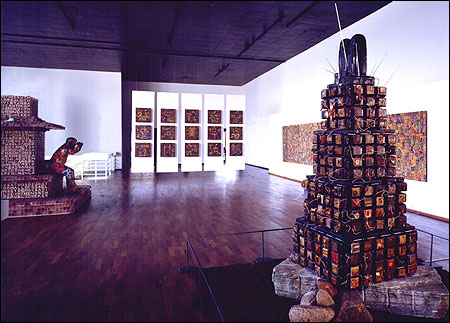

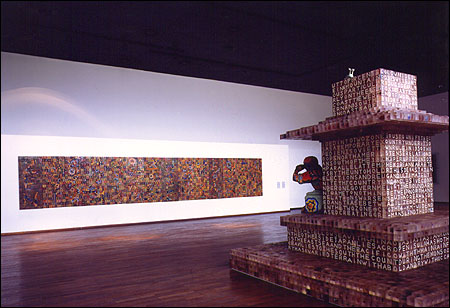

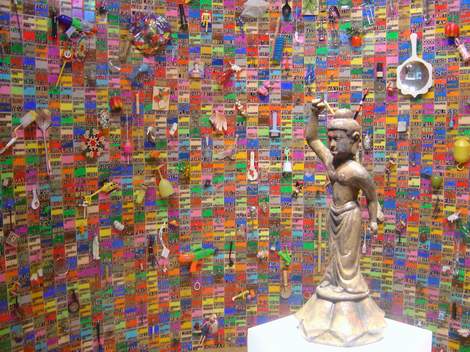

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Buddha Learning English’, 2000, 3000 English idioms on canvas, 7.6 x 7.6 cm each and chocolate covered Buddha, 108 x 40 x 40 cm. Collection of Museum Ludwig. Image courtesy the artist.

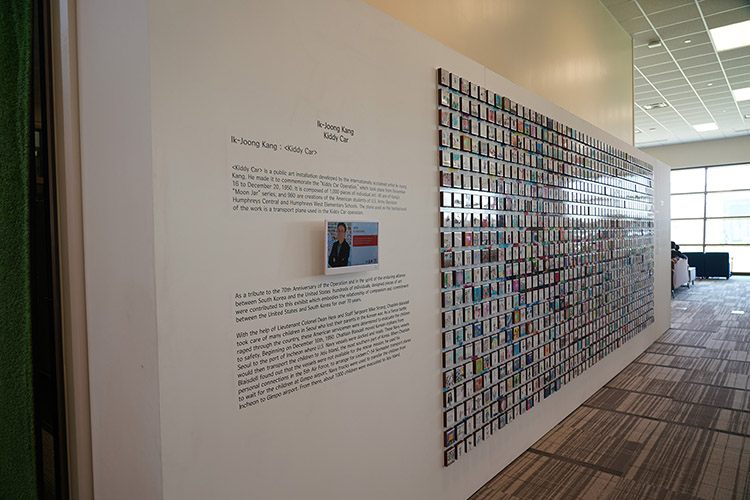

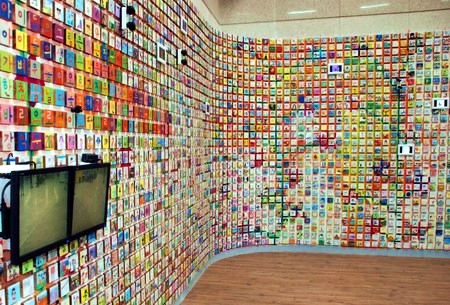

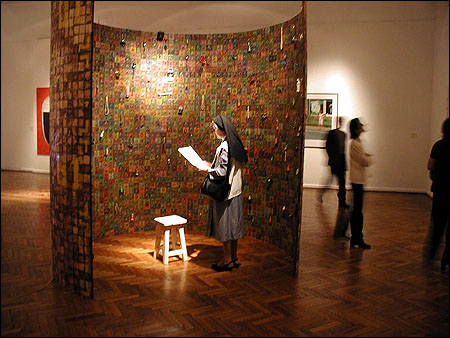

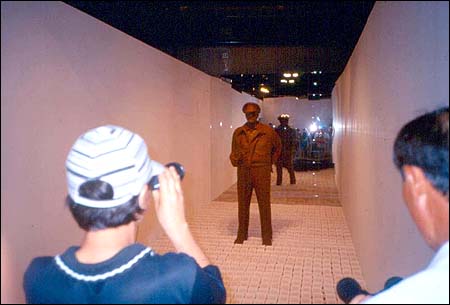

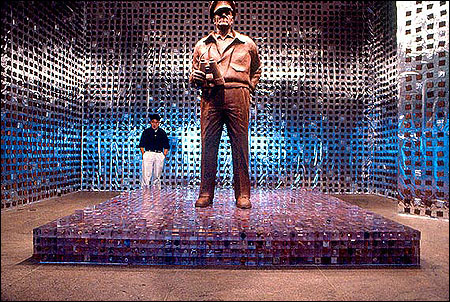

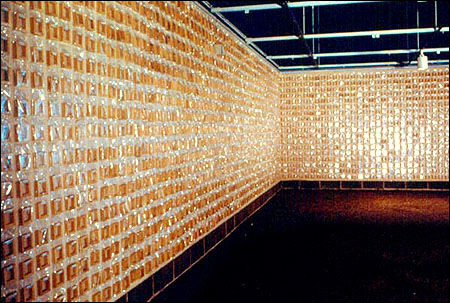

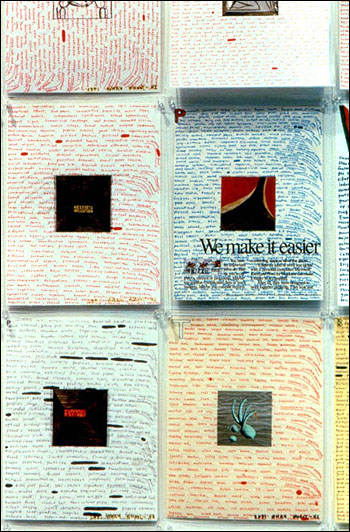

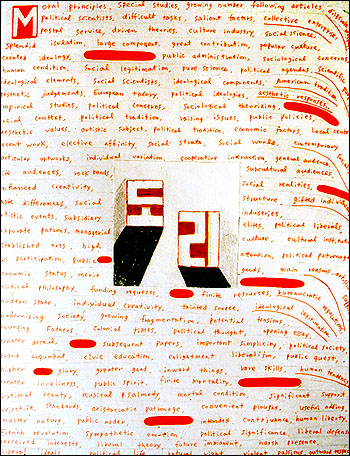

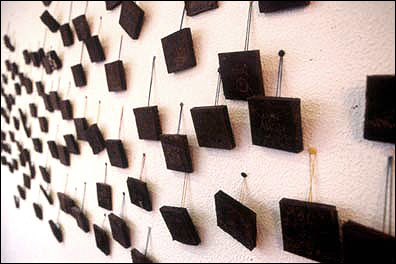

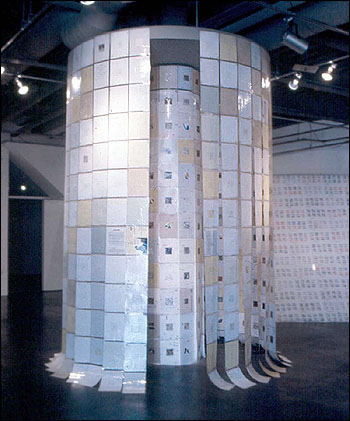

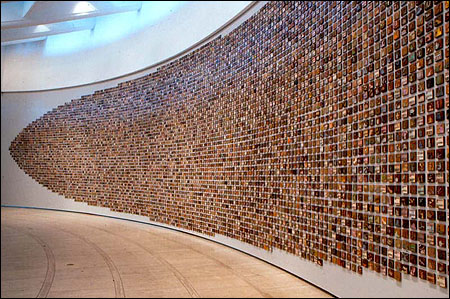

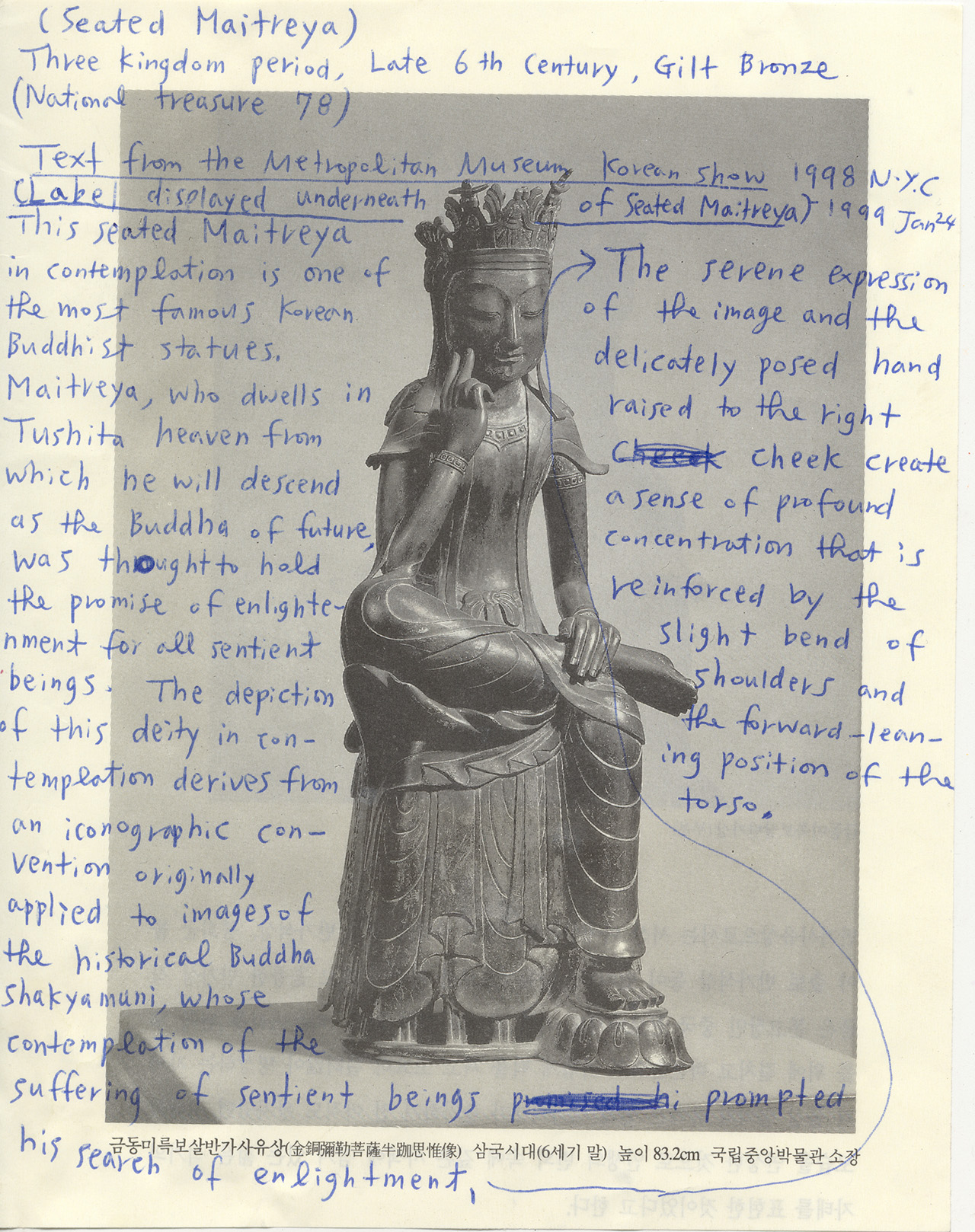

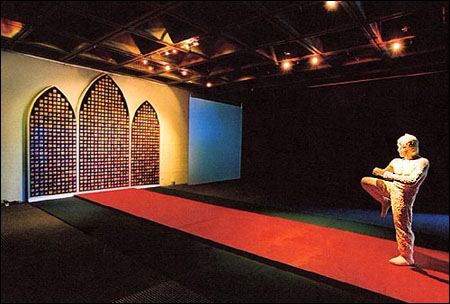

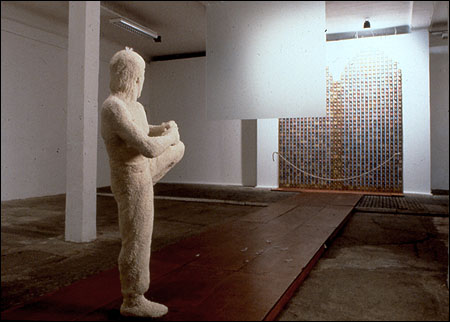

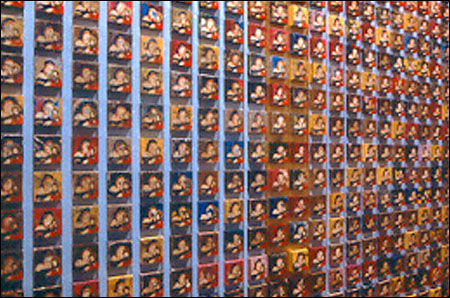

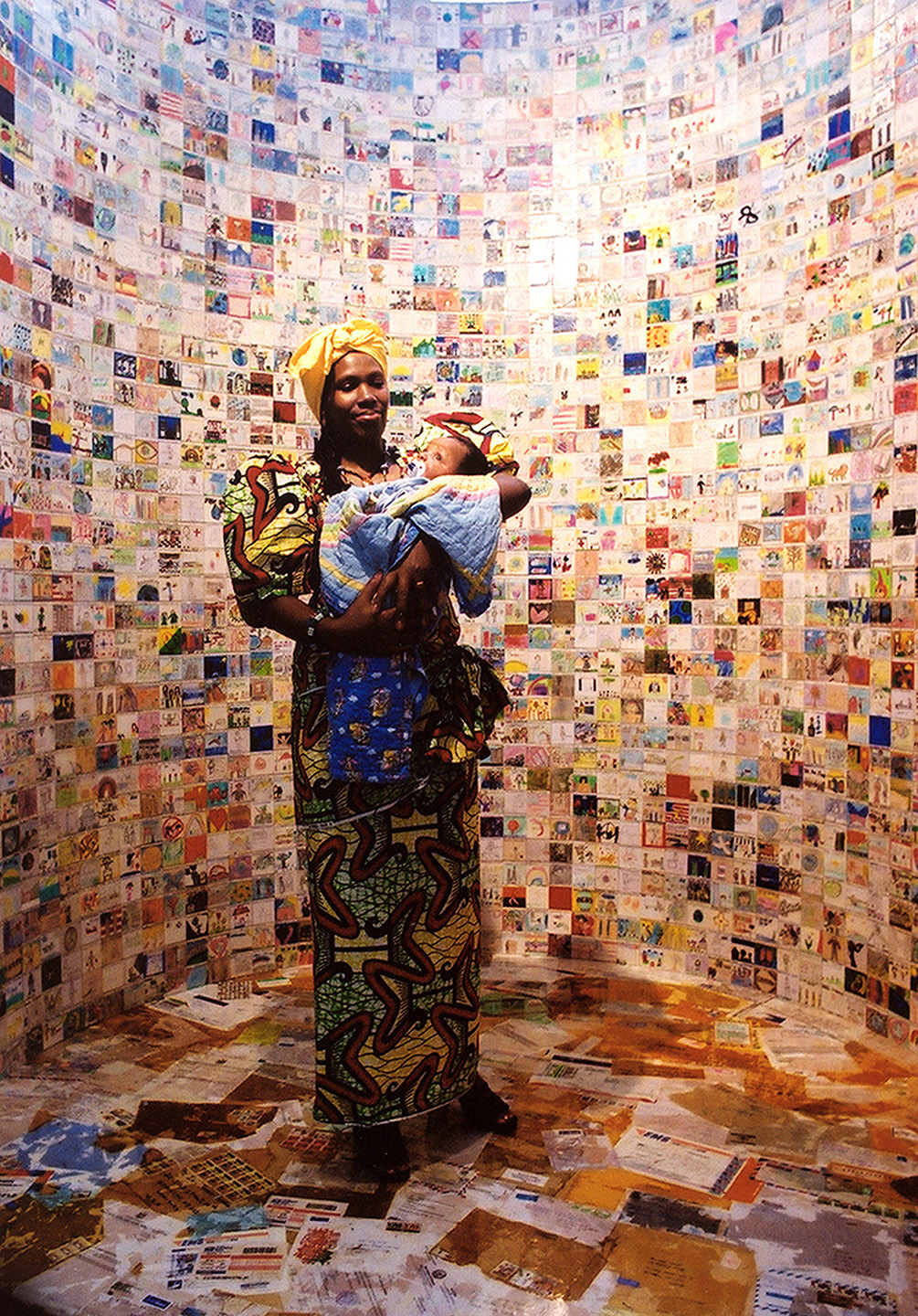

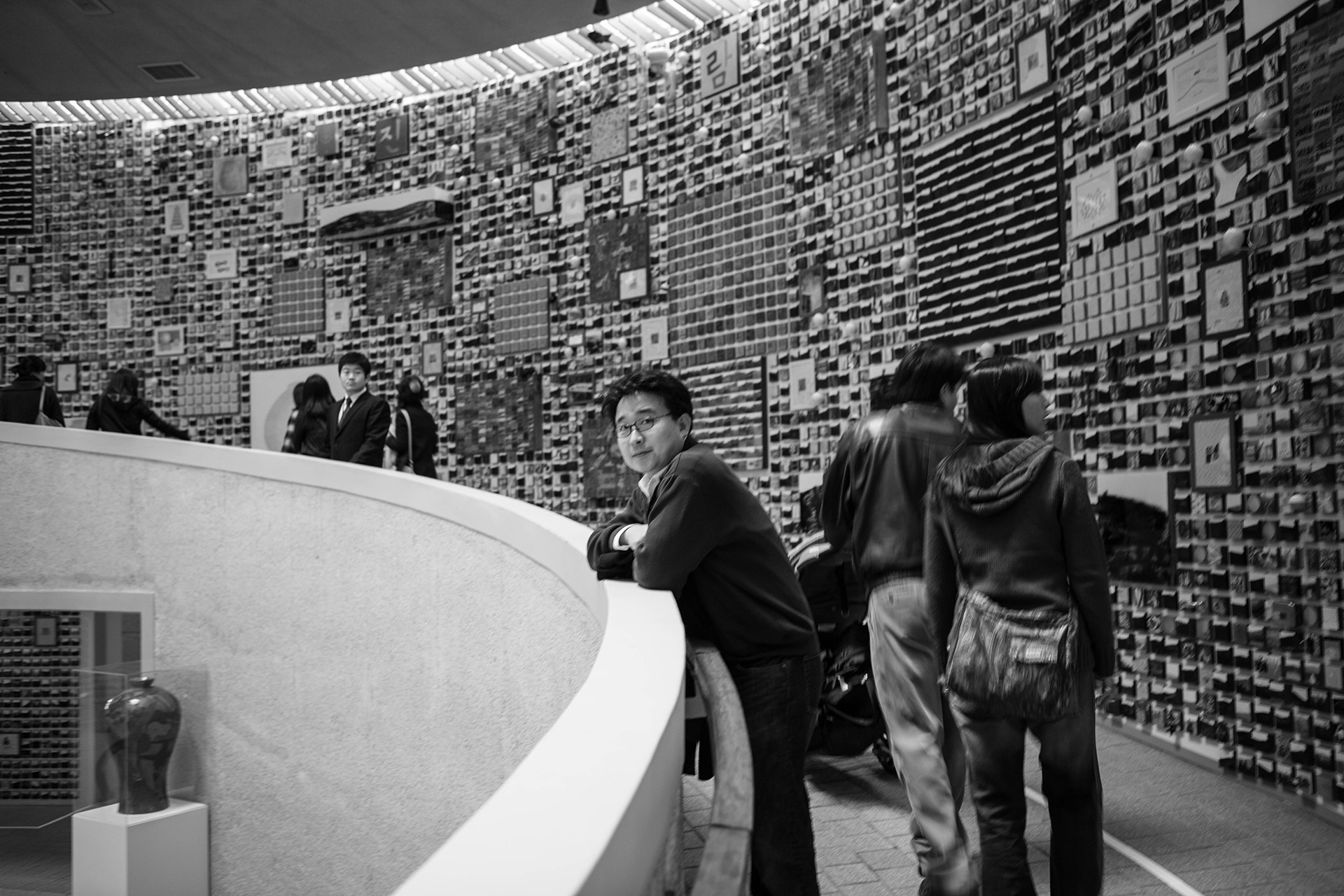

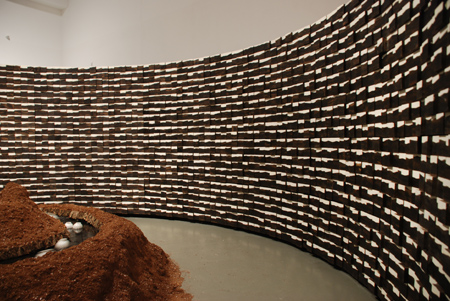

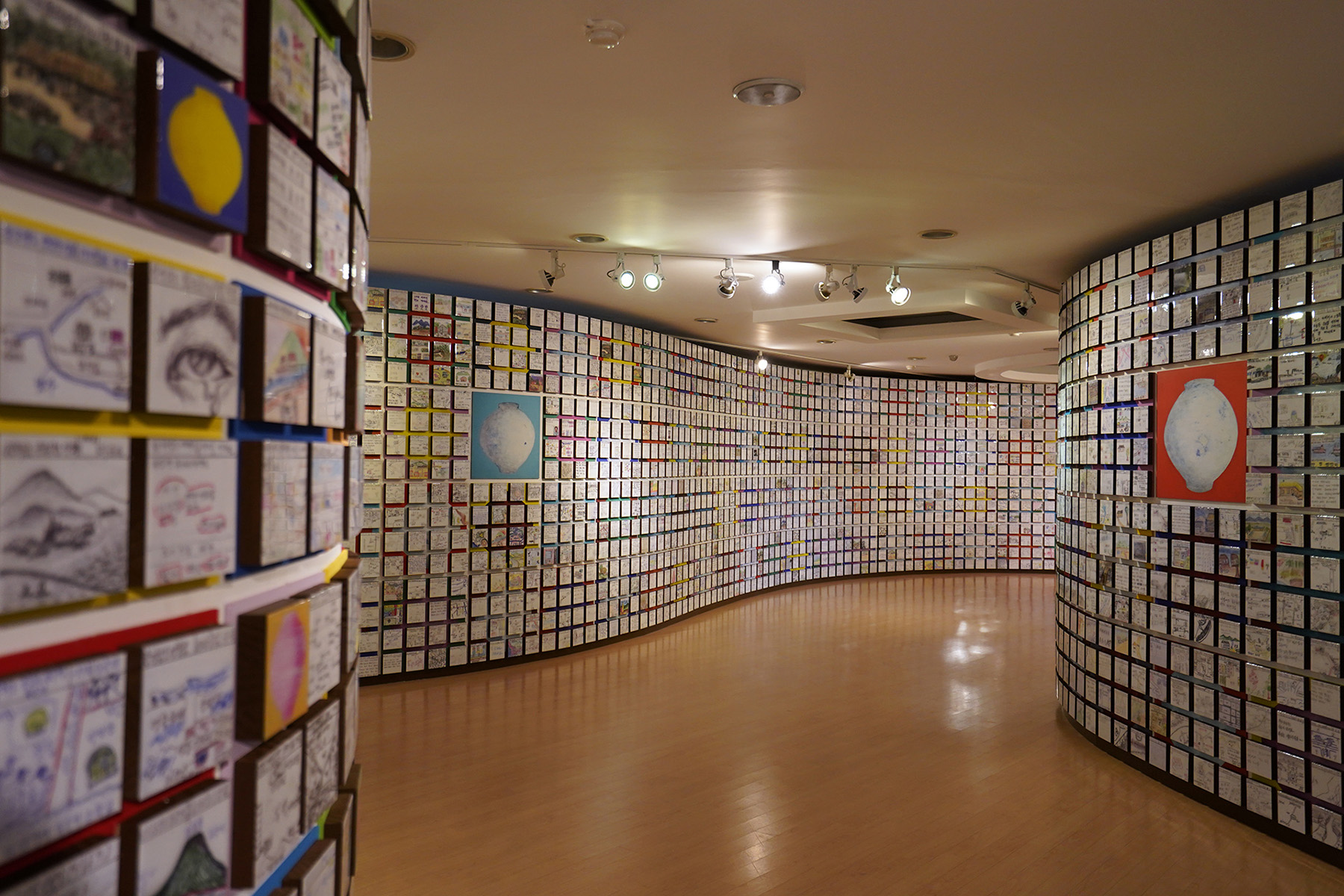

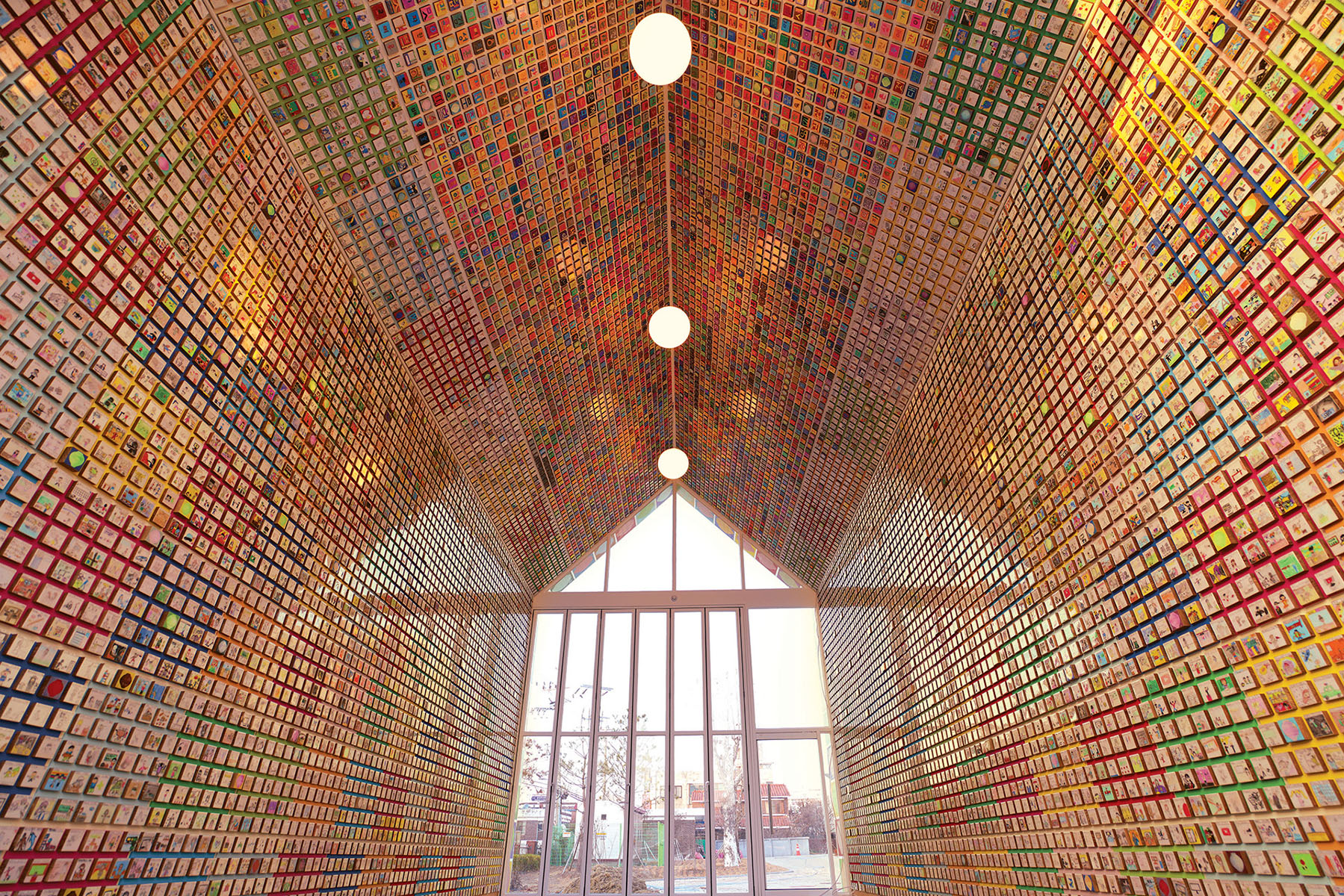

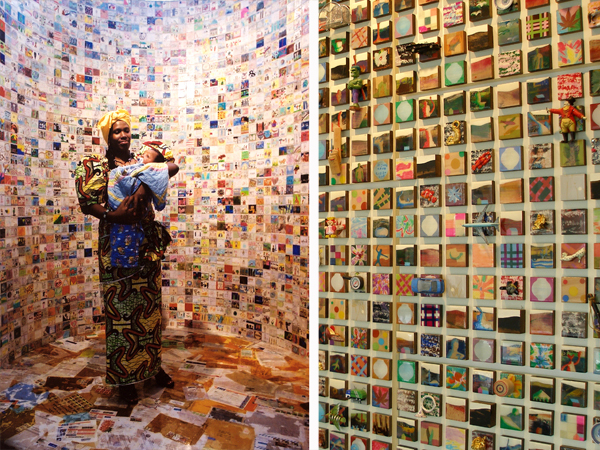

Buddha Learning English (1999) at the Museum Ludwig was influenced by Seokguram Grotto in Gyeongju, Korea. The basic layout of the grotto includes an arched entrance, antechamber and a main rotunda. In the middle of the rotunda, the Buddha is seated with a serene expression of meditation and is accompanied by ten statues in various niches along the walls. In Buddha Learning English, there is a curved wall covered from top to bottom with 3,060 jewel-toned paintings, all measuring three-by-three inches, and enclosed therein is a chocolate covered Seated Maitreya, a Korean National Treasure from the sixth century of a seated Buddha. Each canvas bears a different phrase – for example, “developed moment”, “happy wife”, “erotic context” – randomly selected from my daily reading of The New York Times and other newspapers and magazines. The statue rotates slowly on its base, accompanied by the repetitious sound of chanting.

The series of Buddha paintings and installations was developed early in the nineties. In this series, there were thousands of Buddha paintings that had speakers mounted on the back of the canvas. They played sounds of Buddhist monks chanting and my own voice reading English vocabulary. I got the idea of sound coming out of a picture from a Christmas card that I had received, which played Jingle Bells when you open it. Buddha is not just a figure who lived thousands of years ago, but was everywhere and in everyone including myself.

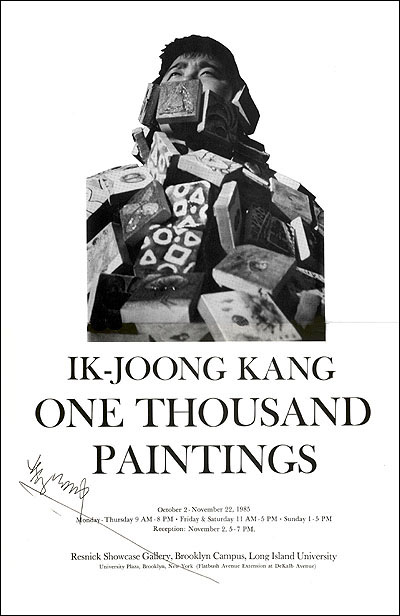

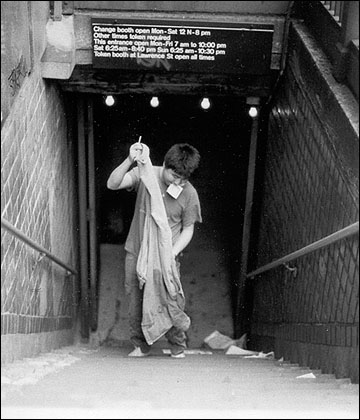

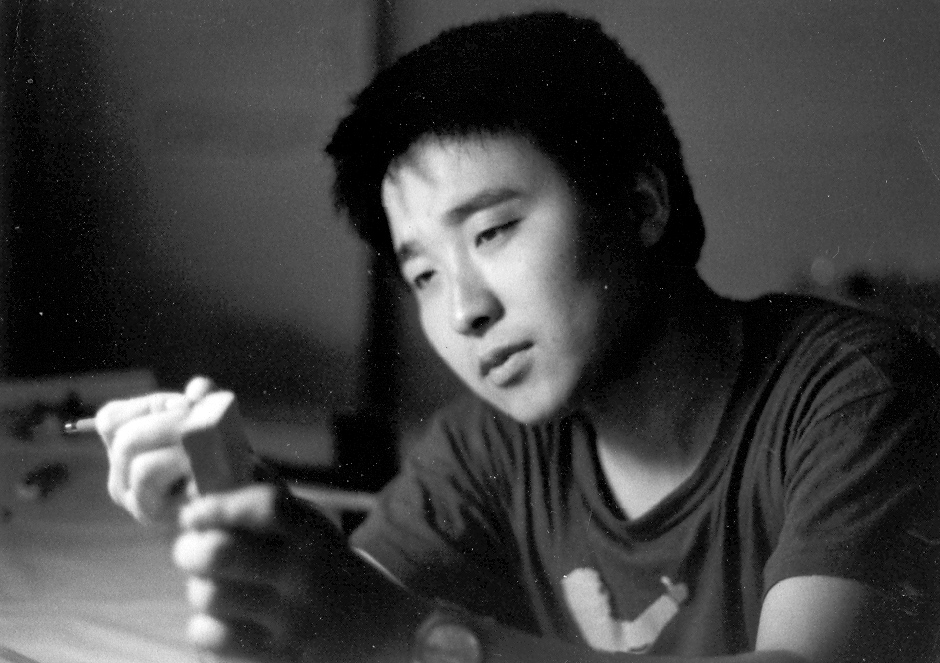

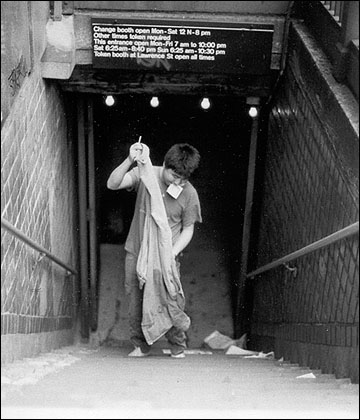

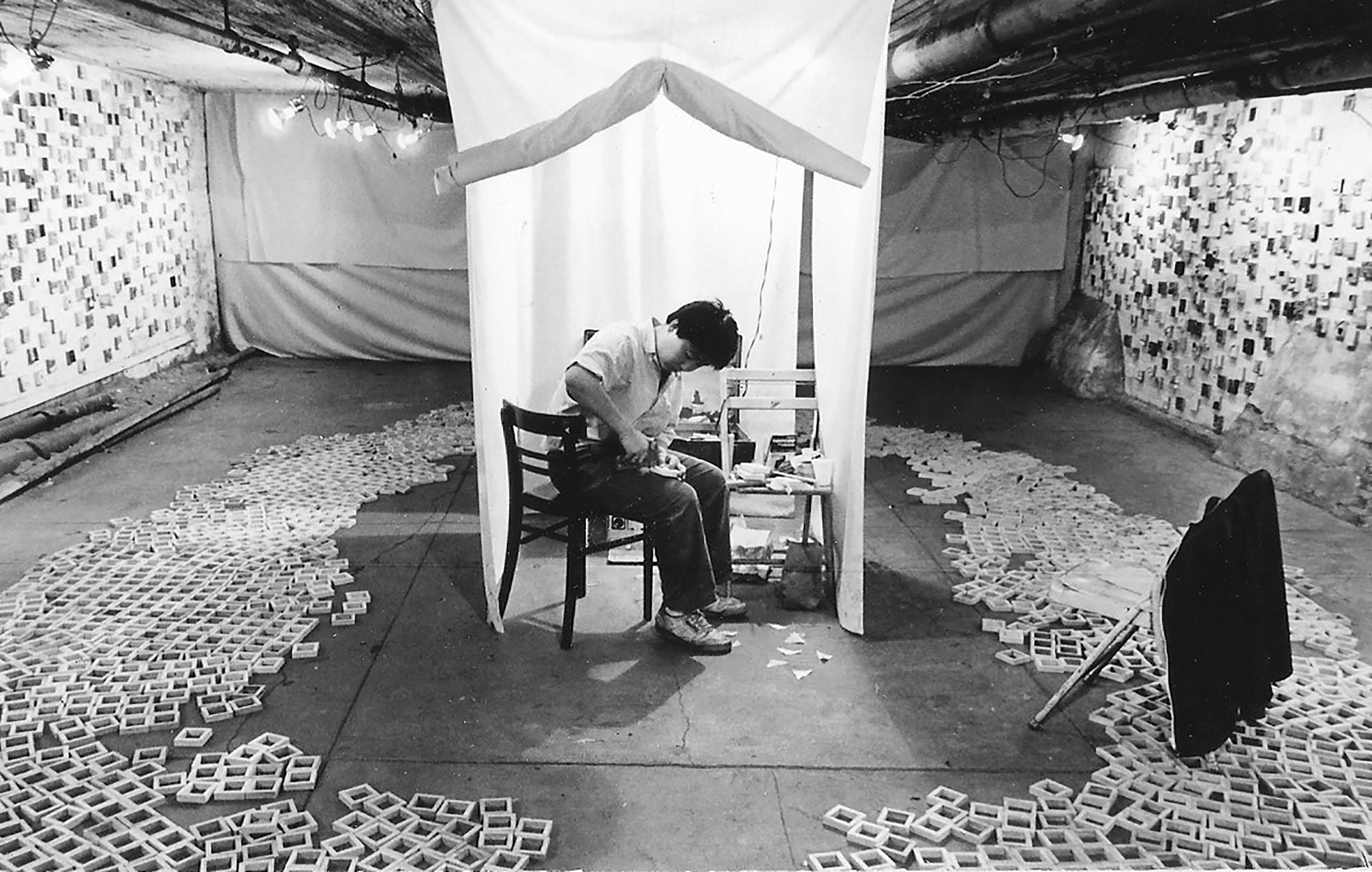

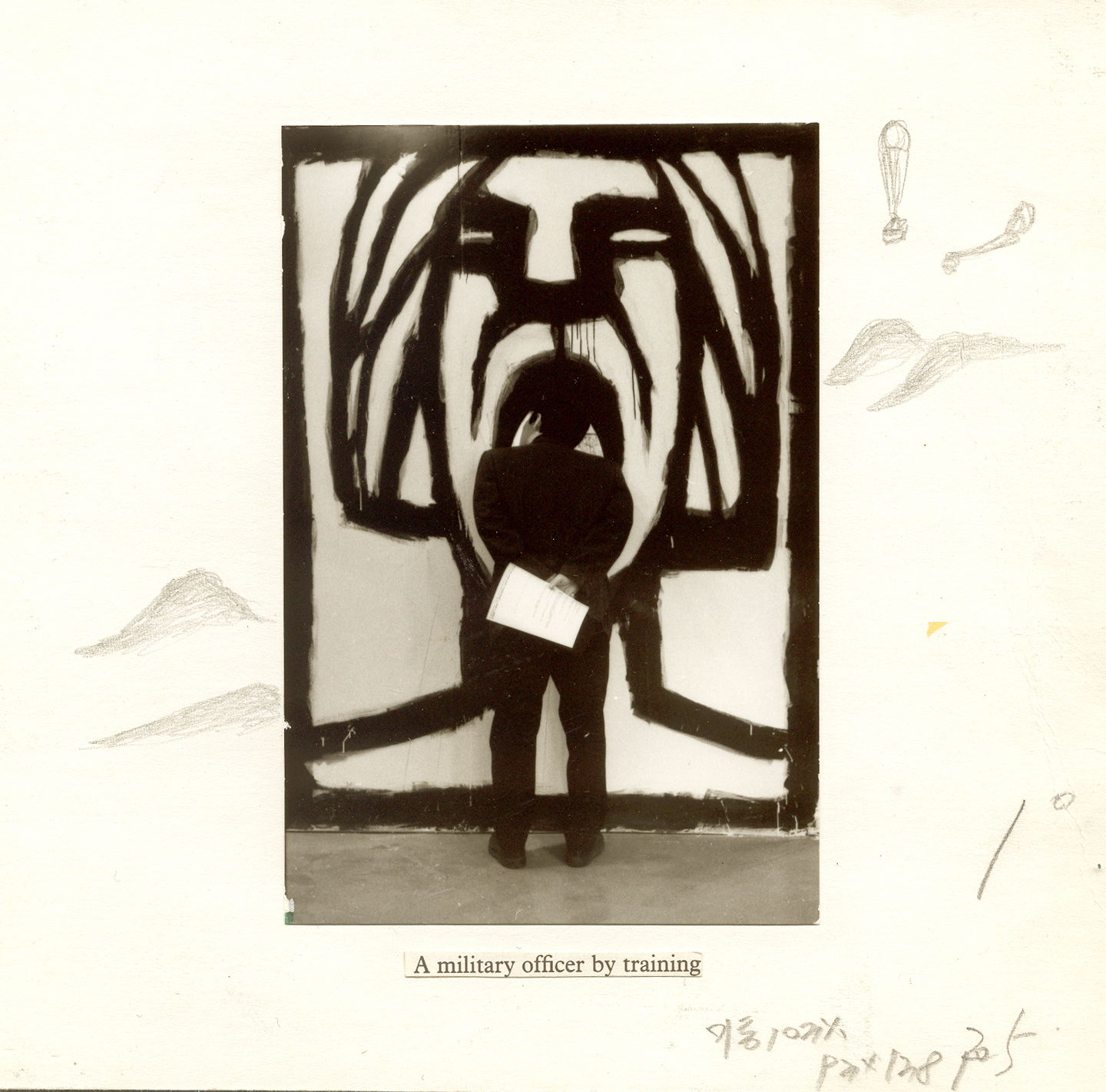

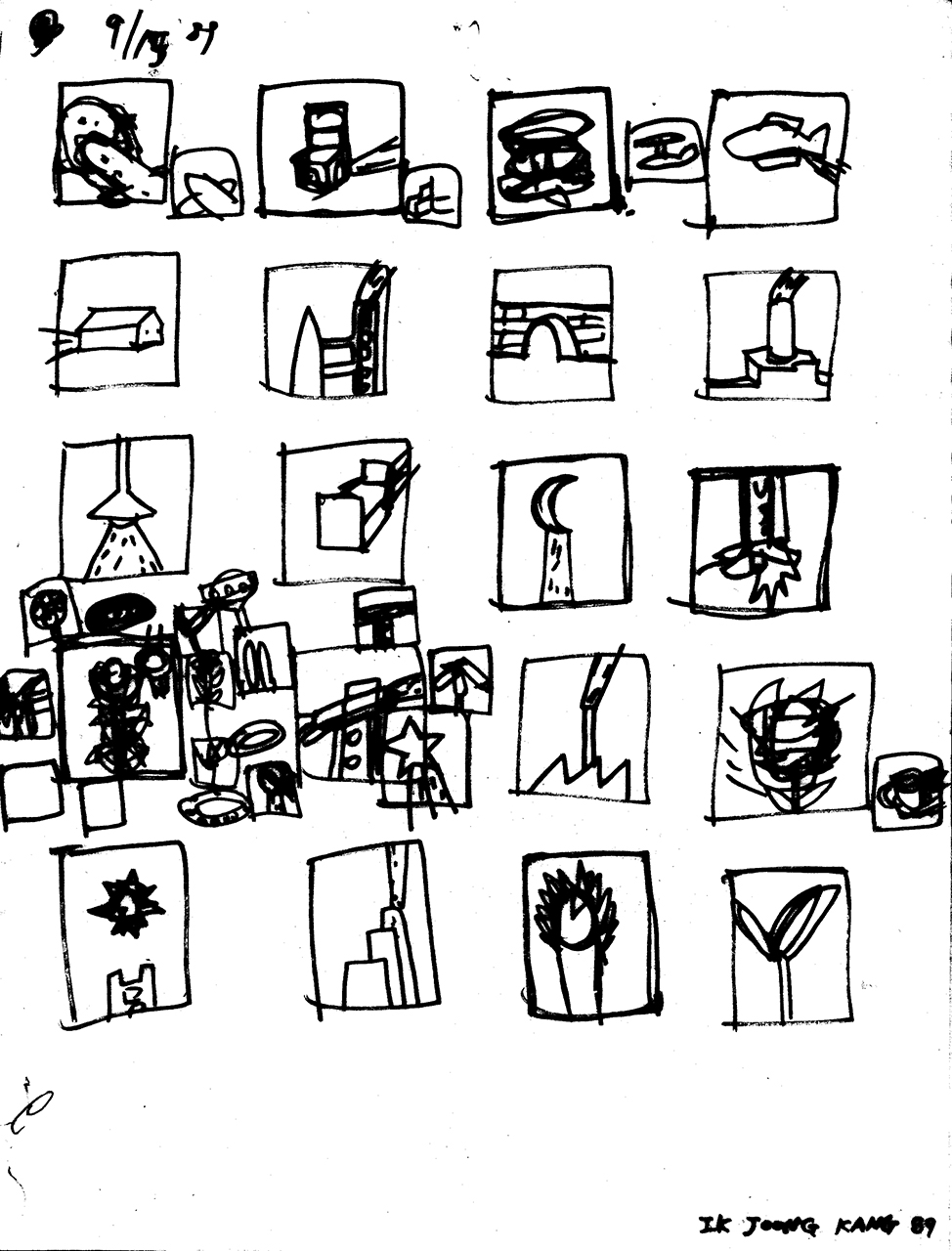

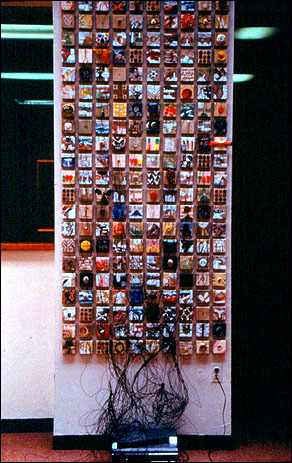

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘One Month Living Performance’ while Kang was at Pratt Institute. Two Raw Gallery, New York, 1986. Image courtesy the artist.

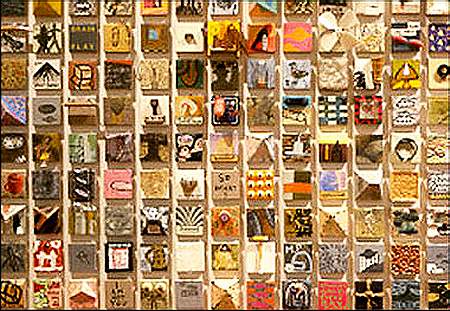

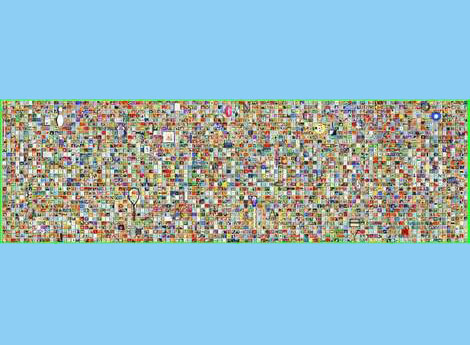

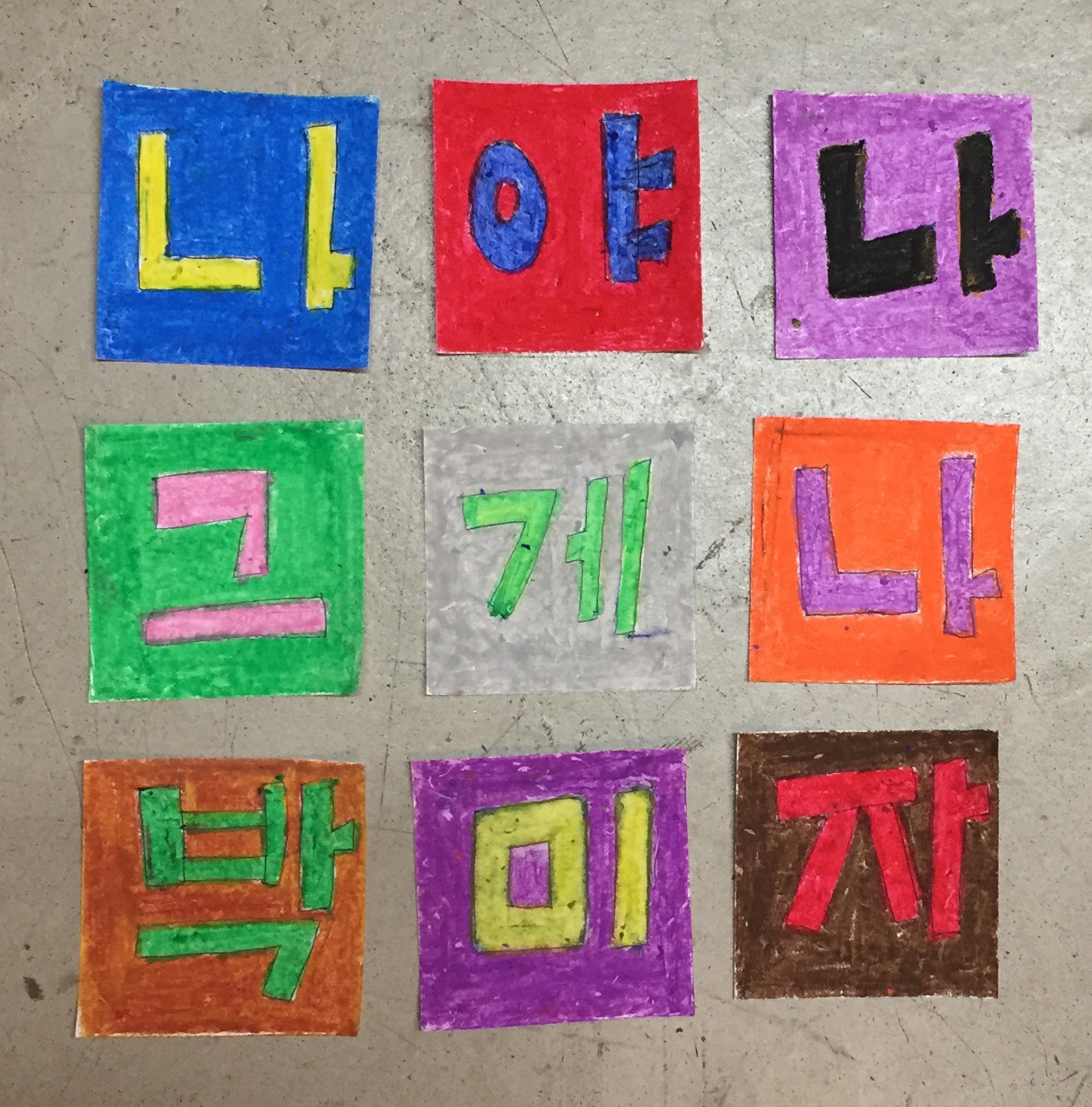

In your artist statement, you’ve written about how working in a three-inch-square format became a part of your daily artistic practice, and how “the idea of making many squares of specific sizes to fit into one screen came about from Zen art. Each screen containing many squares provokes one to be contained in one small square and at the same time within a bigger space … through the small ‘perfect’ space, one can experience a whole new world that is different from the broad world which actually exists.” Could you elaborate on this and how it relates to your work today?

I developed the three-inch-by-three-inch format during my days as a graduate student at the Pratt Institute in New York. I worked on this series primarily outside the classroom. I was poor at the time, working between two jobs at a flea market in Queens and a deli in Manhattan. I needed to find a way to fit art into my lifestyle and the solution was the three-by-three canvas.

I discovered that a small canvas could easily fit into my pockets and into the palm of my hand. And best of all, it was affordable. My lengthy commute transformed into a mobile studio, allowing me time to work. When I first started, my goal was to transform the doodles into large canvases if and when I had some money, [but] as one small canvas accumulated into hundreds and soon thousands, I realised that it was not necessary to transfer them onto big canvases. What I was making was fun and simple. True Zen.

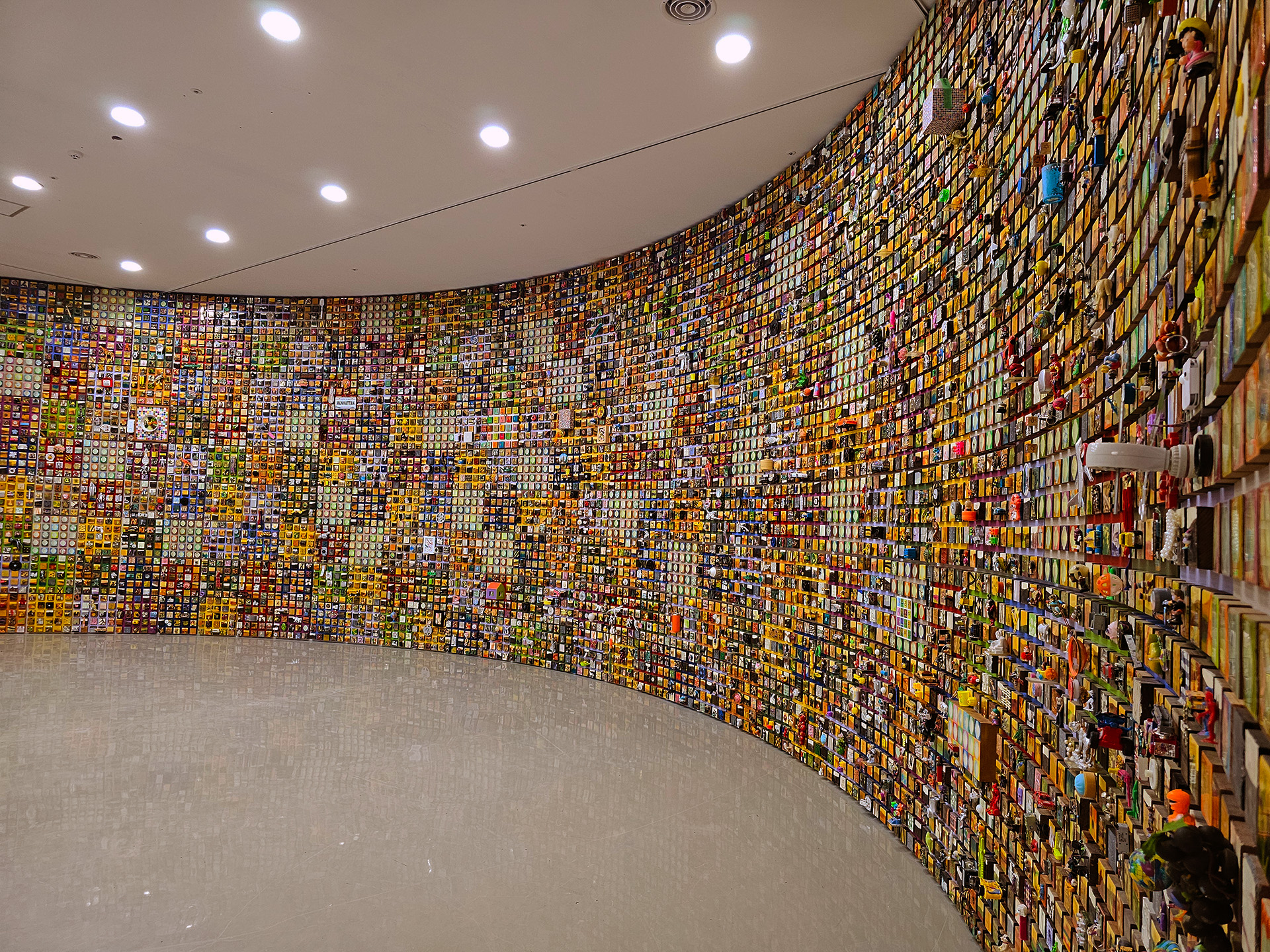

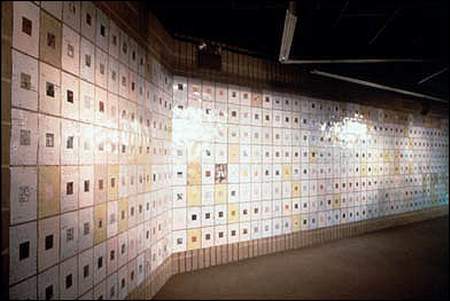

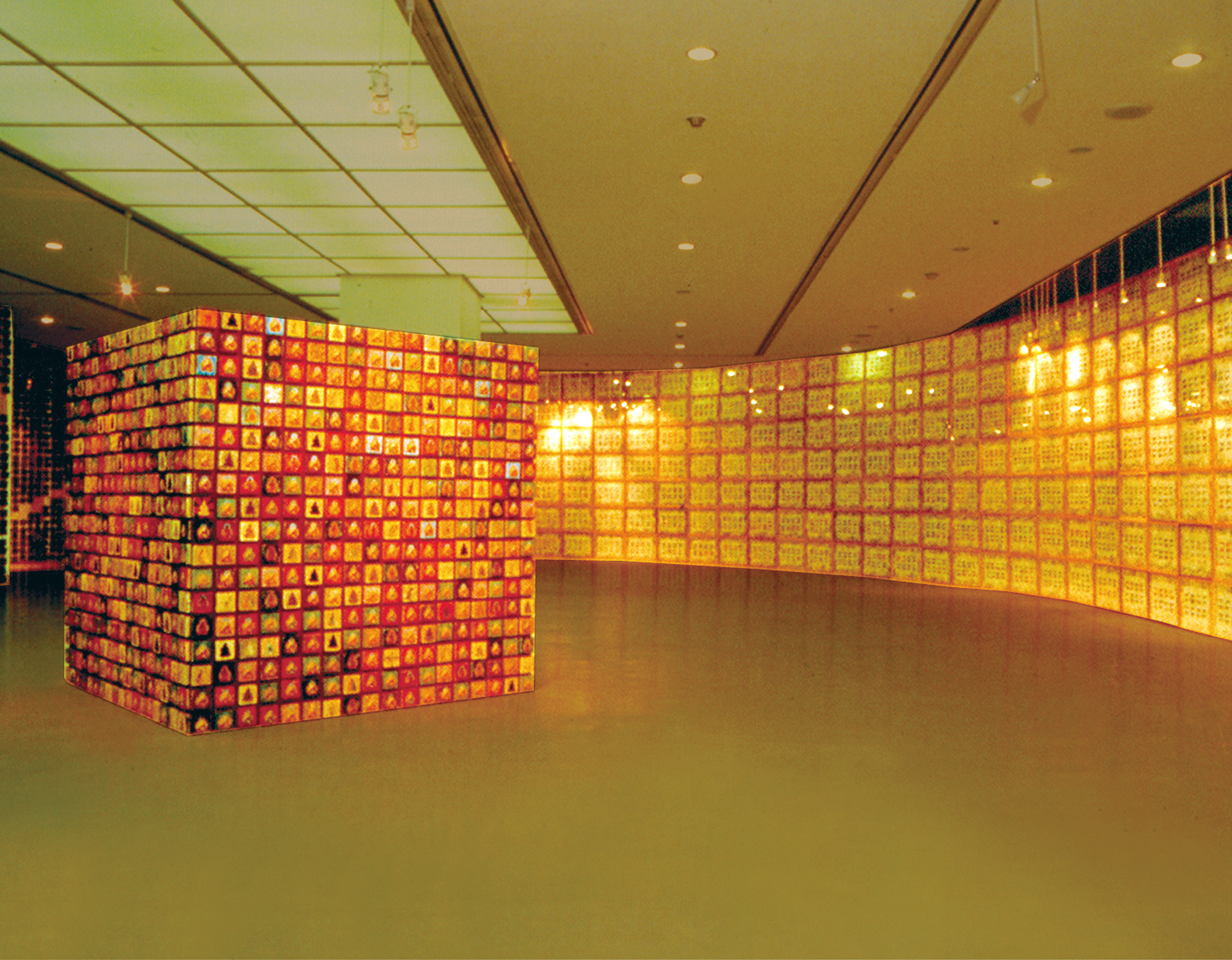

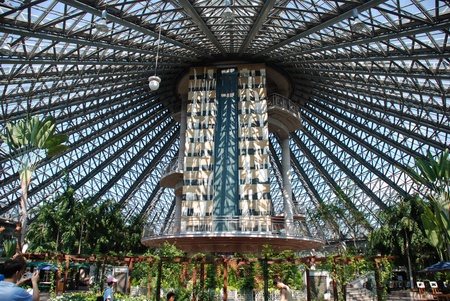

“Multiple Dialogue Infinity”, Ik-Joong Kang with Nam June Paik at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Korea, 2009-2010. 62,000 works, 180 metres. Photo by In Sub Shin. Image courtesy the artist.

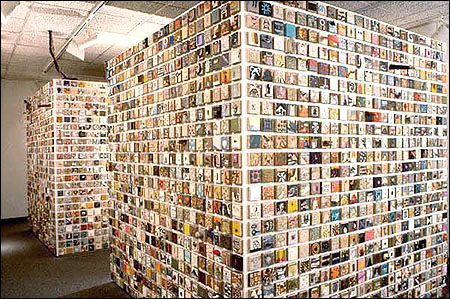

62,000 three-inch-square canvases were shown at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Korea in 2009, under the title “Multiple Dialogue Infinity”. My installation, Smaramansang, surrounded a gigantic tower consisting of 1,003 television monitors, [which constituted] The More, the Better, created by Nam June Paik. Samramansang, which means ‘all things in nature’ in Korean, is everything around me and within me. It includes the things I never imagined.

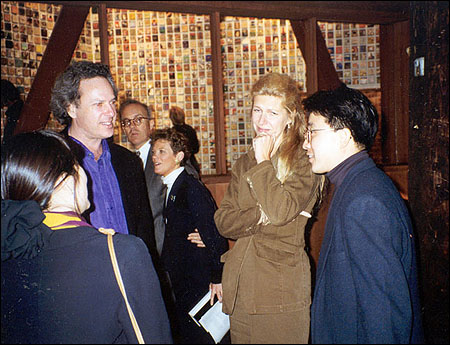

Early on in your artistic career, you participated in an exhibition, Multiple/Dialogue (1994) at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Connecticut with Nam June Paik. Could you talk about this exhibition and how this collaboration came about?

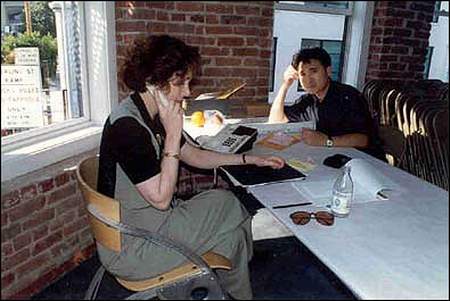

The idea came from the museum’s curator, Eugenie Tsai. She called me when I was in San Francisco working on an installation at the Capp Street Project. She asked me whether I was interested in having a show with Nam June Paik at the Whitney. Without hesitation I said “yes”. While we were preparing the show, Nam June faxed a simple, two-sentence-long message from Düsseldorf in Germany, which read: “I am very flexible. It is very important that Ik-Joong has the better space.”

After the opening reception, one of Nam June’s patrons who worked in finance invited us to his house in Connecticut. He was astonished and amused at the same time by Nam June’s insightful interpretation of minute-by-minute changes in Wall Street. Nam June knew who was fired and who was hired. Then Nam June asked us, “What’s going to happen in the thirtieth century?” He smiled a childish smile. No one could answer the question, because no one even mentioned the 21st century yet. I thought on the way home, “I am pretty sure he is a shaman who sees stars even in daylight.”

Connecting two Koreas through public installations

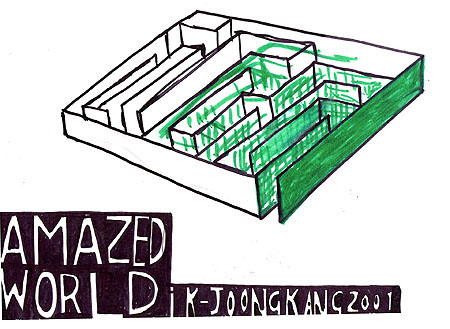

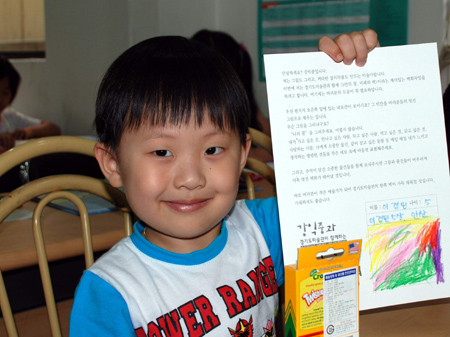

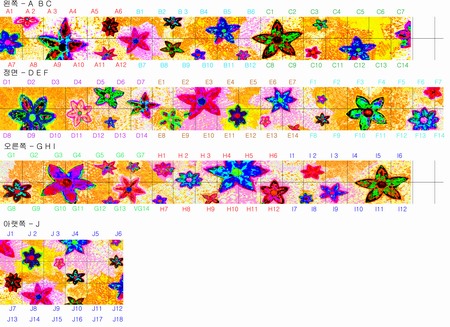

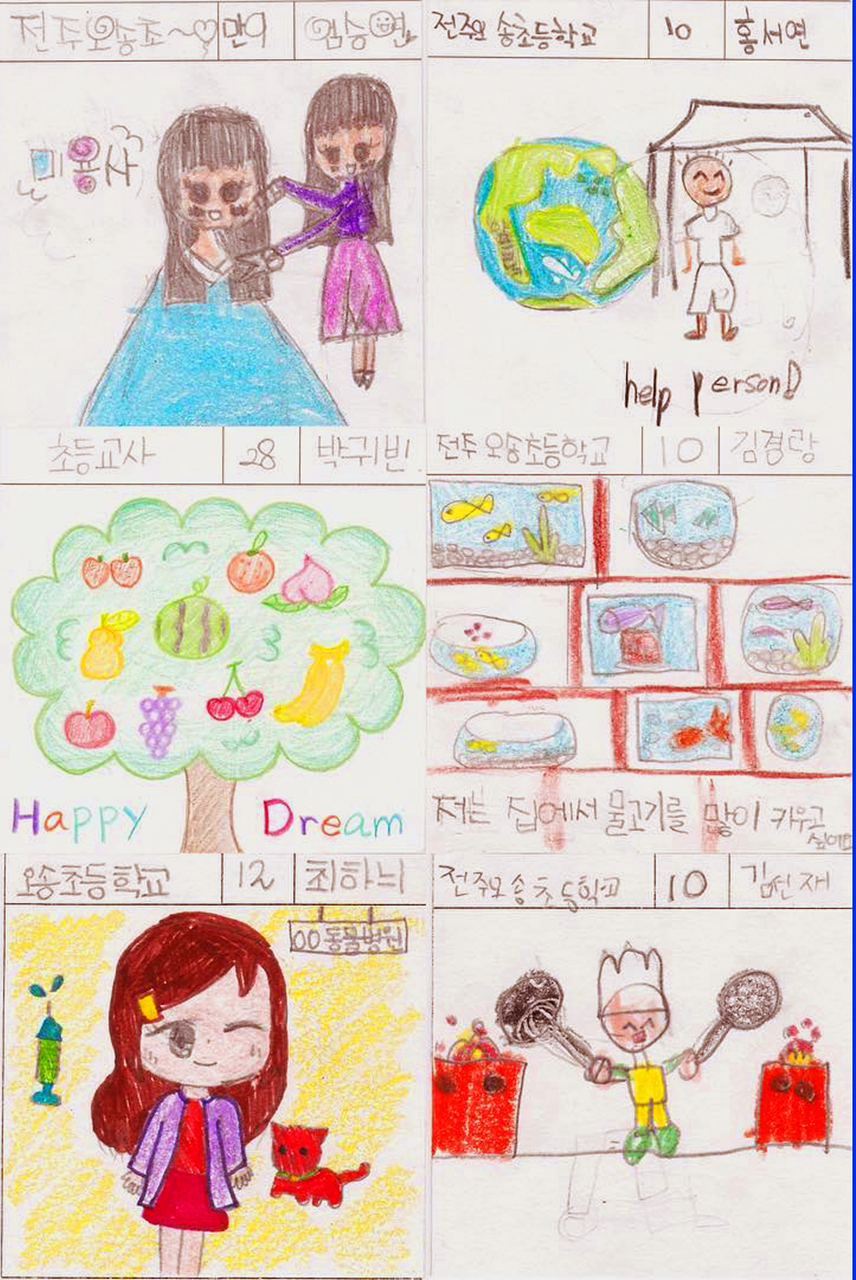

The installations Wall of Hope (2010) for Seoul Asan Children’s Hospital, Moon of Dream (2004), Amazed World (2001-2002) and 100,000 Dreams (1999) are made of drawings from children around the world. What was the inspiration behind these projects?

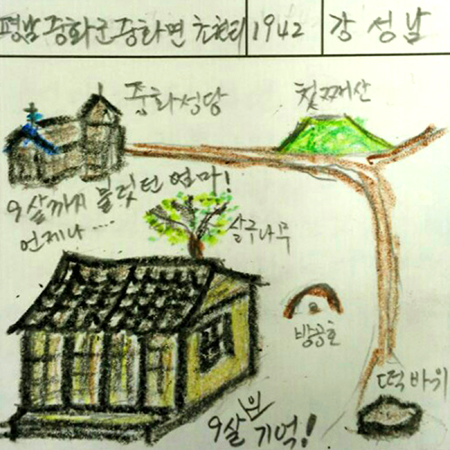

When I was young, I often heard stories from my elders about their lives in a unified Korea, before the war split them apart. I remember how their eyes filled with hope of reuniting once again with their long lost family and friends.

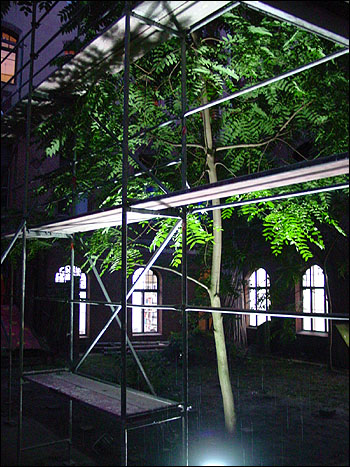

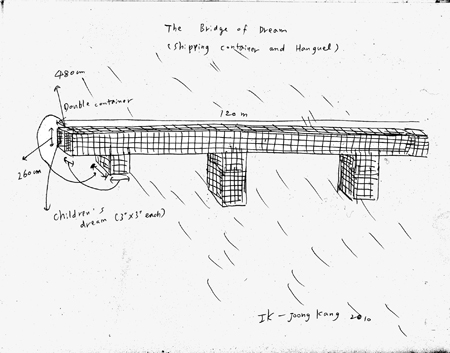

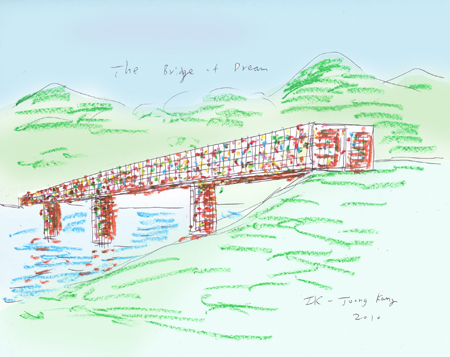

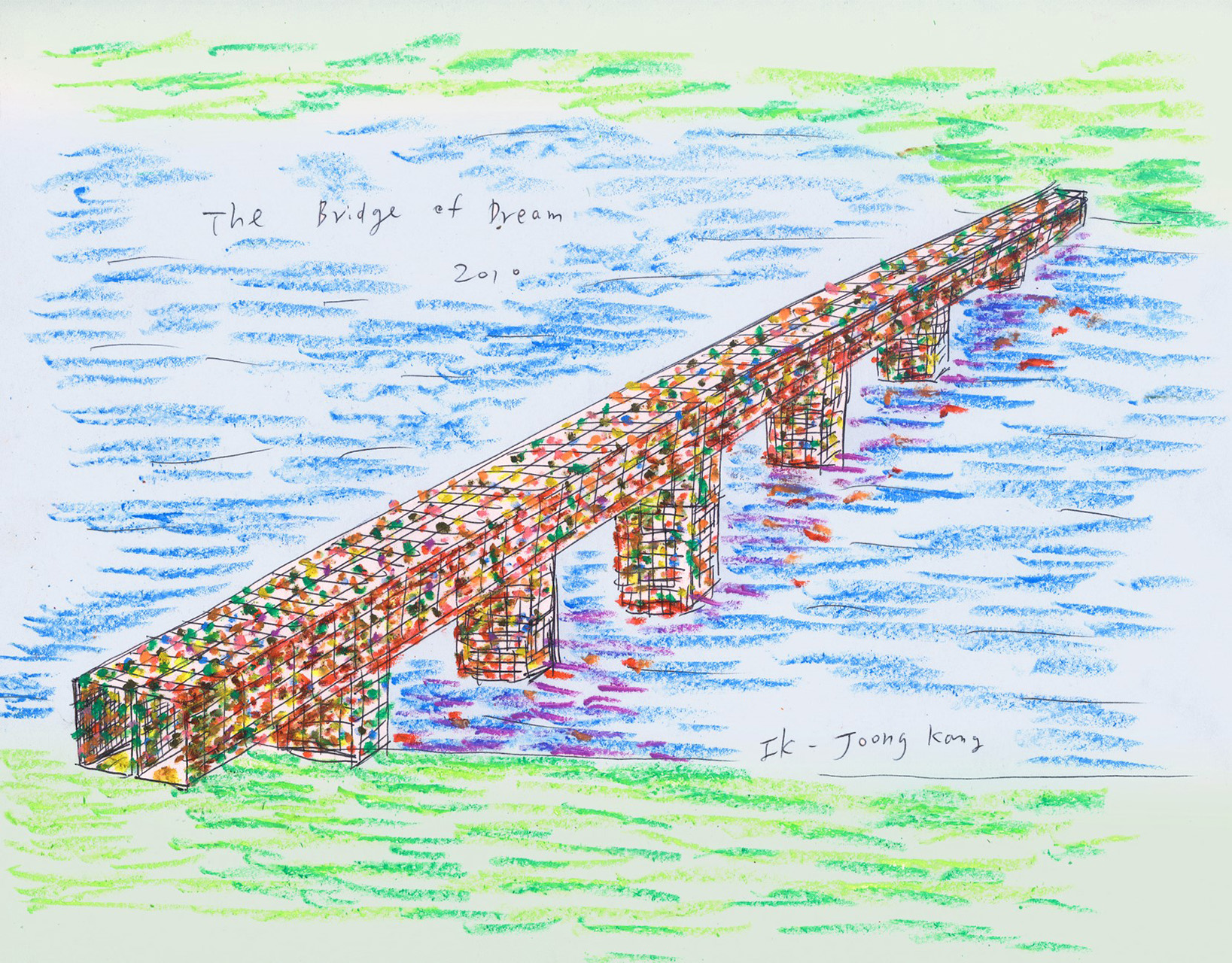

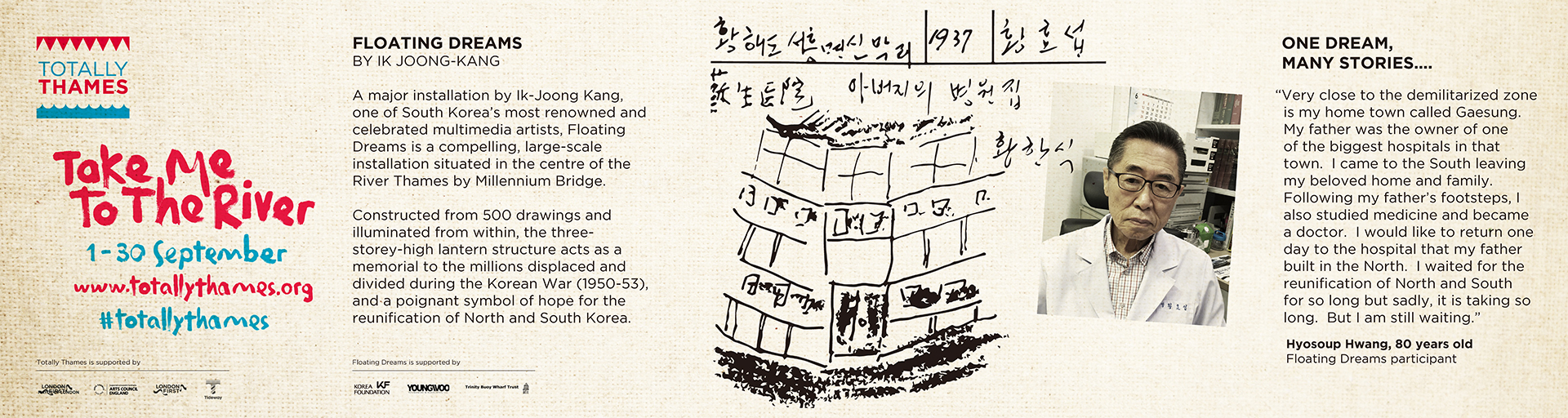

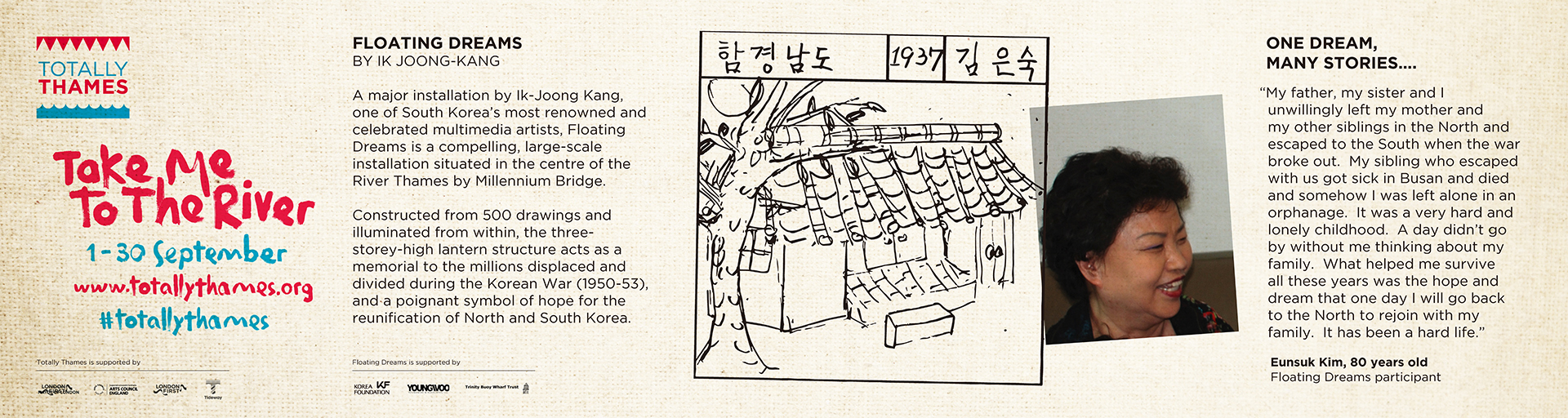

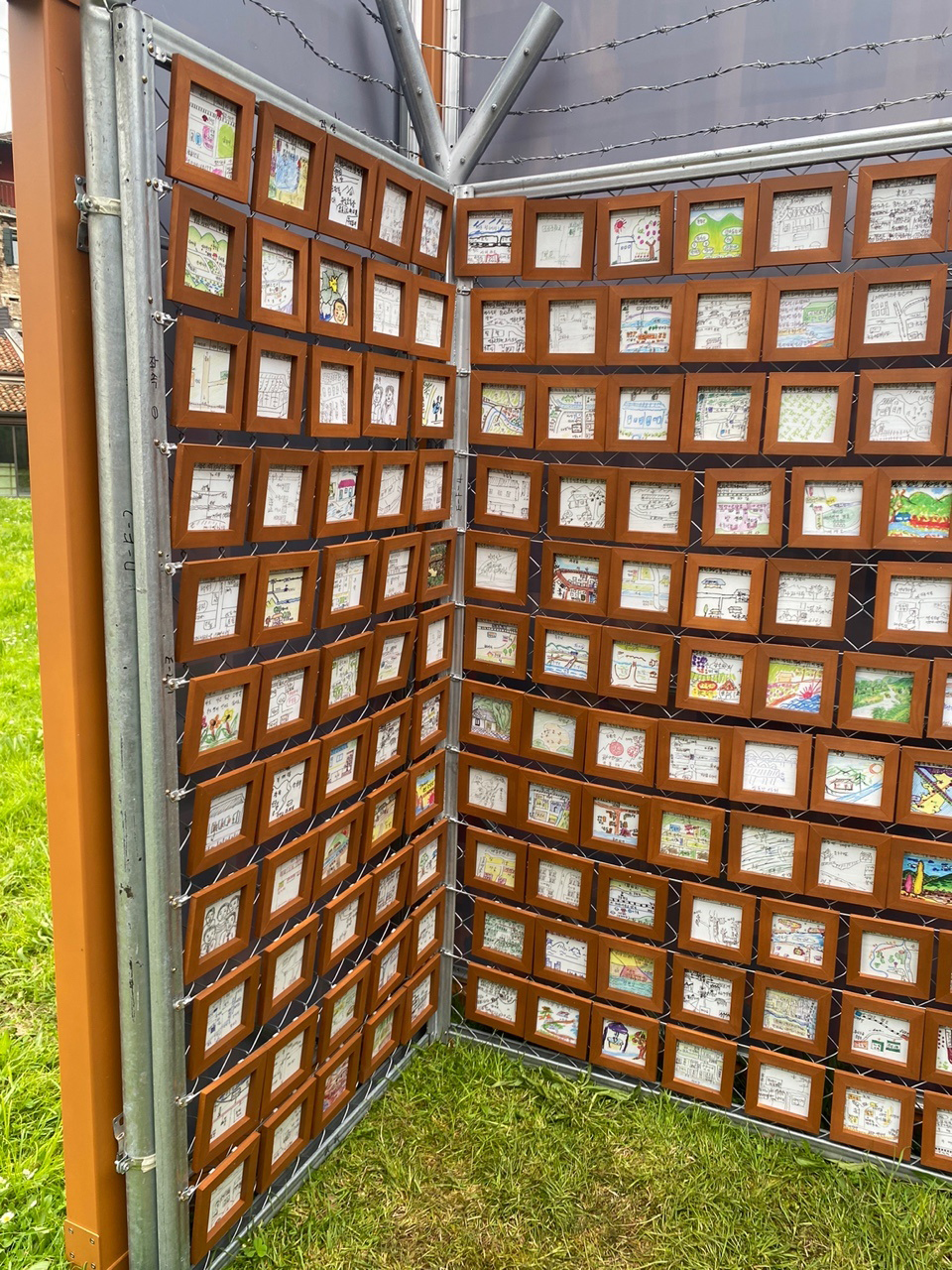

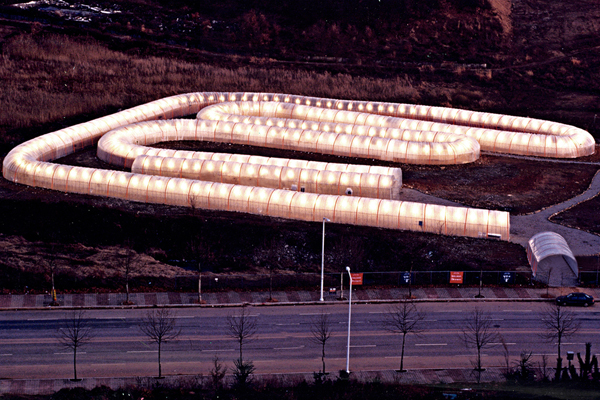

I started collecting drawings by children from 1997, a year before my son was born. With 100,000 Dreams (1999-2000), I was trying to connect the divided country by children’s dreams. 60,000 drawings from South Korea were displayed inside a one-kilometre-long greenhouse near the DMZ border between North and South Korea. The plan was to collect the children’s drawings from both Koreas – but in the end only the works of South Korean children were installed. This project grew into Moon of Dream (2004), Amazed World, Happy World (2005) and other projects. 100,000 Dreams inspired me to build an actual bridge, The Bridge of Dream, over the Imjin River, connecting North and South Korea.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Amazed World’, 2001-2002, 34,000 children’s drawings from over 120 countries, 7.6 x 7.6 cm each. United Nations, New York. Image courtesy the artist.

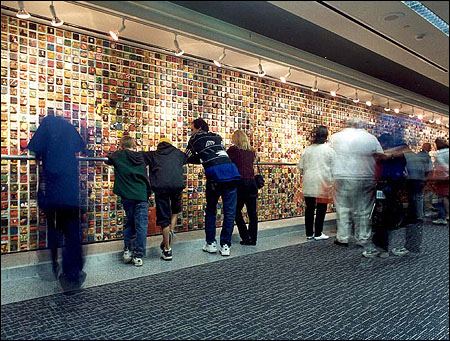

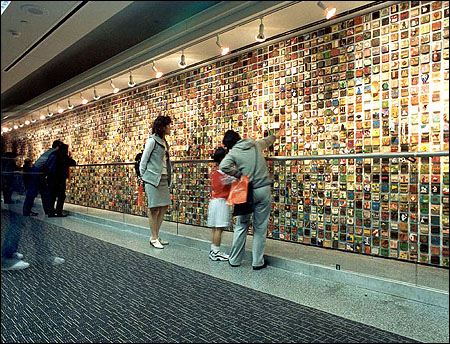

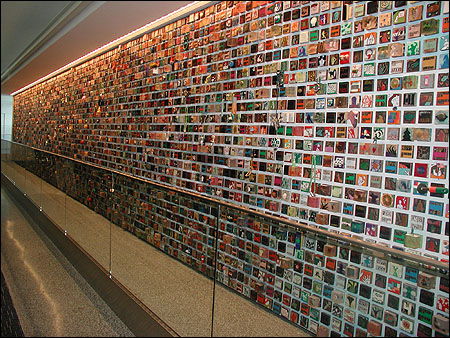

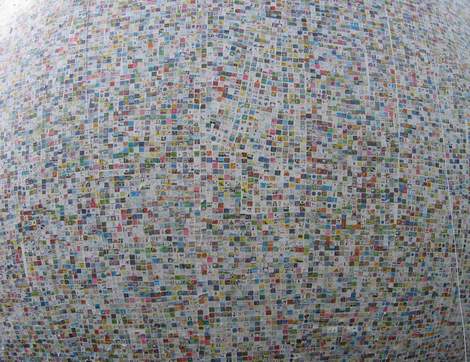

In the visitors’ lobby of the United Nations in New York, nearly 34,000 children’s drawings from over 125 countries are incorporated into Amazed World (2001-2002). The opening of the exhibition was scheduled on 11 September 2001, the day of the bombing of the World Trade Center. Public viewing was postponed in the waves of grief and mourning that engulfed the city.

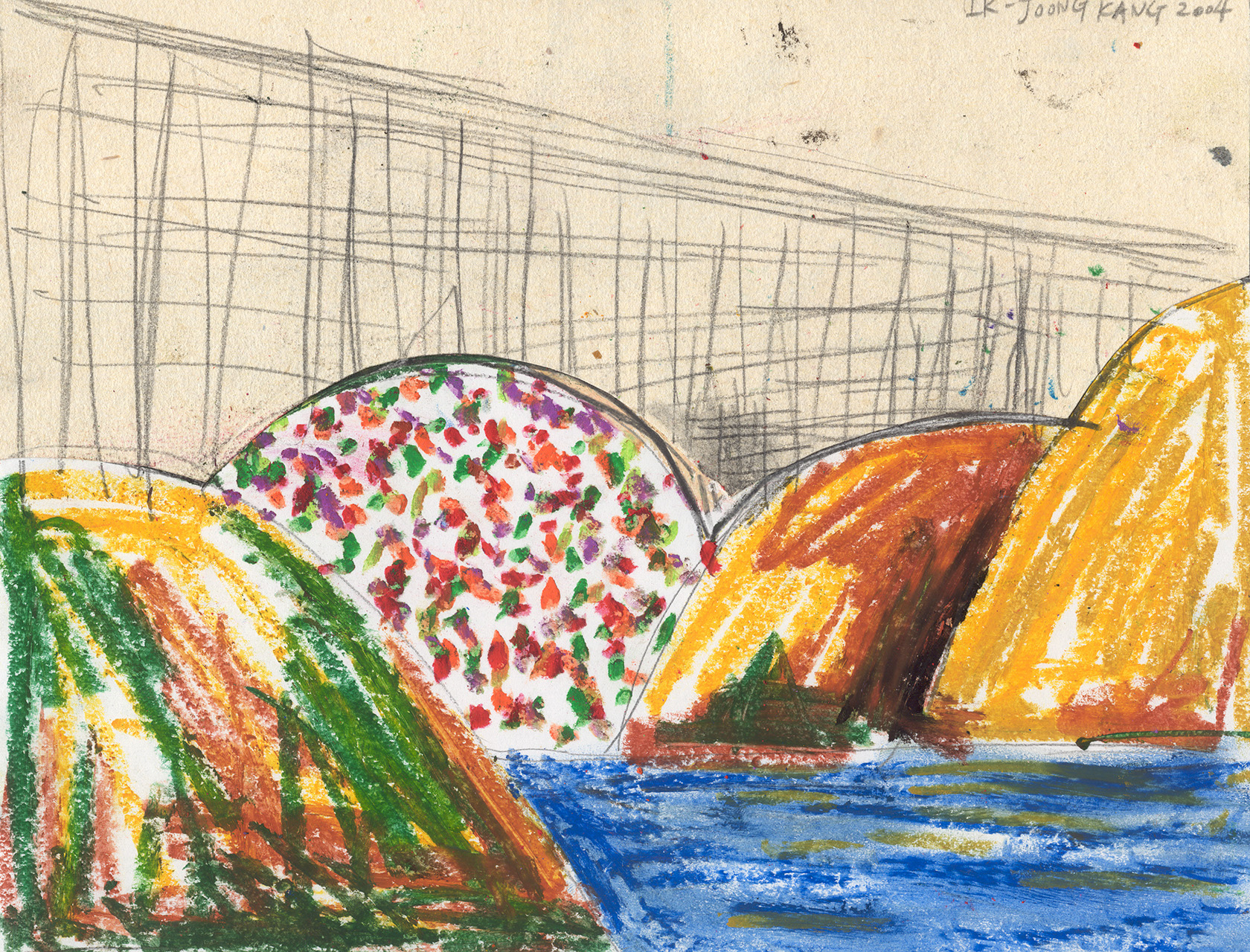

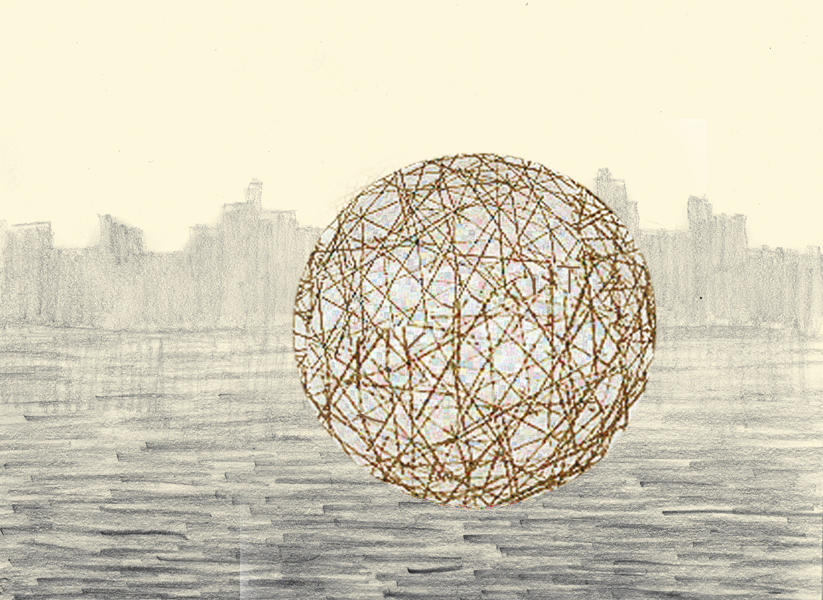

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Moon of Dream’ in progress, 2004, 126,000 children’s drawings from 149 countries, Hosu Park, Korea. Photo by Jeong Yul Lee. Image courtesy the artist.

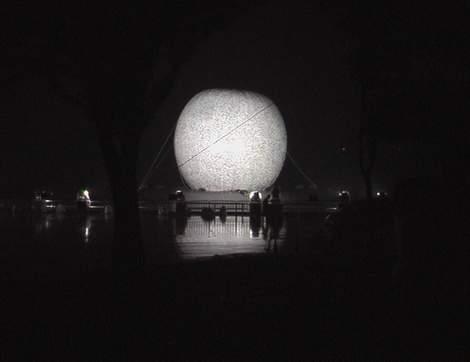

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Moon of Dream’, 2004, 126,000 children’s drawings from 149 countries on vinyl and canvas, globe: 15 metres in diameter, Hosu Park, Korea. Photo by Jeong Yul Lee. Image courtesy the artist.

Moon of Dream, a 48-foot diameter globe with 126,000 children’s drawings, was launched at the lake, not far from the DMZ. In the morning of the opening day, I was shocked to see a somewhat deflated and unbalanced giant globe floating on the water. Apparently, we pumped too much air into the balloon thinking that we could get the perfectly round shape of the globe. But in doing so, the vinyl canvas material of the globe ripped and the full moon shape slowly became an imperfect one.

There was despair at first, but soon I saw a lovely shape in the deflated globe – a moon jar! What made the moon jar so beautiful were the imperfections. It’s imperfection [that] makes perfection.

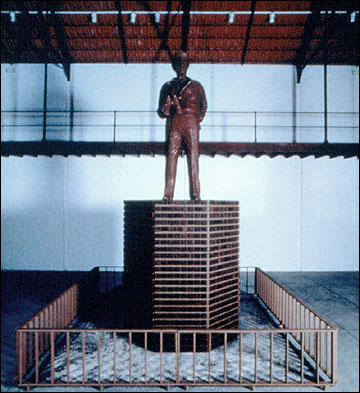

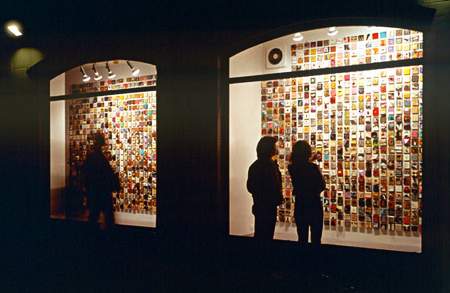

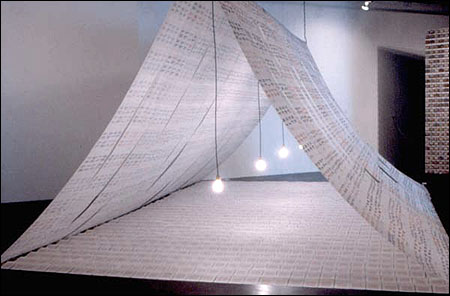

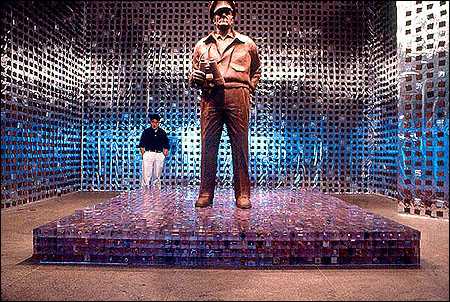

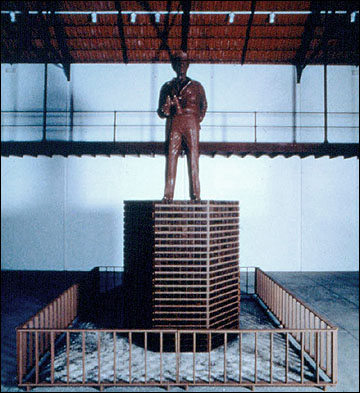

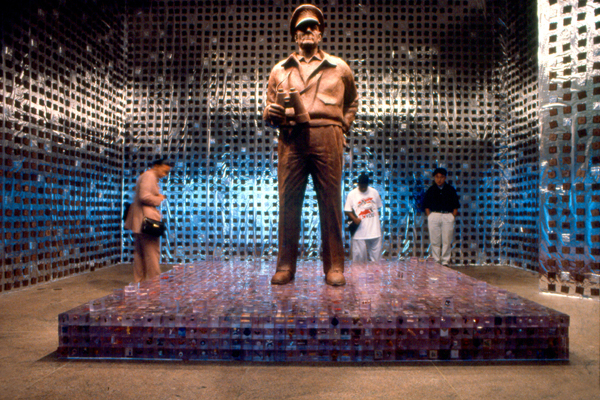

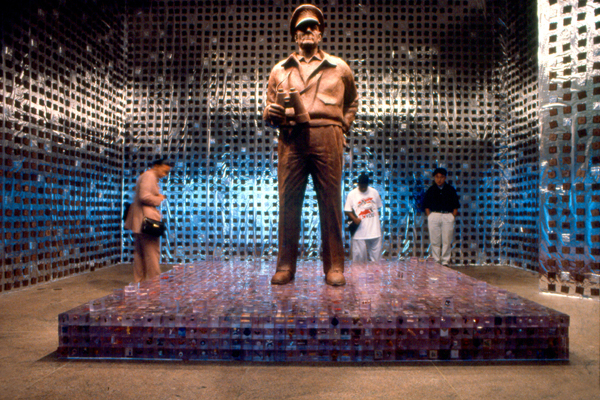

Ik-Joong Kang, ’8490 Days of Memory’, installation, 1997, Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris, New York. Image courtesy the artist.

There is a quantifying and numerical aspect to your works and titles, such as 100,000 Dreams, your three-inch-squared format, 40,000 art panels on the Korean Pavilion, the Moon of Dreams installation made of 126,000 children’s drawings from 141 countries and so on. Could you talk about the importance of numbers in your work?

I’m good at counting and memorising useless numbers. It’s one of those habits I really need to get rid of. I heard that it’s a common practice among prudent people. I find satisfaction in figuring out the number of stories as I pass by a building. How many trees there are from my home to the office. How many lights there are in the Lincoln Tunnel that I drive through about twice a week. Once I’m out of that tunnel, I feel nauseous from all that counting; it’s something that I just do.

But numbers are very helpful in understanding a certain situation or relationship. Like the way numbers can explain the altitude of sound, I believe that there is a definite correlation between the distance of two objects. In this sense, the correlation between my studio to my favourite Chinese restaurant, A-Wah on Catherine Street, can be explained by the number of steps: 722 steps – but only achievable if you can avoid the tourists on Canal Street stopping to ask for directions.

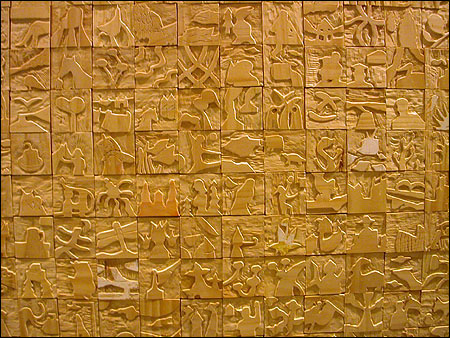

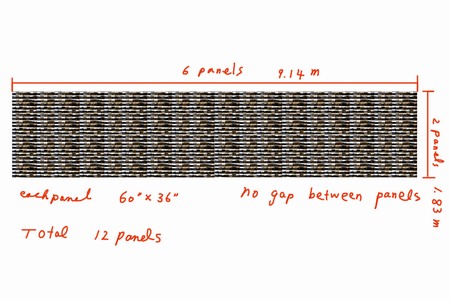

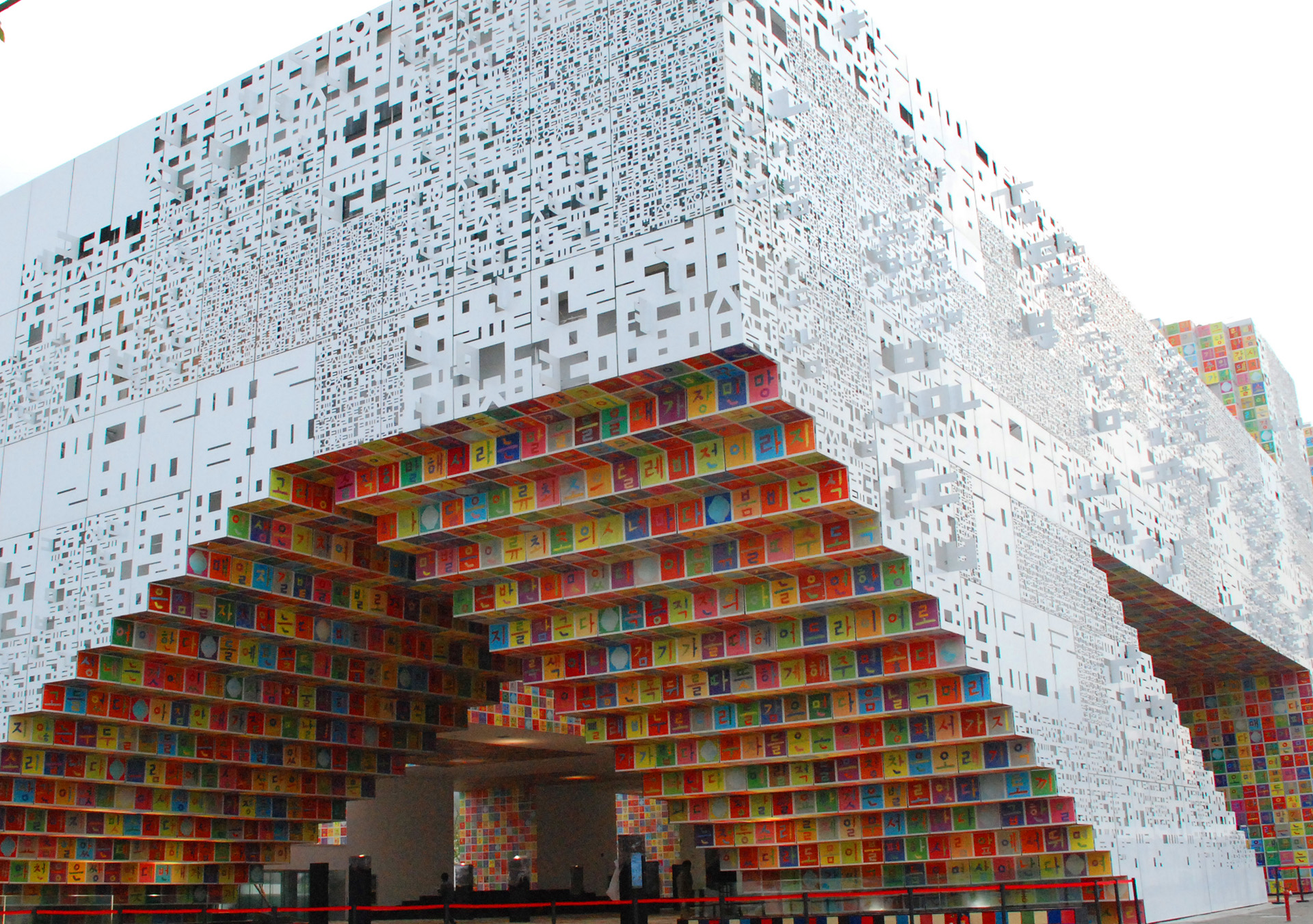

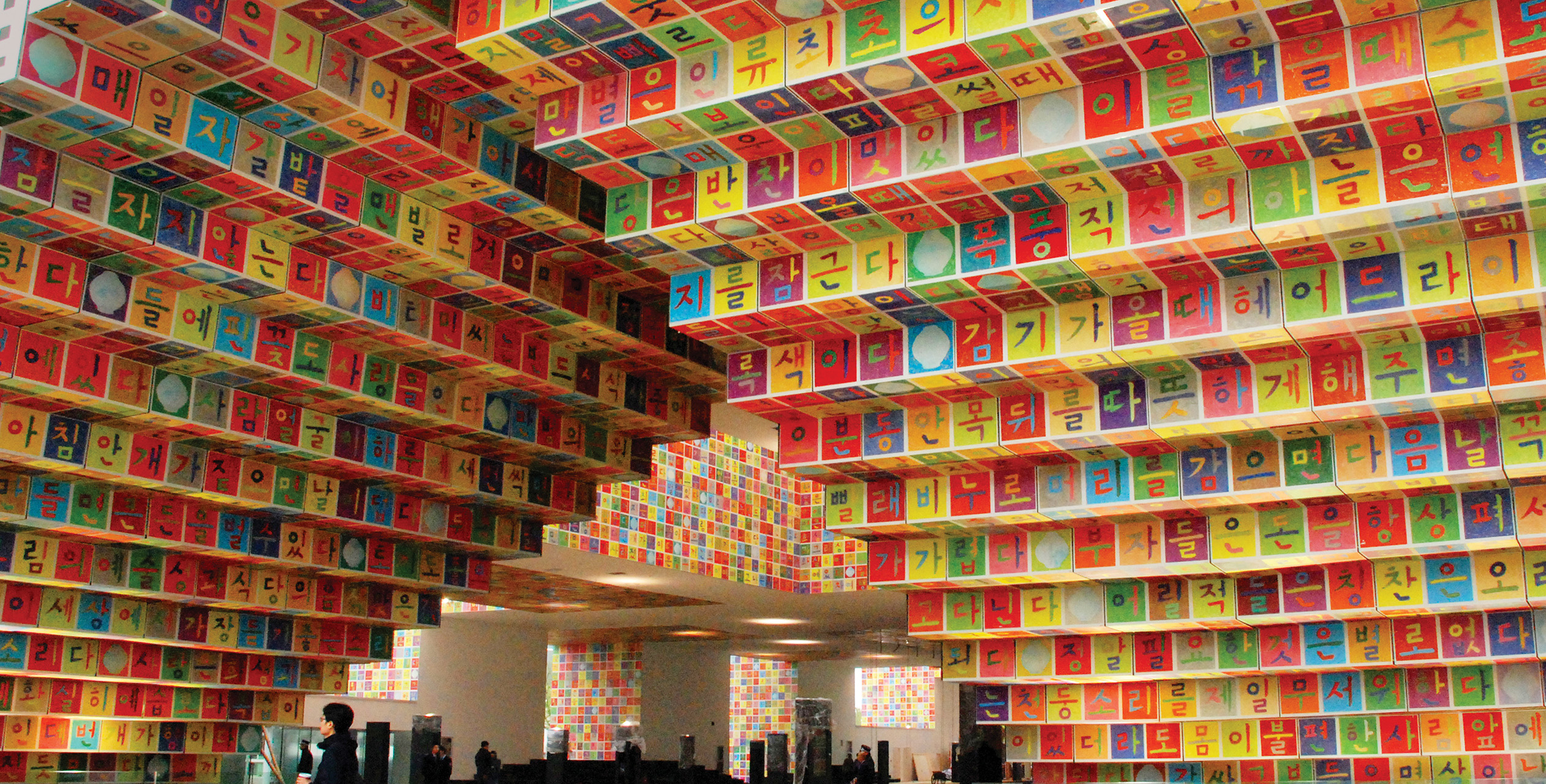

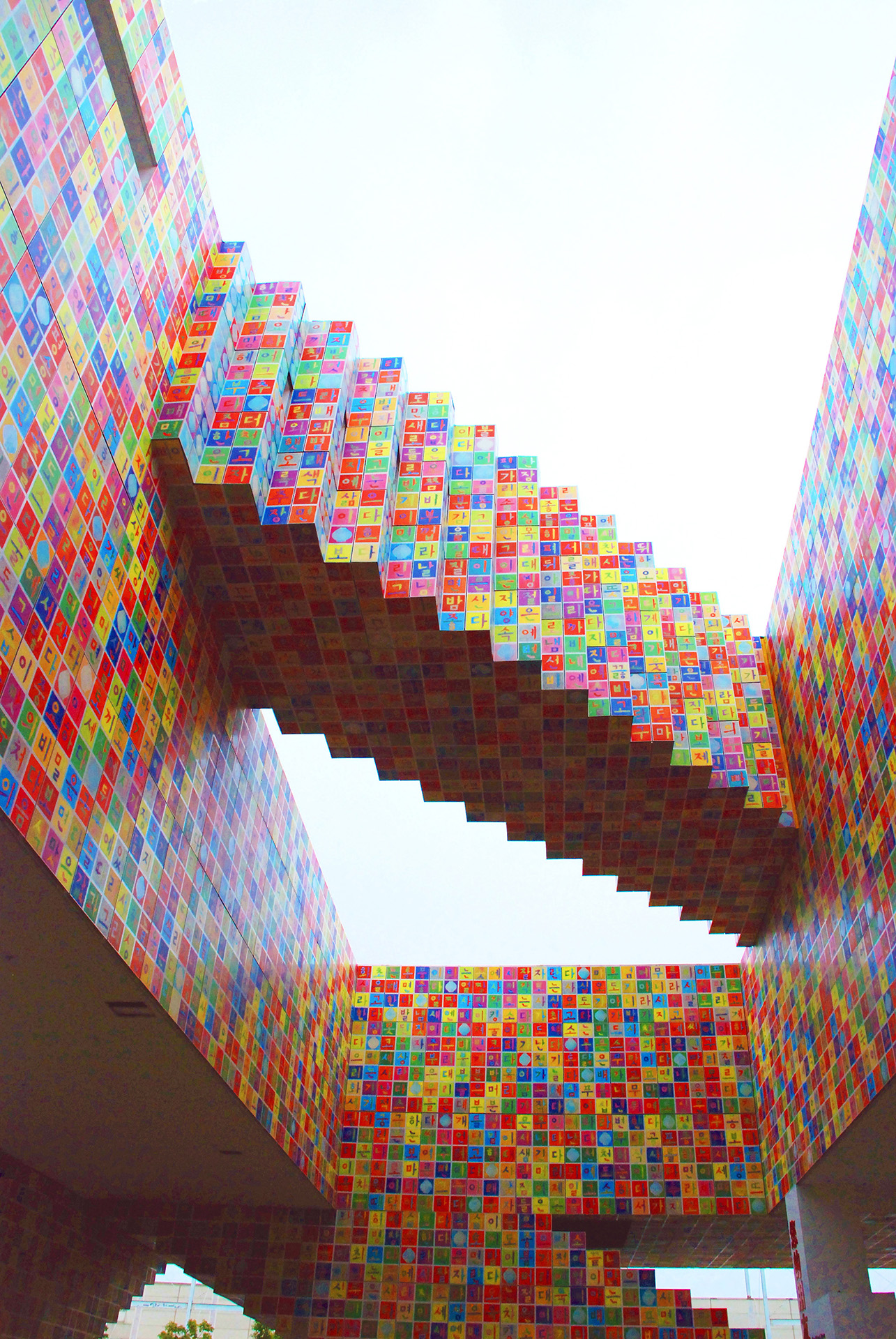

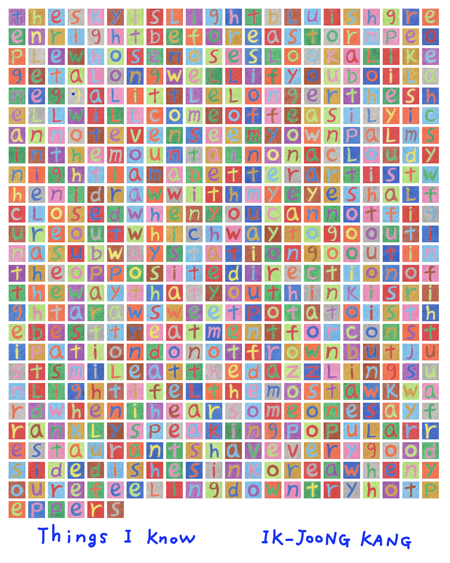

Can you describe your artistic vision for the South Korean Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo 2010? Could you talk a bit about the process involved in building a monumental installation of this scale? How did the theme for the installation Things I Know come about?

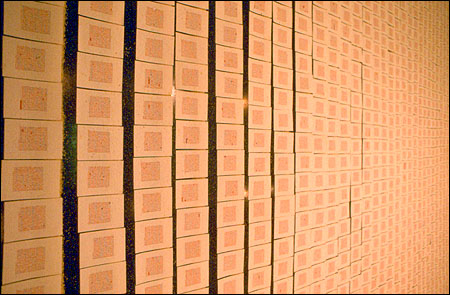

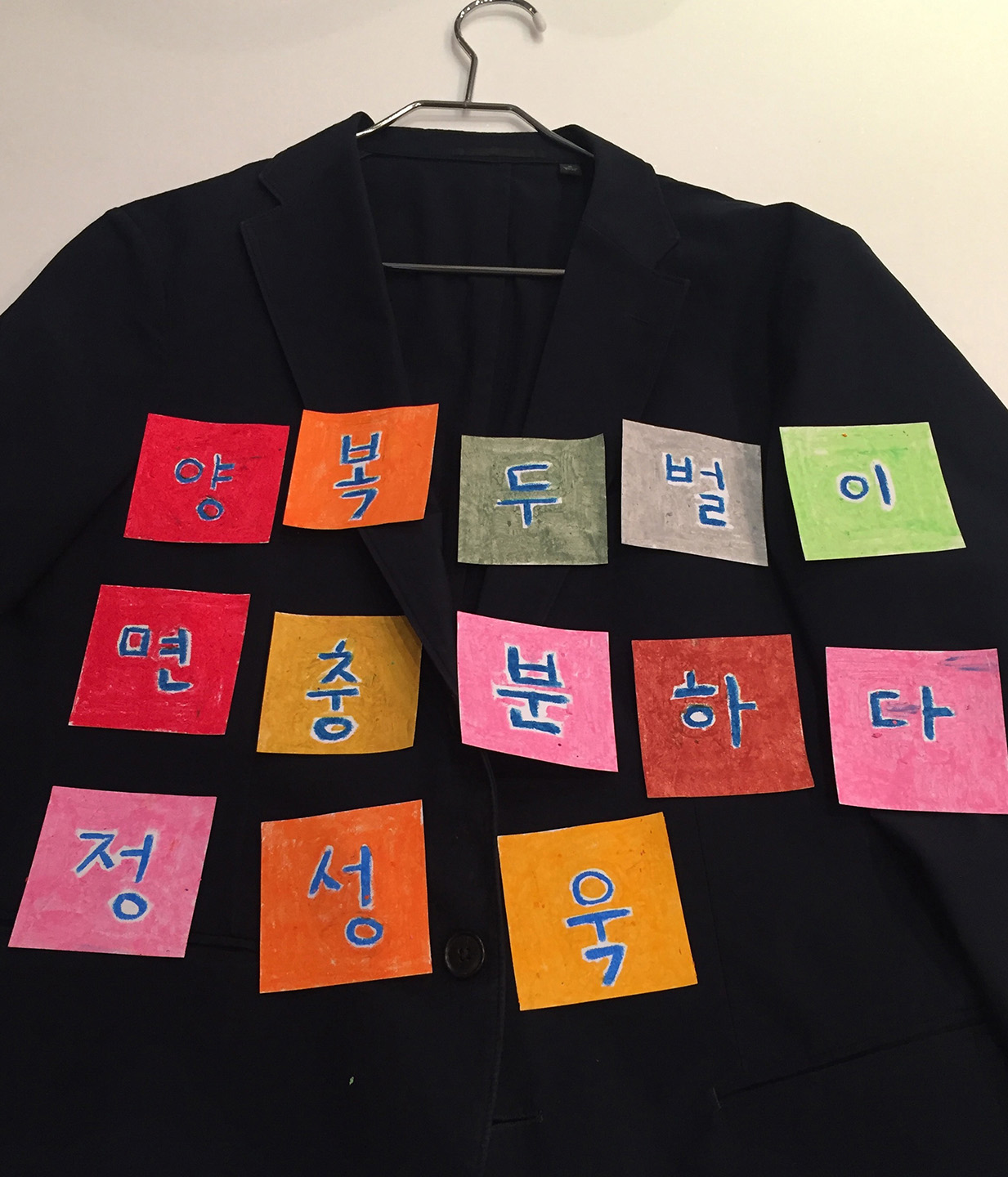

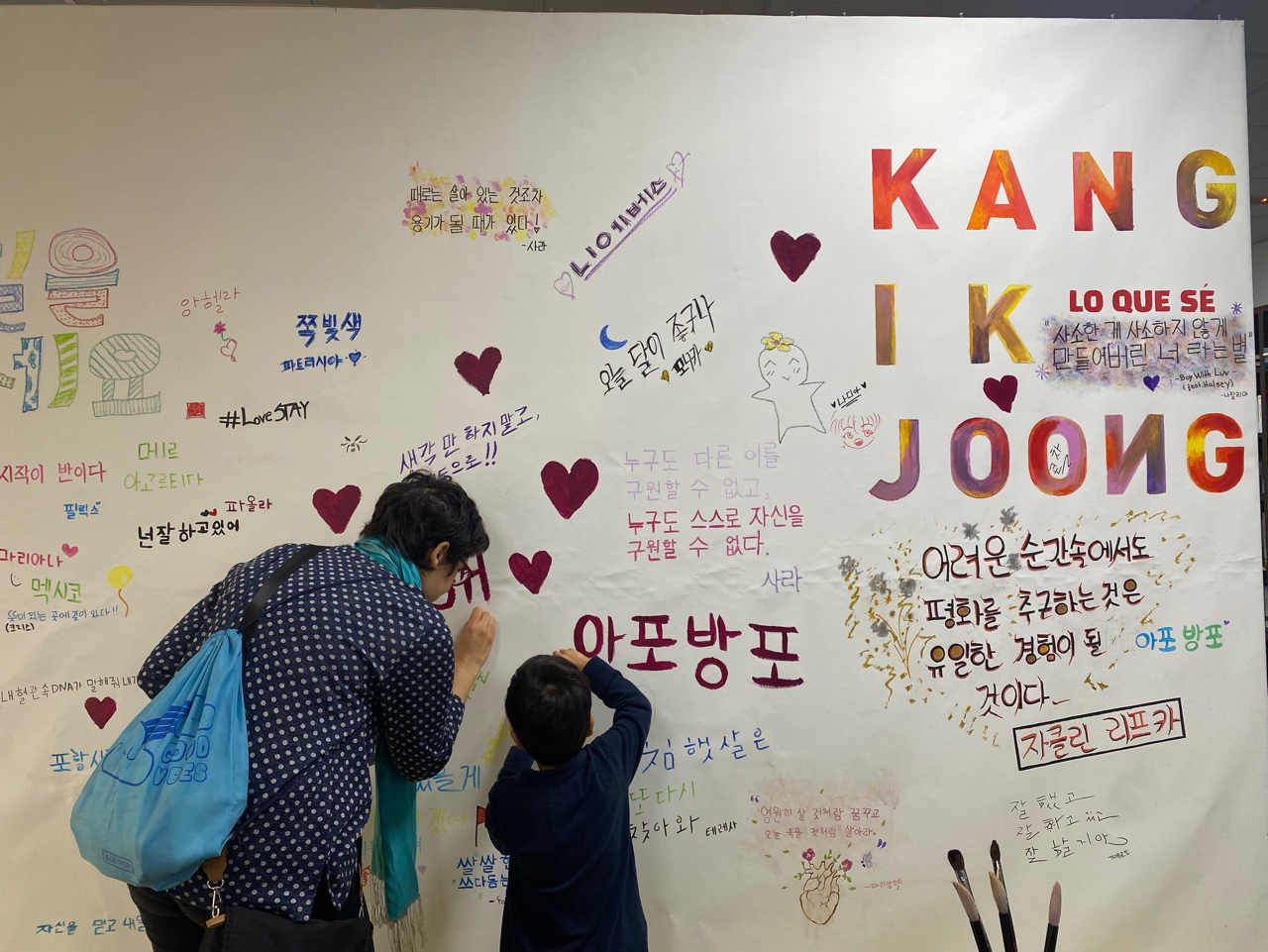

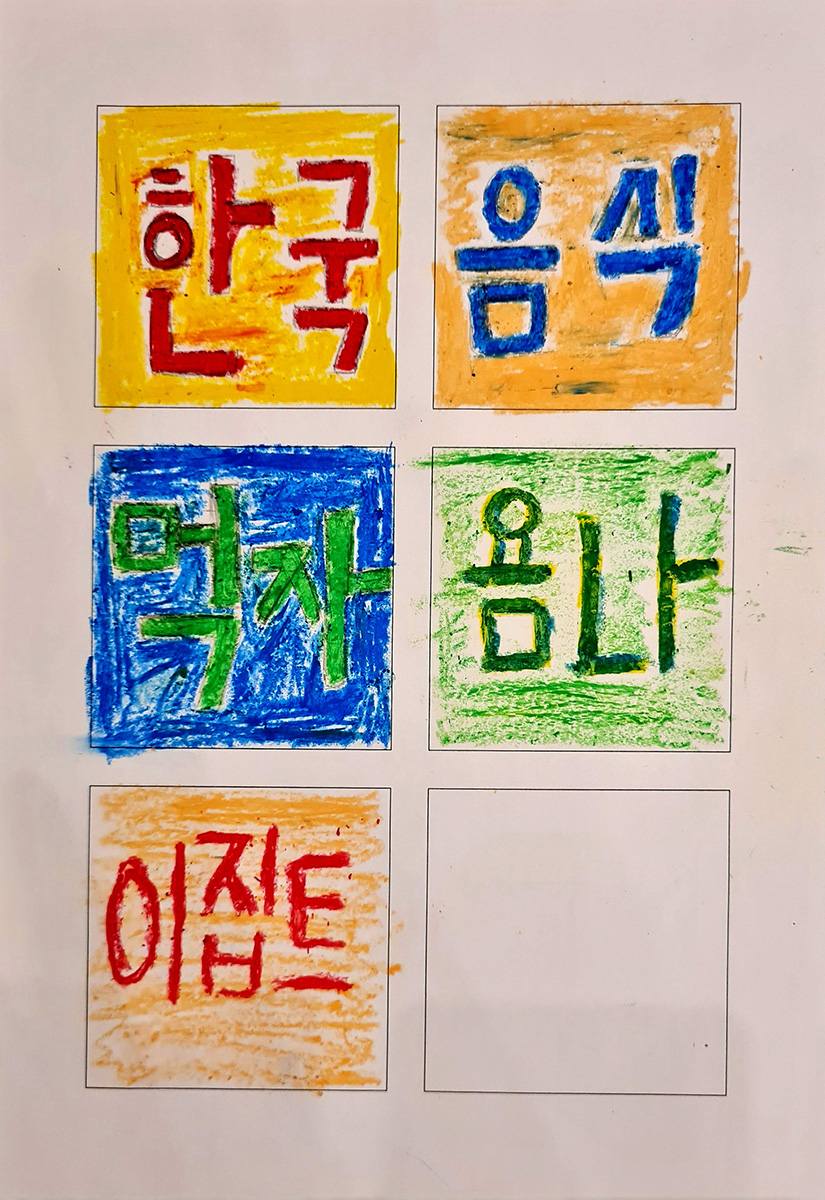

In over a decade, I have written thousands of short sentences in Hangul (Korean alphabet), based on my beliefs and observations of things around me – things that are true or could be true, but there is no scientific proof that they are true. It is a process that I go through to document moments of my life. Things I know is like a personal diary. It is a never-ending process that comes from everyday moments in my life.

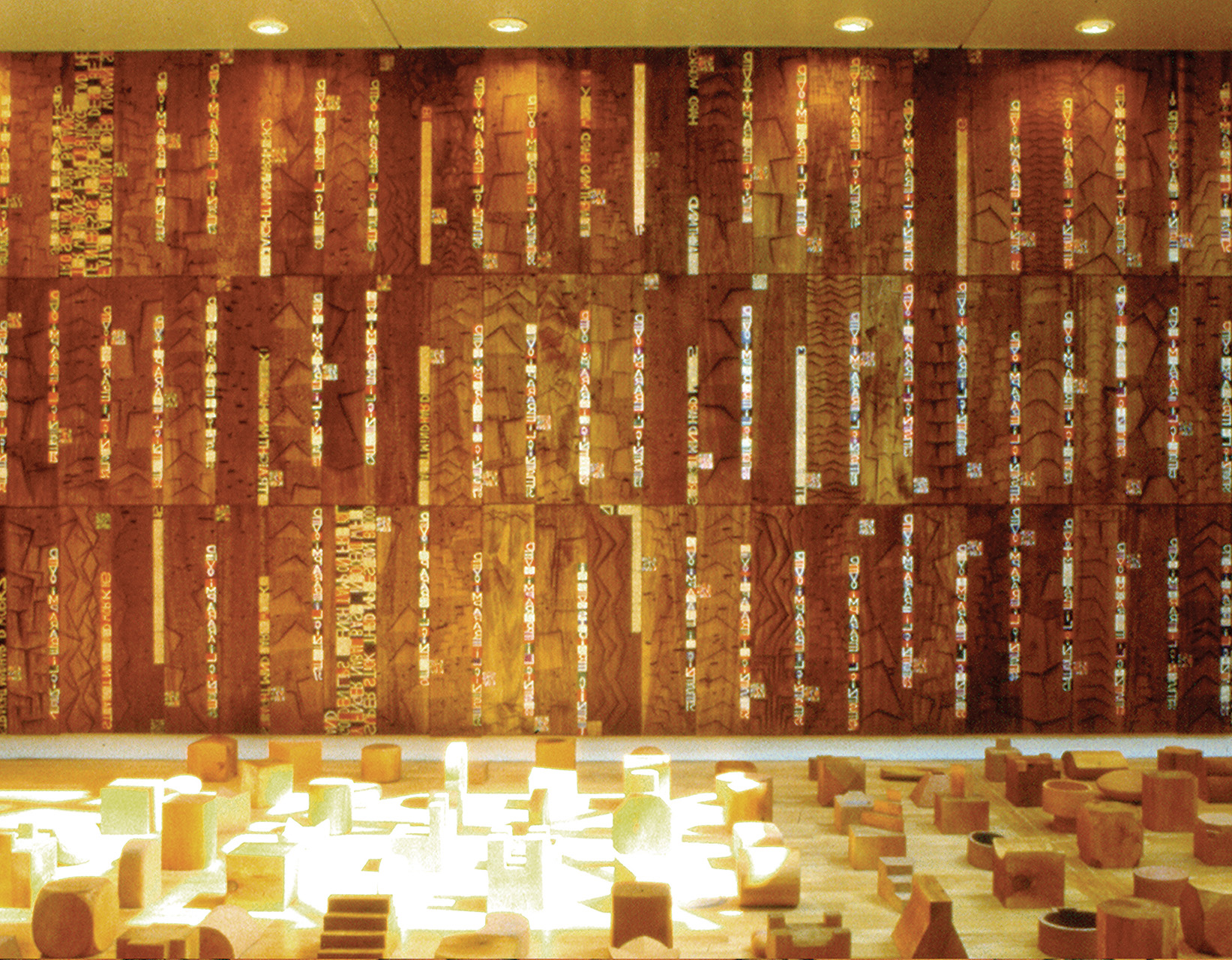

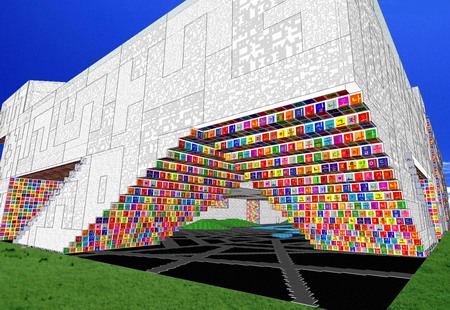

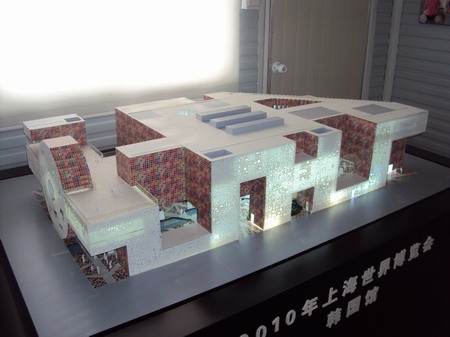

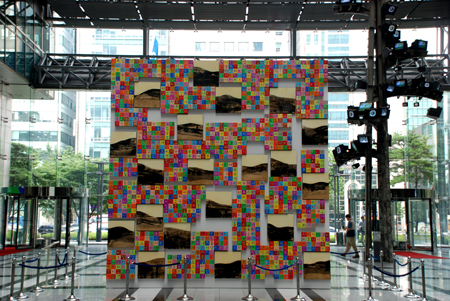

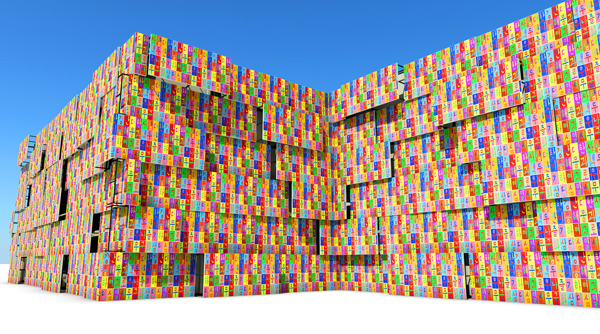

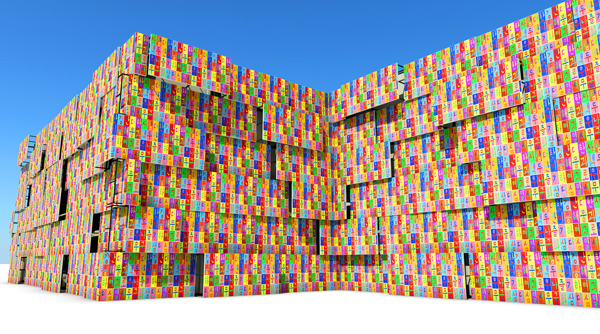

Ik-Joong Kang, “Things I Know”, 2010, Shanghai Expo Korean Pavillion, China. Image courtesy the artist.

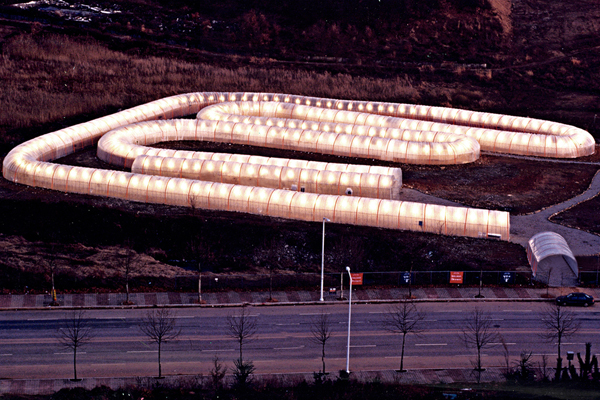

I chose Hangul for the Shanghai Expo 2010 and other projects associated with Things I know. The entire Korean Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo was covered by 40,000 aluminium panels of Hangul. The alphabet has 24 consonant and vowel letters [and] I always thought the moon jar and Hangul share the same secret code of two becoming one. Like the top and bottom part of a moon jar, which become one after waiting in the fire, the vowel and consonant of Hangul make a sound after they are combined in a syllabic block.

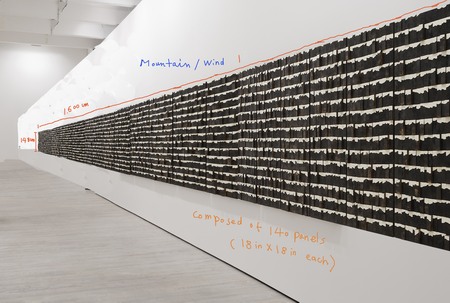

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Mountain and Wind’, 2008-2010, 2611 works on wood, 58 x 58 cm each. Gwanghwa Mun, Seoul, Korea. Photo by Jeong Yul Lee. Image courtesy the artist.

How did you select the works for your retrospective “Ik-Joong Kang vs Ik-Joong Kang” (2011) at Posco Museum of Art in Seoul? What is the meaning behind the title? Can you talk about some of the works that were exhibited?

I believe life is like a train ride in which people are constantly getting on and off. One may stay on for a very short time, but another may stay on for the entire ride. In most of my installations, I share stories of things I know, people I met during my journey on the train of life. A small man sitting on top of the structure with binoculars appears at many recent installations. The small man represents me. I carefully observe the dialogue between people and I collect words and sounds like I catch butterflies in the field. Among the passengers, I find myself sitting, eating, sleeping and talking, but only if I can maintain the distance from another Ik-Joong Kang who sits on top of the train with binoculars.

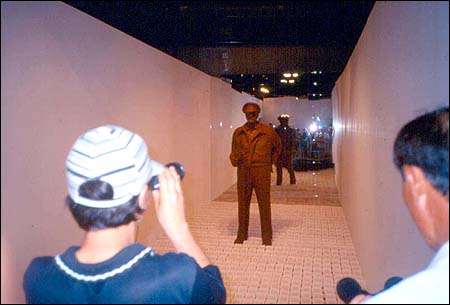

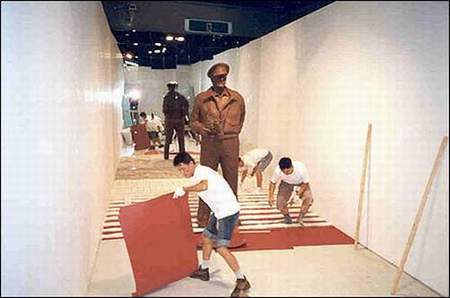

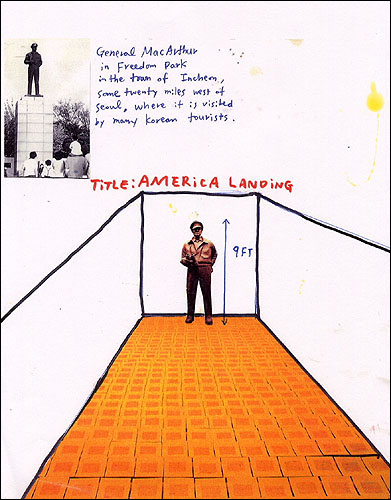

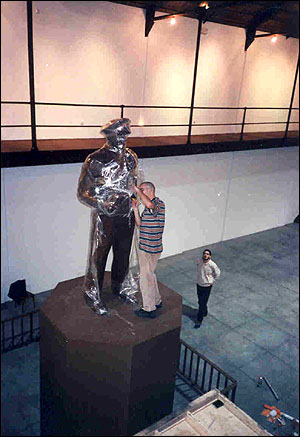

One of the pieces installed at “Ik-Joong Kang vs Ik-Joong Kang” was a nine-foot statue of Korean War hero General Douglas MacArthur entirely coated in chocolate. It came from the exhibition of “8490 Days of Memory” at the Whitney Museum of Arts at Philip Morris in 1997. The sweet scent and taste of creamy chocolate played a role in the recollection of memory. I attended an elementary school near a US army base in the Itaewon district of the city [Seoul]. My friends and I would often ask the GIs passing by in their Jeeps, “Give me gum or give me chocolate.”

Chocolate was an extraordinary treat to us. When I was successful in retrieving a candy bar, I slowly removed the foil wrapper before inhaling the scent of chocolate – “smelling America” – to extend the happy moment. MacArthur, who commanded UN military forces during the Korean War, was responsible for driving North Korean forces back over the 38th parallel. General MacArthur is remembered to be bitter as war and sweet as chocolate by many Koreans, including me.

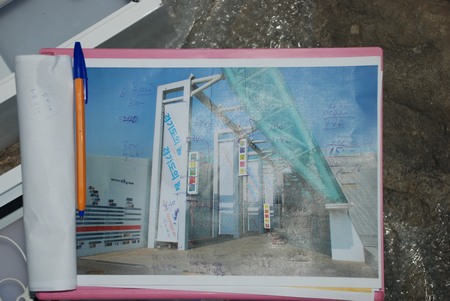

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘The Bridge of Dream’, (‘Things I Know’), Suncheon Bay Garden EXPO 2013. Image courtesy the artist.

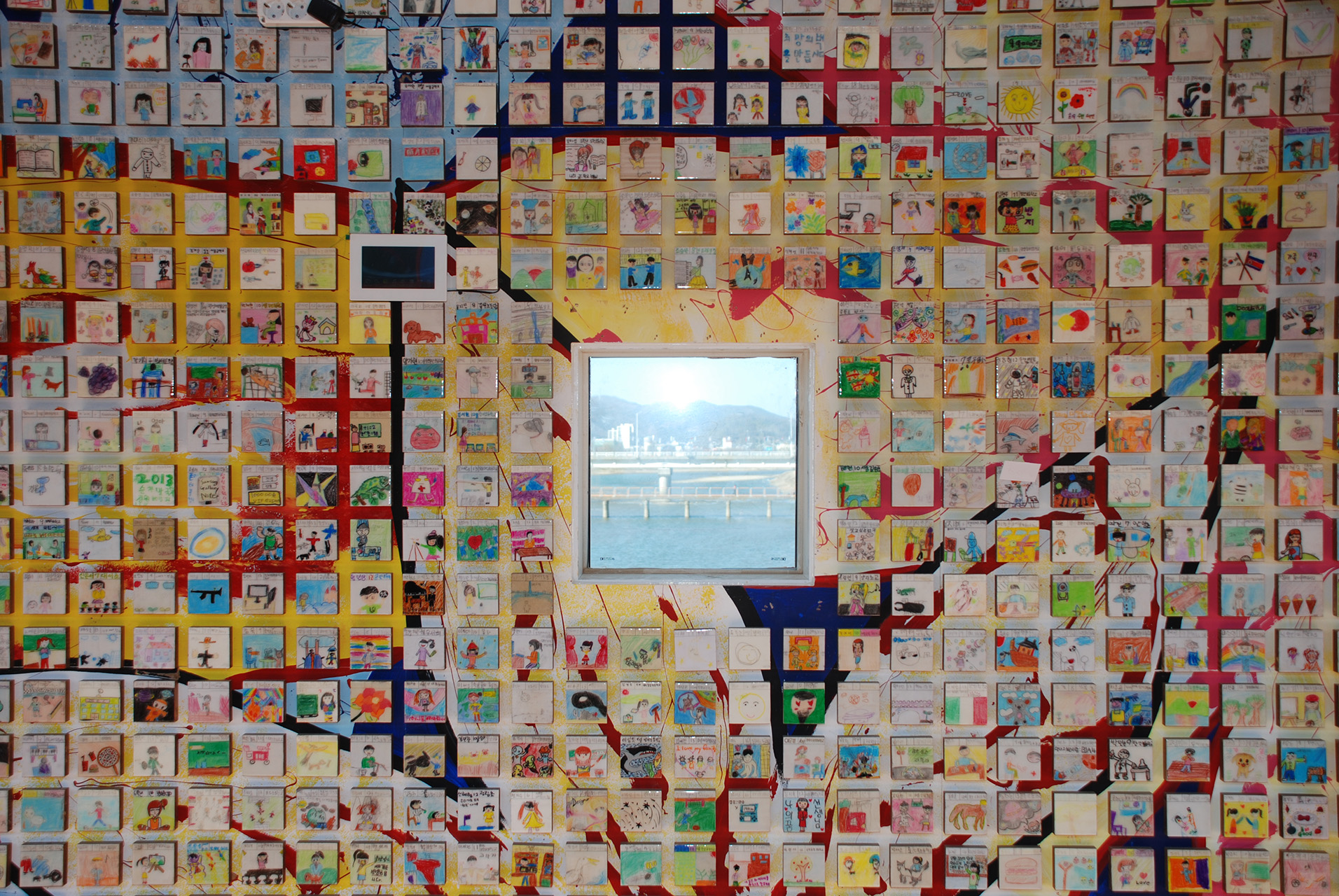

Could you talk about The Bridge of Dream, your recent work for Suncheon Bay Garden EXPO 2013? What was the inspiration behind this work? Many of your recent installations involve participation from children around the world and large group of volunteers. You have previously talked about recruiting volunteers from a prison for a project. Could you talk about the community aspect of your work?

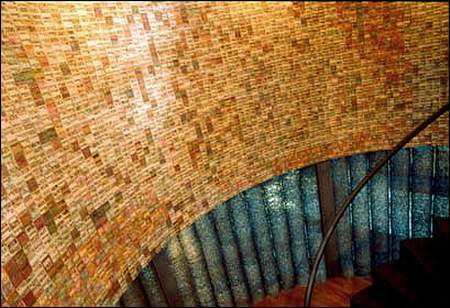

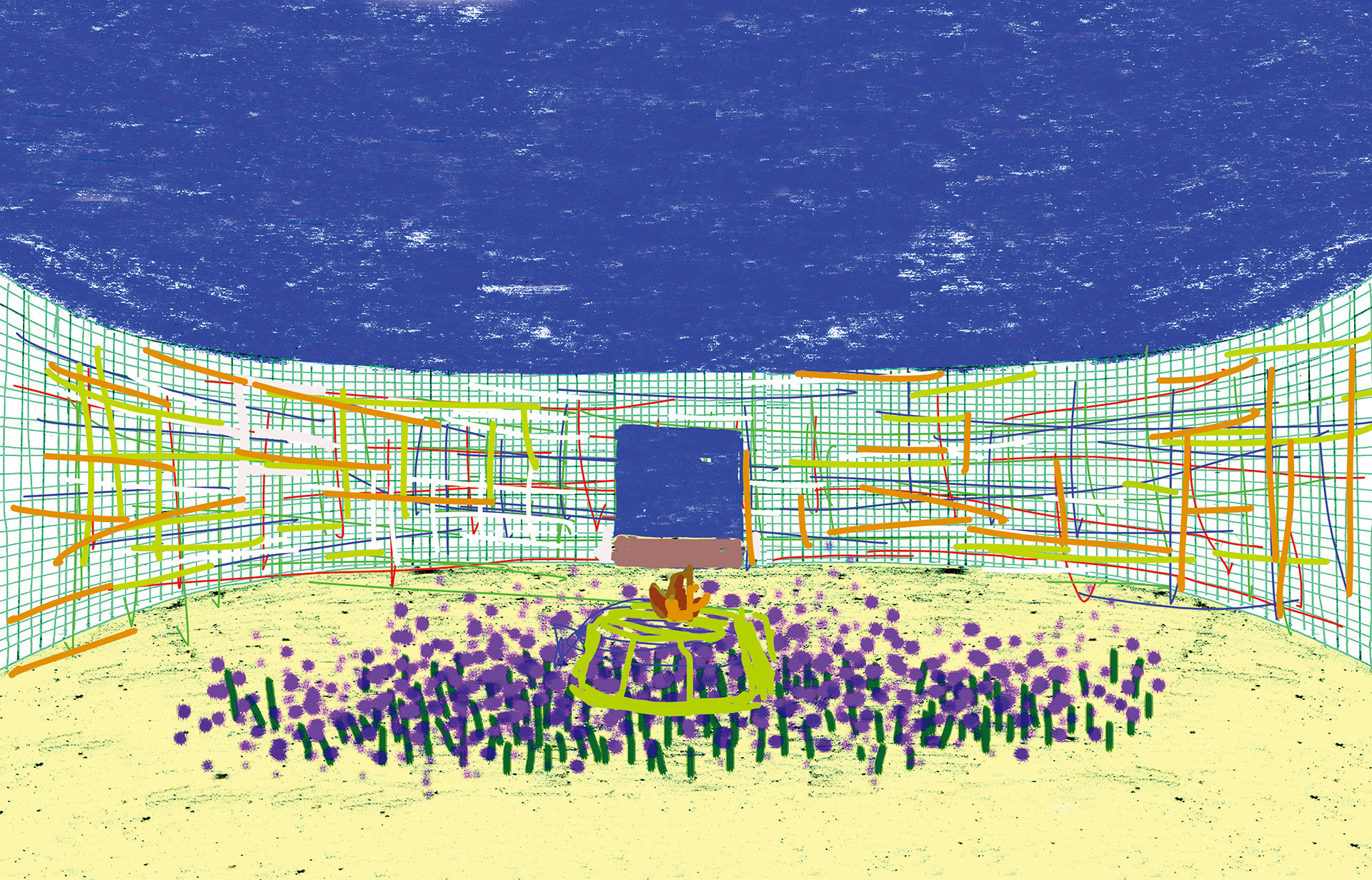

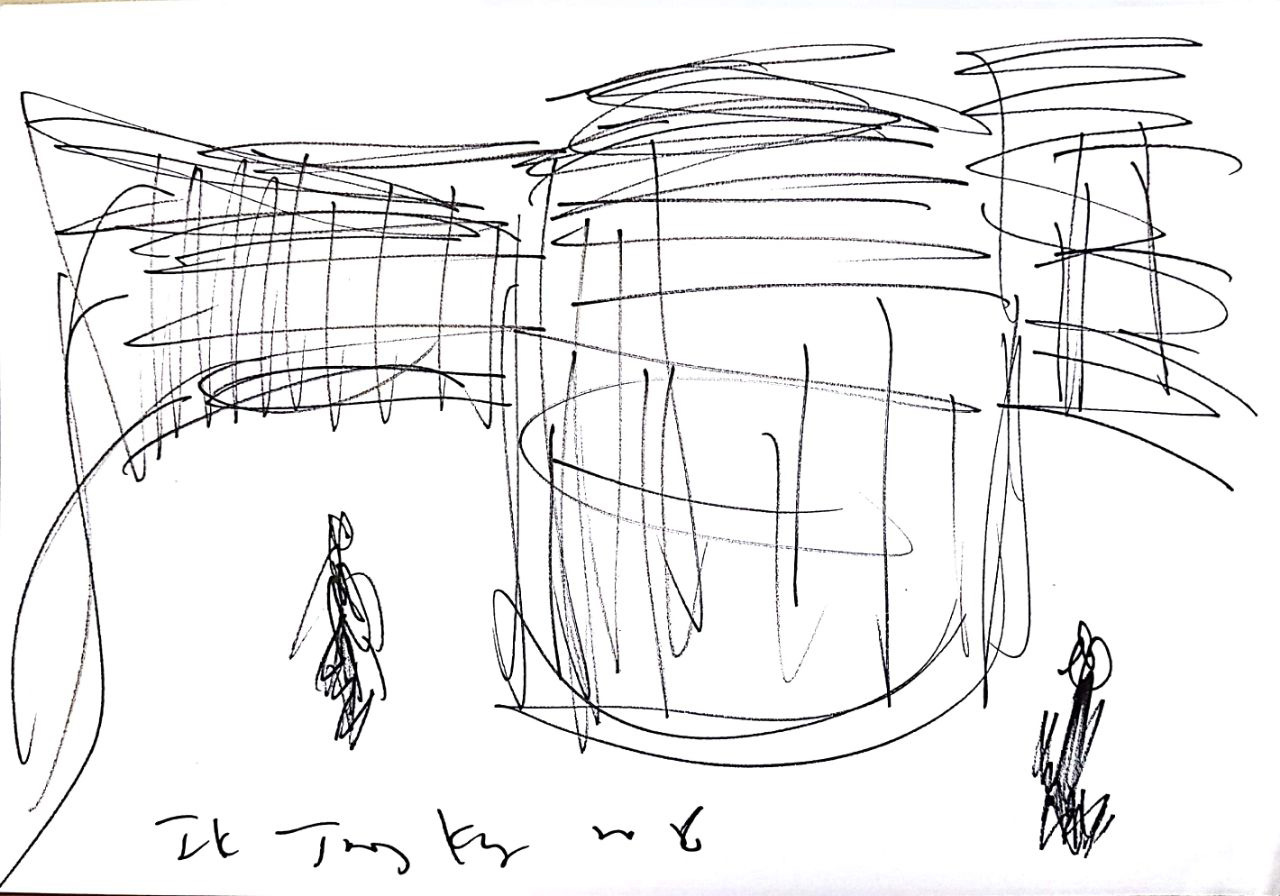

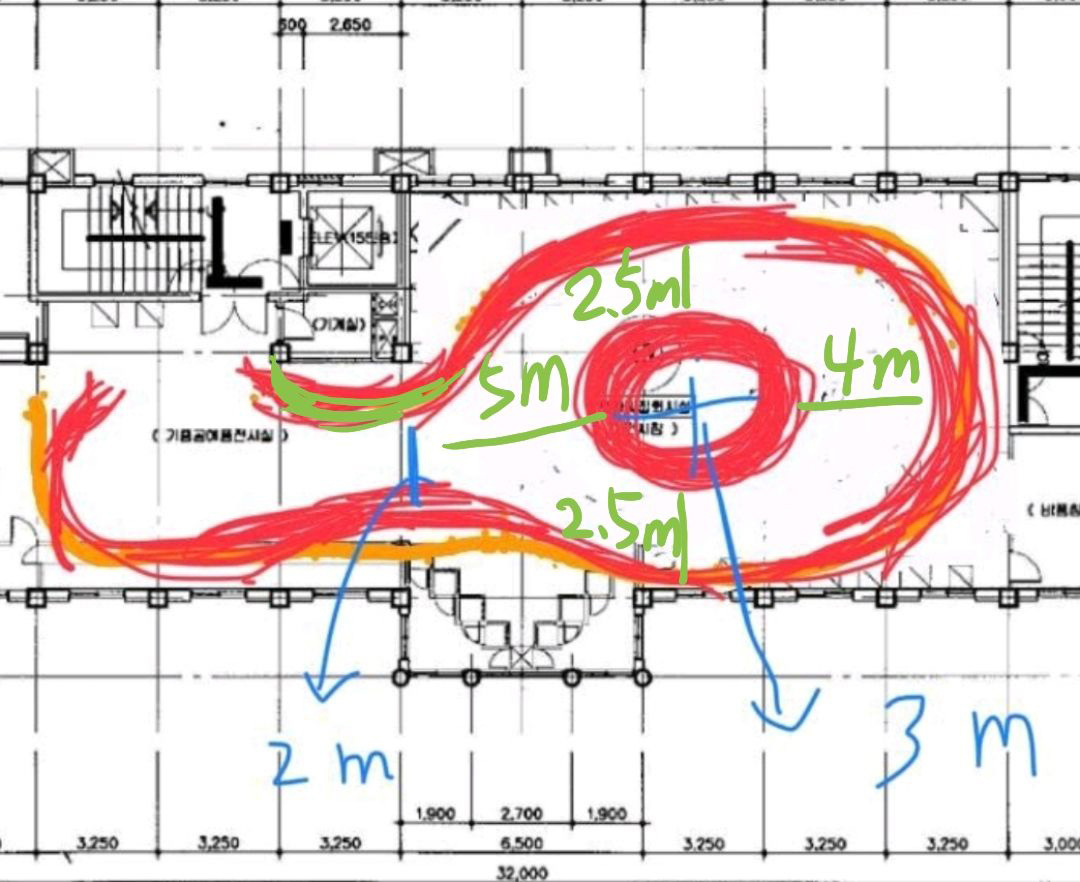

The Bridge of Dream was constructed above the water in the form of a 175-metre-long bridge which connects the east and the west of Suncheon city. It was made to model a future project, The Bridge of Dream, which would connect the two Koreas over the Imjin River. Like the way John A. Roebling built a smaller suspension bridge over the Ohio River before he made his masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge.

On the exterior of the bridge I displayed Things I know. It goes like this [from a poem by the artist]:

People whose noses are alike get along well, Do not frown, but just smile at the dazzling sun light. Even a rabbit in good mood makes a sound. Dogs take after their owners. We have a stage phobia when we try to show more than what we are.

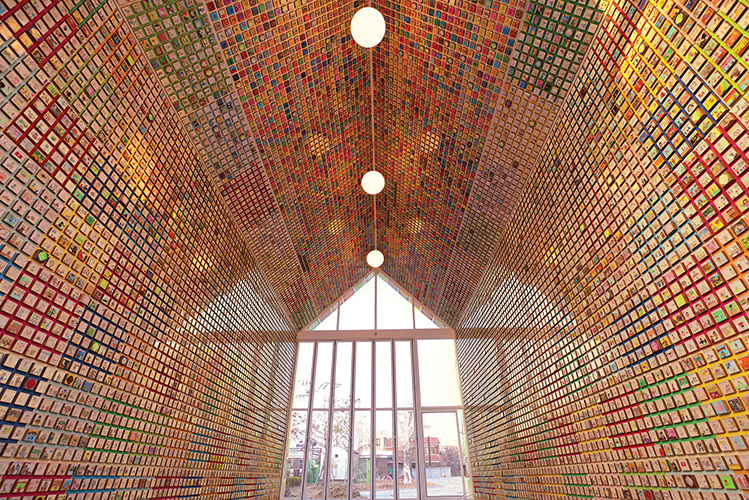

The interior of the bridge holds approximately 145,000 children’s drawings (each three by three inches) entitled My Dream by children from sixteen different countries. The children’s dreams fill the inside of the bridge and anyone who walks on this bridge will be sent to the future without even having to buy a ticket. The exhibition was closed after a six-month run, drawing over four million visitors. Now the bridge is open permanently.

Your works have involved painting, installation, sculpture and sound. Is there a medium that you would like to explore further?

People. I’d like to explore more about collaboration with people. People will be my main medium and my main inspiration for exploration.

Since 1999 we have created over thirty different installations of children’s drawing in hospitals, libraries, museums, schools and outdoor in places such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Jordan, Germany, Korea and other countries. Over 10,000 volunteers and nearly 1,000,000 children around the world made these projects possible. Children from over 150 countries and volunteers had helped all the projects possible including prisoners, nursing home residents, soldiers and homeless people. People are the main source of our timeless dialogues.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Eighty-Four Wishes’, 2008 and 2013, Seoul Museum of Art. Collection of Seoul Museum of Art. Photo by Jeong-Yul Lee. Image courtesy the artist.

Upcoming projects

Are there any new projects you are working on?

I just finished the installation called Eighty-Four Wishes in the lobby of Seoul Museum of Art, featuring 84 moon jar paintings.

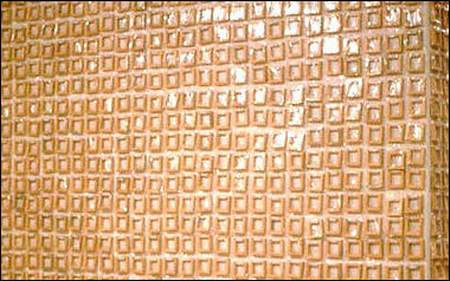

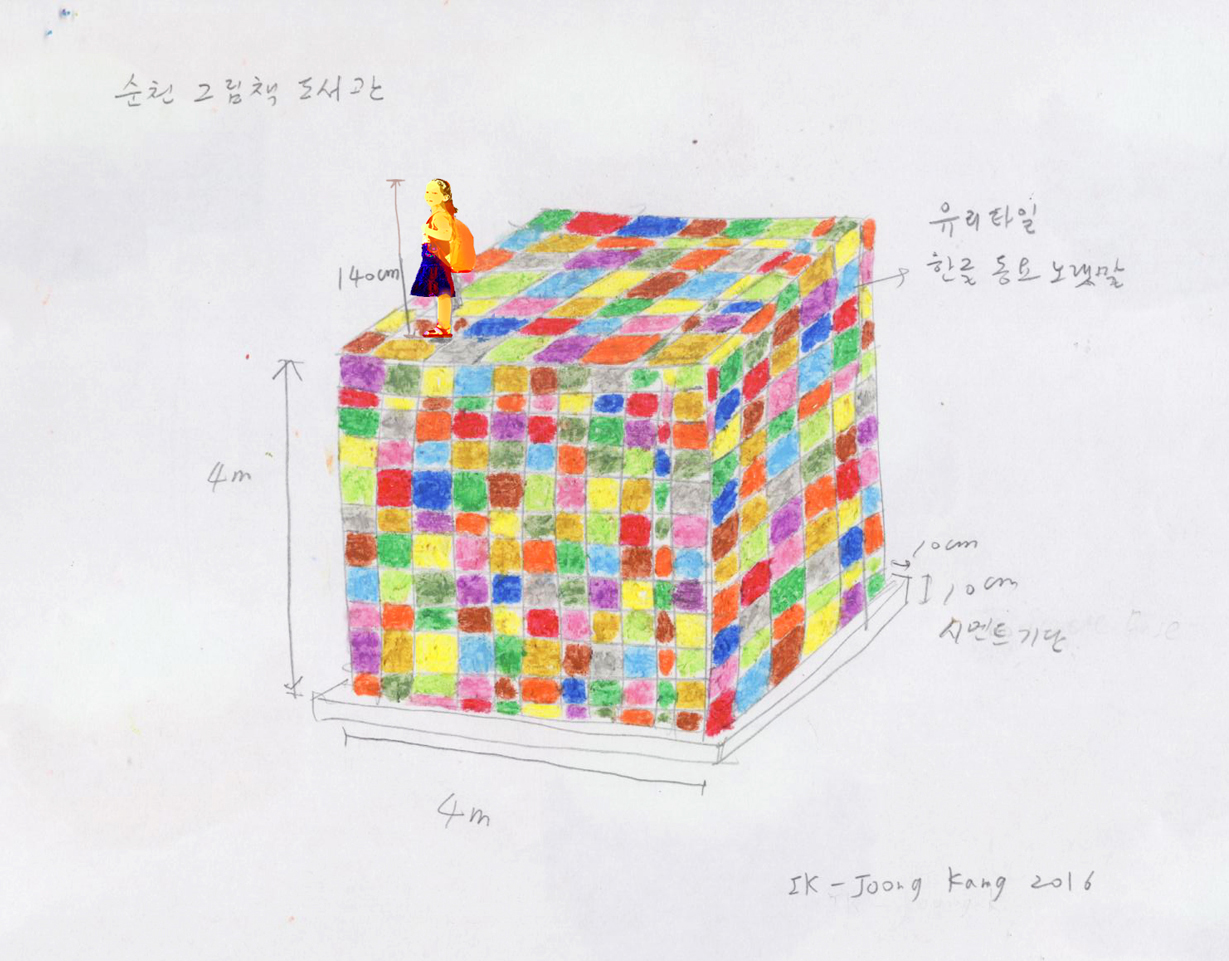

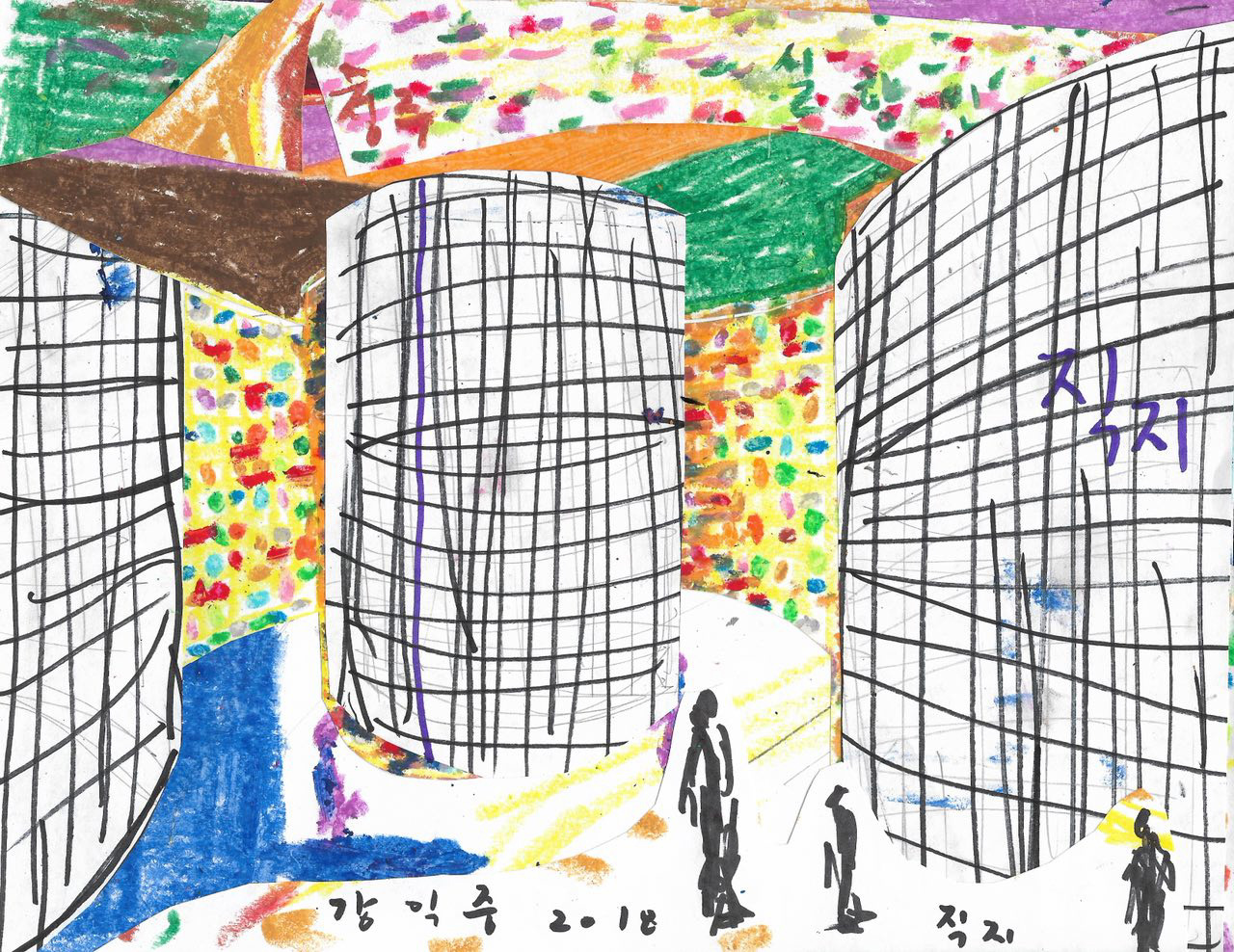

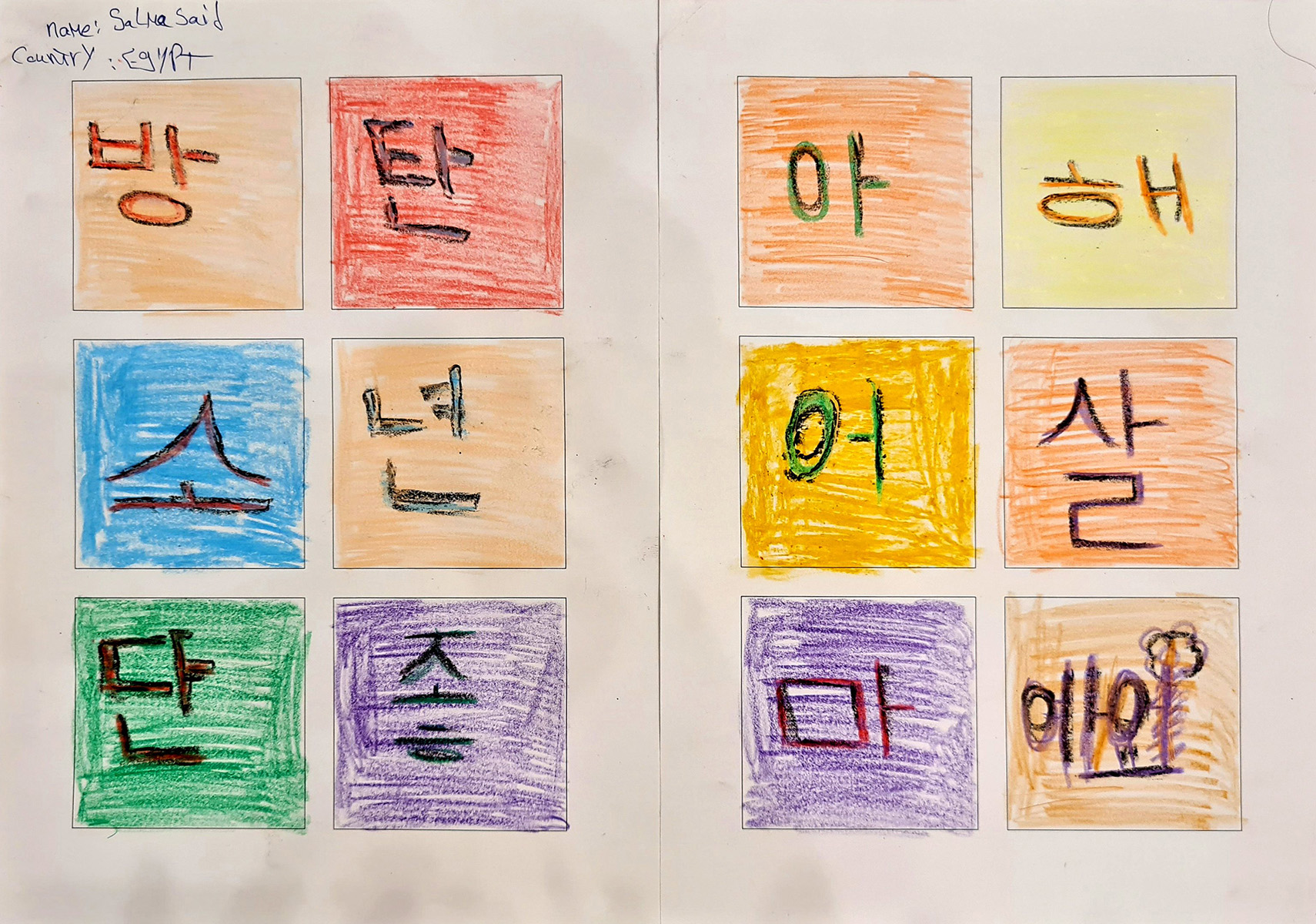

Currently, I’m working on an architectural project, Things We Know, in Cheongju, my hometown, covering the entire former cigarette factory with the Hangul [script]. This is a community project where I will ask 20,000 Cheongju citizens things they believe in and then transfer their beliefs onto coloured glass tiles.

Next fall, the entrance of the newly renovated Queens Museum of Art will be covered with the artwork Things I know and 3,000 drawings from children in New York will be installed inside the Museum library.

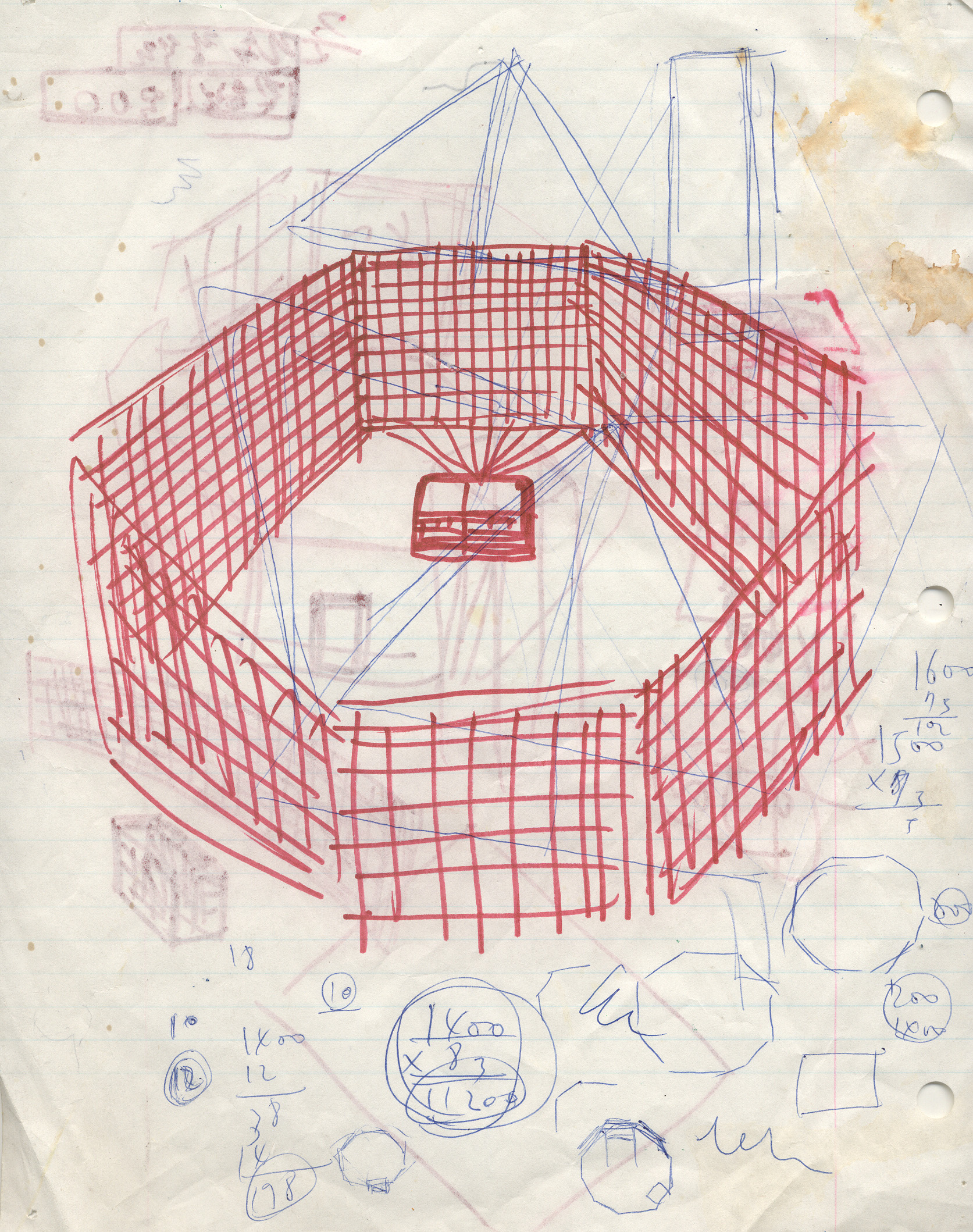

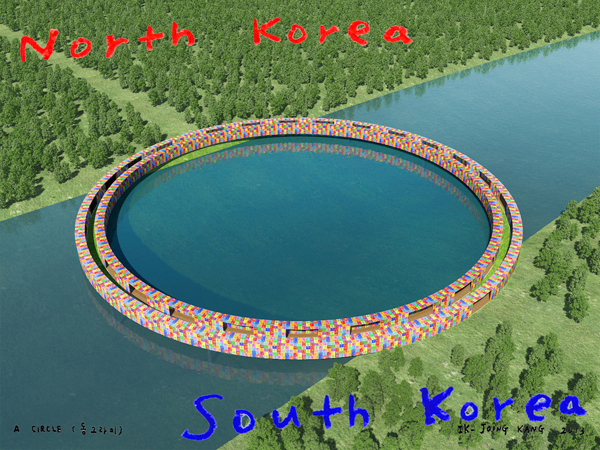

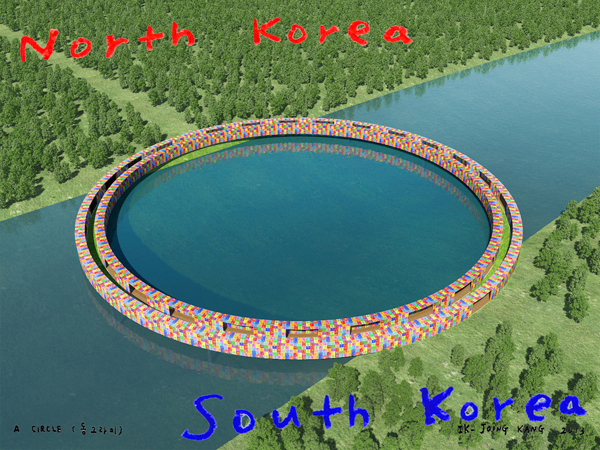

As a future project, DongG Ra Mee (a Circle), which is the plan for the bridge over the Imjin River, is going to be presented for the first time at the 2014 Venice Biennale [International Architecture Exhibition] this spring. This time I’m representing South Korea as an architect, not as a painter.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Things I know’, 2014, former cigarette company, Chungjoo, Korea. Image courtesy the artist.

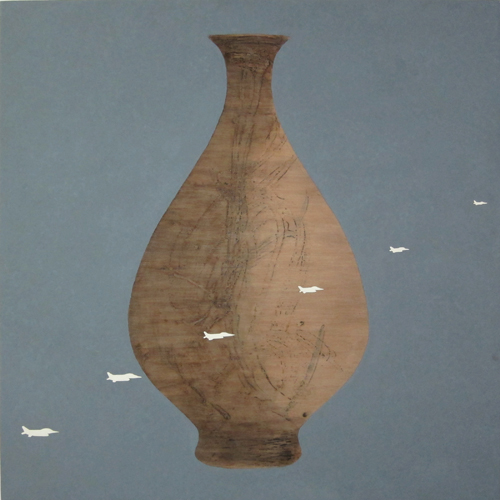

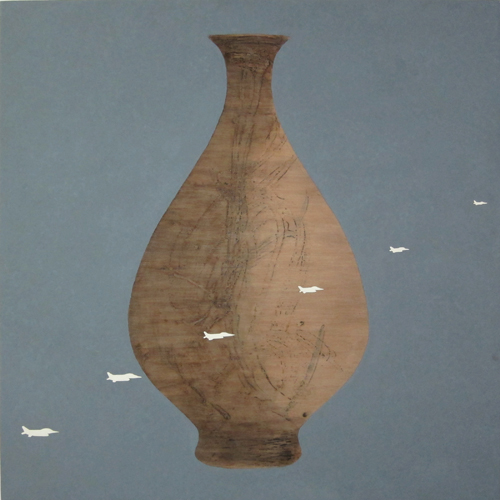

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Buncheong Airplanes’, 2013, 47 x 47 in. Image courtesy the artist.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Mountain and Wind’, 2010, 8000 works on wood, 380 x 1140 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Blue Moon Jar’, 2012, 72 x 72 in. Image courtesy the artist.

Ik-Joong Kang, ‘Dong-G-Ra-Mee (a Circle)’, 2013-2014, proposal, 180 metre diameter, Imjin River, Korea. Image courtesy the artist.